Danny Boyle’s Sunshine: the science behind the fiction

By Ben Stevens H P Stevens, on 12 November 2014

From Georges Méliès to Tarkovsky and Kubrick, the wonders of space have taken a special hold on the imaginations of some of the world’s most visionary film directors.

UCL’s very own Christopher Nolan (UCL English, 1991) is the latest to offer his response with the hugely anticipated Interstellar, which opened on Friday.

Before him, Danny Boyle gave us his own epic vision in Sunshine (2007) – which was shown at a special screening organised by the UCL Public and Cultural Engagement (PACE) team at the Stratford Picturehouse in east London on 28 October.

The film, starring Cillian Murphy, follows the crew of the Icarus II as they attempt to reignite our dying Sun with a specially designed nuclear weapon that must be delivered directly into its core, if life on Earth is to survive.

Before the screening, visitors had the chance to view the space-themed objects from UCL’s museum collections, including a meteorite, part of a crashed satellite and some historical NASA images of space.

Jamie Ryan, a PhD research student in the Solar Group at UCL’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory (MSSL), then put the film in context with an introductory talk that provided the audience with a crash course in solar science.

Bad physics

He began by pointing out that although Professor Brian Cox (yes, the Brian Cox) was scientific advisor on the film, it still contains a number of mistakes when it comes to the physics shown on screen.

Generously, he conceded that Cox and Boyle were probably aware of most of these mistakes, but realised that the film would be more atmospheric if they left them in – such as hearing sound in the vacuum of space.

Throughout Sunshine, the Sun is shown as a staggeringly beautiful ball of golden fire – yet I was surprised to learn that this was also one of the ‘mistakes’ that the production team chose to leave in.

In reality, “The Sun would look quite boring to our eyes,” Jamie pointed out. Thanks to the protection that our atmosphere gives us from harmful radiation, the human eye has evolved to see only a very slim spectrum of light, making most of the Sun’s processes invisible to us.

So, to look at it in all its glory, we need to get out of Earth’s atmosphere. As Jamie explained, MSSL has played a major role in many space science missions designed to do just that – including Hinode and SOHO, both of which are currently in space.

The next major one is Solar Orbiter, which is due to launch in 2017, and will be the first spacecraft to get so close to the Sun (0.28 astronomical units).

The solar wind

On board, there will be a number of instruments including the Solar Wind Analyser, which contains sensors designed and built at MSSL. It will measure the density, speed and temperature of the particles (electrons, protons and ions) in the solar wind.

In order to explain what the solar wind is, Jamie gave us a quick overview of the processes that take place within the Sun, beginning with the astonishing fact that “every 1.5 millionths of a second, the Sun releases more energy than all humans consume in an entire year. Without it, there would be no light, no warmth and no life”.

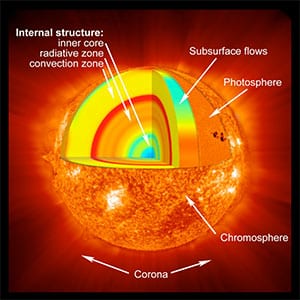

The sheer density at its core means that hydrogen atoms collide with enough force that they literally meld into a new element – helium. This process – called nuclear fusion – releases energy in a chain reaction that allows it to occur over and over again.

This energy travels outward through the Sun, taking 170,000 years to reach the photosphere, where it is emitted as heat, charged particles and light.

Those charged particles (high energy protons and electrons) travel at a sufficiently high speed to escape the Sun’s gravitational pull, creating a ‘solar wind’ that moves all the way to the edge of the solar system and “pushes against the fabric of interstellar space billions of miles away”.

In effect, “On Earth, we are basically living in the Sun’s atmosphere,” he added – even though, “compared to Earth’s atmosphere, the Sun’s is very sparse and very hard to see”.

East London expertise

Again, Sunshine takes rather a lot of artistic licence with its depiction of the solar wind. Yet for all its scientific inaccuracy, it is a dazzling film. Some people find its change of narrative gear in the final third to be too jarring, but seeing it for a second time, I was once again swept along by Boyle’s confident direction.

Even seven years on, its sound and visual design are stunning – a tribute to the fact that it was, according to the credits, “proudly made in the East End of London at Three Mills Studios”.

And it is this kind of local creative and technical expertise that UCL will hope to connect with when the university opens its new campus on the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

Close

Close