The Ancient Olympics

By news editor, on 25 June 2012

![]() Annette Mitchell, UCL Greek & Latin PhD student

Annette Mitchell, UCL Greek & Latin PhD student

The first Olympic Games are thought to have occurred in 776 BCE. It was held at Olympia in honour of Zeus and was the first in a series of four Panhellenic games.

first in a series of four Panhellenic games.

These Panhellenic games, held in honour of other Gods, also consisted of the Pythian, Nemean and Isthmian Games, and were attended by delegates from the various Greek city-states. The last Olympics occurred in 394 CE in order to supress paganism in favour of Christianity.

The ancient roots of this now modernised global event are often forgotten and Professor Chris Carey of the UCL Greek and Latin Department has organised a series of events – listed on the Roman Society website – in the run up to the London 2012 Olympics to jog our ‘memory’.

These events focus on various aspects relating to the ancient Greek roots of the games. These include ancient ideas regarding anatomical ideals and the ideology of victory, and modern aspects such as the revival of the games in Athens in 1896.

‘Olympic Angles’ was the title of the latest event in this series and consisted of four short talks of 10 minutes covering aspects of the ancient Olympics that are pertinent today. Paul Cartledge, Professor of Greek History at the University of Cambridge, hosted the panel. It was followed by 40 minutes of audience questions.

Star events

Mark Golden, Professor of Classics at the University of Winnipeg, spoke first, asking what the favourite sport of the ancient Greeks was – wrestling or the stadion (running race)?

Arguments in favour of the stadion include that the highest amount of money was awarded for victory in it, as well as the term stadium being derived from this race.

Arguments in favour of wrestling include that it was more often depicted on ancient Greek vases and more stories survive about it. Ultimately, we do not know and the audience was left to decide based on the arguments.

Cheats never prosper?

Dr Margaret Mountford, of The Apprentice fame, then discussed cheating. She started by relating a myth explaining the origin of the Olympics.

King Oenomaus had declared that no one could marry his daughter Hippodamia unless the suitor beat him in a chariot race. Many had tried and failed until Pelops won the race by cheating.

With the help of the goddess Demeter, Pelops exchanged the lynch pins of the King’s chariot for wax ones. During the race, the pins melted and Oenomaus died. Pelops then married Hippodamia and held the first Olympic Games in commemoration of his wife’s dead father.

This foundation myth implies that the ancient Greeks endorsed cheating. This, however, may not be the case; the aspect of trickery and cunning is perhaps the aspirational ideal preserved in this myth – trickery being much admired in ancient Greece.

This highlights the importance of the investigation of themes such as cheating, which we perhaps think are historically unchanging, but which need to be culturally contextualised.

The sensual allure of the discus

Professor Edith Hall of King’s College London then discussed the beauty of the discobolus (the discus thrower).

The discus was part of the pentathlon, the competition of five events, that consisted of long jump, javelin, discus, foot race and wrestling. The discus thrower was an ancient ideal as he was perfectly toned due to his training in such varied events.

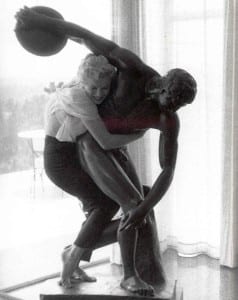

In the modern era, the discobolus is also idealised and has inspired artists such as Van Gough. Discobolus was used by the Nazis as an image of their Aryan ideal, and even Marilyn Monroe was captivated by him as the picture shows.

Professor Hall highlighted differences in how we adopt him, demonstrating the importance of cultural relativism when looking at ancient objects.

Sweat, blood and flies: the real ancient Olympics

Lastly, Professor Michael Scott of the University of Cambridge considered the conditions endured by people attending the ancient Olympics. More than 40,000 people would have gathered in 35-40 degrees heat for 5-7 days. There would have been huge crowds – one year it was so crowded that even Plato found it difficult to find a tent.

Of course today there are still crowding problems, but issues concerning sewage, disease and cleanliness are not as problematic for us. These problems were so prevalent in ancient Greece that attendees thought the best way to punish a slave was to send him to the Olympics!

After the four talks, audience participation covered aspects such as the economic impact of the games and how women were prevented from attending.

The most interesting post-panel discussion focused on the different ideology surrounding the meaning of being an athlete. Ancient Greek athletes wanted to win. They were ruthless and no value was attached to competing or personal bests.

Today, the Olympics represent global peace and union in an unsettled time. The Greeks did enact a truce so the competitors could peacefully travel to the games but once there, victory counted.

Our more peaceful ideology of competition indicates another difference from our ancestors, in the context of the now shared Olympics.

Close

Close