Lunch Hour Lectures: The handmaiden’s emissions – international shipping in changing climates

By Thomas Hughes, on 28 January 2016

“This lecture on the handmaiden’s emissions is not actually about the flatulence of household servants,” Dr Tristan Smith (UCL Energy Institute) joked at the Lunch Hour Lecture on 26 January. The “handmaiden” is in fact the affectionate nickname used for the world’s shipping – so called because it is globalisation’s servant, without which we wouldn’t have the same food, commodities or fuel.

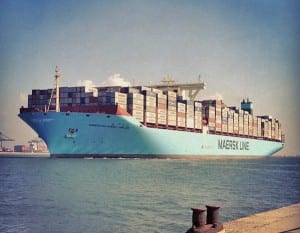

Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller, credit: Maersk Line.

However, it has a huge environmental cost in CO2 emissions that has continued to grow as GDP and demand has risen. Dr Smith has been working with the team in the UCL Energy Institute to help find solutions to cut emissions, while keeping costs low.

An average container ship has around 1,500 containers on it, with each container the size to be pulled by a single lorry. There are thousands of these ships, which in total account for about 2-3% of global emissions.

With the Paris Agreement in December 2015, we have a new ambitious goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, which would mean a goal of dropping the intensity of shipping emissions by 60-90% over the next 30 years.

There will be some drop in shipping as the amount of oil, coal and gas tankers required goes down; however, this is likely to be offset by the continued growth of the international market, which will drive a greater demand for container ships and food. So what can we do to bring down emissions?

The technology to help bring down emissions from the shipping fleets is already available and has begun trials. Solutions include using wind in various forms to decrease the fuel requirements, or using ships run entirely off of hydrogen fuels or batteries.

Some of these solutions have their own problems – for example creating hydrogen fuel or electricity for batteries can potentially create a lot of CO2 emissions, but these are problems that can be solved.

Most ships have approximately 30-year lives and financing for 7-12 years. This would mean that these ships would have to be planned and built soon if we are to meet the goal of not exceeding 1.5°C of warming. However, the main roadblock to this goal is reaching an international agreement to combat shipping emissions.

The third largest shipping fleet in the world is registered under the flag of the Marshall Islands. The Marshall Islanders have a vested interest in keeping emissions down, as anything above a 1.5°C rise is likely to be a death sentence for the group of islands in Micronesia – where on average the land is only 2m above sea level.

They are a clear example of the difficult balance to be struck between countries that rely on the shipping industry for their economy, and are likely to be against any rising costs, and the drive to reduce CO2 emissions.

When these ships are out on the “High Seas”, as they are still called, they are outside the jurisdiction of any countries laws, therefore, they carry a chosen countries’ laws with them by flying that countries flags.

These laws are decided by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), which reaches all decisions by consensus. However, when there is a conflict over reducing shipping emissions and keeping costs down, reaching a consensus can be very difficult.

“So surely it would be better for some countries to unilaterally take action to cut emissions?” a member of the audience asked. The problem, Dr Smith said, is that this would simply cause shipping companies to change their registered country to avoid any costly regulations, also known as taking a “flag of convenience”.

The best hope, Dr Smith maintained, was that the IMO countries could reach a consensus, and there is a lot of pressure since the Paris Agreement for them to do so. It is essential that the handmaiden can learn to adapt to the changing demands of the global economies.

Close

Close