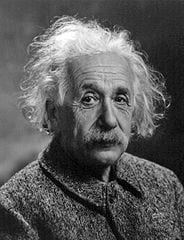

The Search for Genius: Einstein’s Brain

By news editor, on 15 March 2012

Dr Mark Lythgoe (UCL Centre for Advanced Biomedical Imaging) took the audience of his Lunch Hour Lecture on 13 March on a journey to explore the greatest brain of the 20th century. The lecture to mark Brain Awareness Week drew in a large crowd; potentially explained by the promise of seeing a real brain!

Dr Mark Lythgoe (UCL Centre for Advanced Biomedical Imaging) took the audience of his Lunch Hour Lecture on 13 March on a journey to explore the greatest brain of the 20th century. The lecture to mark Brain Awareness Week drew in a large crowd; potentially explained by the promise of seeing a real brain!

The journey began with a video clip of Dr Lythgoe and Dr Jim Al-Khalili from the programme The Riddle of Einstein’s Brain (Channel 4, National Geographic USA, 2005). The two presenters were getting into a red convertible in southern California and setting off in search of the brain of Albert Einstein.

The presenters could not agree, however, on where genius originates from and consequently where it can be found. Is genius determined by biology and therefore can Einstein’s brain show us how? Or is genius a culturally dependent term that lives in the ideas produced?

Dr Lythgoe threw the question to the audience: “Did Einstein need to have published his work to be considered a genius? Or if he had done exactly the same amount of work and drawn the same conclusions, but never published, would he still be a genius?”

The results, although very close, suggested that the majority of the audience felt that Einstein would still be a genius even if his work had not been published.

Having prompted us to establish our initial opinions, Dr Lythgoe moved on to explore the journey of Einstein’s brain post-mortem.

Thomas Harvey

In 1955 when the pathologist Thomas Harvey found himself holding Einstein’s brain in Princeton hospital he had to make a decision. Again, Dr Lythgoe engaged the audience by asking the question, “What would you do?”

Harvey took the brain home, and kept its whereabouts – in fact its existence at all – secret. He sliced the brain into 240 pieces and in time passed on various sections to other academics.

Marian Diamond

Marian Diamond received some of the brain, and proceeded to study it. She discovered that when compared to normal brains, areas of Einstein’s brain had higher density of glial cells relative to neurons.

Work done since by Elizabeth Isaacs (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience) interestingly showed that children who struggled with maths had lower density of glial cells, suggesting a link between that area of the brain and proficiency in mathematics.

Sandra Witelson

Dr Witelson also managed to obtain some of the brain and in 1999 her study made headlines. She found macroscopic differences in Einstein’s brain, which had to date been overlooked.

The brain featured a larger-than-average parietal lobe, but more interestingly, it was structured as one compartment instead of the usual two, which are normally separated by the Sylvian fissure.

Dr Witelson’s study explained, “The findings do suggest that variation in specific cognitive functions may be associated with the structure of the brain regions mediating those functions.”

Elliot Krauss

In 1996 the remainder of the brain was passed to Dr Krauss, the chief pathologist at Princeton hospital.

Since this time a life-sized model of the brain has been constructed using photographs and stereolithography.

Wider perspective

Having given a history of Einstein’s brain through the second half of the 20th century, Dr Lythgoe moved on to explore possibilities about what the various findings could mean for the wider world.

He discussed, for example, Tommy, a patient who following a stroke suddenly began to write poetry, create sculptures and paint. This phenomenon indicated that changes to the brain could influence levels of creativity.

Another example was lab-based: Allan Snyder experiments within the field by stimulating neurones in the frontotemporal region before asking a participant to draw. This is designed to release the ‘inner savant’ and has produced anecdotal evidence for increased creativity.

It seemed that the lesson to be learnt was that brain structure influences function. However, Dr Lythgoe commendably reasoned that in Einstein’s case specifically, inferring a cause and effect is not that simple – was it the structure of his brain that made him brilliant? Or was it his excessive use of certain areas of his brain that resulted in structural changes?

By Jessica Lowrie, intern in UCL Communications & Marketing

One Response to “The Search for Genius: Einstein’s Brain”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] How could herpes possibly be a friend? Dr Mark Lythgoe explains. Filmed at the Times Cheltenham Scie…. […]