Did democracy cause the American Civil War?

By Ben Stevens H P Stevens, on 2 December 2011

The beauty of UCL’s Lunch Hour Lectures is that you don’t need any prior knowledge of the topic in question to enjoy one. This was certainly the case with Dr Adam Smith’s (UCL History) talk on 24 November, ‘Did democracy cause the American Civil War?’ – which is just as well, as my knowledge of that conflict is patchy at best.

Although I studied political history up to A level, American history rarely troubled the syllabus. However, I did learn, as every history student does, that wars very rarely have one, discrete cause.

Although I studied political history up to A level, American history rarely troubled the syllabus. However, I did learn, as every history student does, that wars very rarely have one, discrete cause.

In recognition of this, Dr Smith began by giving a succinct answer to the question in the lecture title: “No”. In fact, he said, the question was “phenomenally difficult to answer”, because although slavery is often cited as the main cause, it is actually the complex and unexpected interplay between democracy, slavery and modernity that lies at the heart of the conflict.

Abraham Lincoln wanted people to view the Civil War as first a test, and then an eventual triumph, of democracy, and it has come to be seen as a conflict between a progressive North and semi-feudal, backward South.

However, Dr Smith argued that it should not be framed in these terms. Modernity acted on both North and South in 1840s – through such democratising factors as print, the telegraph and the mobilisation of modern political parties – to create war.

The war was also “a great democratic failure”: government institutions were unable to contain the conflict and seven slave states seceded as a direct result of Lincoln’s election, due to his opposition to the expansion of slavery.

Rational and critical, the US was the world’s most advanced democracy in 1861, yet it was the only country where the dismantling of slavery led to four years of war and the loss of 650,000 lives.

Dr Smith’s thesis was that the very nature of American democracy increased the likelihood of war.

Slaveholders had rights not enjoyed in Europe or Brazil via a federal constitution that gave them advantages of representation. Democratic politics also gave them the capacity to build popular support, so that, although they were always a minority, they dominated Congress and were frequently elected President.

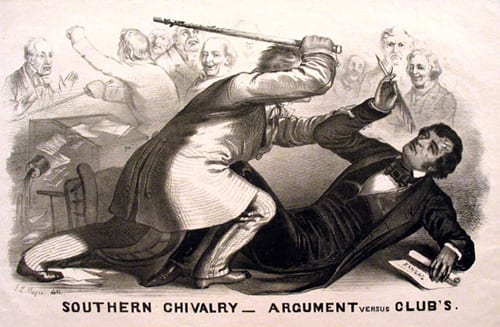

Such factors antagonised the abolitionist North, and democratic politics further led to the development of a Northern sectional consciousness – characterised by the song, ‘The North Is Discovered’, and images in the popular press demonising the South. For the first time, technology meant these could travel rapidly across the entire country.

A notorious example was a cartoon, Southern Chivalry: Argument versus Club’s (sic), by John Magee depicting Democrat Congressman for South Carolina Preston Brooks beating anti-slavery senator Charles Sumner almost to death on the Senate floor.

Thus, by the 1850s, there were two distinct national conversations and no ability to bridge this divide.

While the US had been built on compromise and non-partisanship, there was widespread frustration with compromise and ‘politics as usual’ in this period – and, according to Dr Smith, this was actually fed by democracy.

In particular, the 1850s saw the founding of the Republican Party – a self-styled ‘anti-party’ that was “fresh from the loins of the people”. The Tea Party anyone?

Overall, by 1860/61, there was huge pressure on politicians on both sides to accept war rather than to compromise – with correspondents imploring them to go to war.

At this point, Dr Smith addressed what is called ‘democratic peace theory’: the idea that democracies don’t go to war with each other.

Acknowledging that “it seems intuitively plausible that governments that listen to popular opinion are less bellicose”, he countered that war is not always a failure of democracy: it can also be an expression of democratic processes.

While never making clumsy, direct parallels with the present, Dr Smith’s lecture did paint an ominously familiar picture of an ever more polarised America, contemptuous of consensus and saddled with an intransigent, dysfunctional political system.

However, he struck a more optimistic note when asked in the Q&A session about lingering bitterness in the South.

Although he argued that the Civil War is “the defining event of US history” and that everything that has happened since – such as racial segregation and the Civil Rights movement – has been a response to it, he noted that the 150th anniversary has been marked by relatively little bitterness – especially in comparison with the centenary in the 1960s, which was highly politicised.

He also argued that the demographics of the South have changed hugely since then – though perhaps if recent research from the US Census Bureau is anything to go by, a painful post-Civil War economic legacy remains.

Ben Stevens is Content Producer (Editor) in UCL Communications & Marketing.

Watch video of the lecture here:

Close

Close