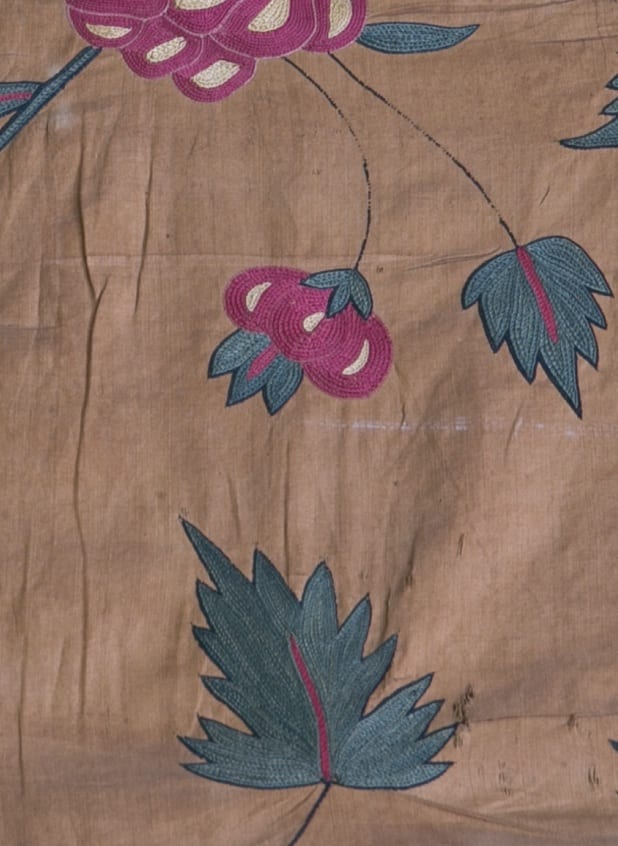

Figure 15: Indian embroideries at Osterley, ca. 1700-1725, Gujarat, India. Photo Courtesy: Stuart Howat.

During Francis Child the elder’s tenure as EIC committee member and later as a Director, the Company was responsible for augmenting the trade in cotton textiles from India, with calicos accounting for nearly three-quarters of Company trade. The enhanced supply of cotton fabrics and prints into Britain not only upset social hierarchies of elite and everyday use of printed fabrics, but also posed a threat to the livelihoods of wool and silk weavers.[1] In 1721, imported cotton textiles of every description from India, whether pure cotton or mixed composition, were banned and restrictions were placed on the sale of most cotton textiles through what were known as the Calico Acts (1690–1721). This prohibition was not lifted until the 1770s.[2] However, the prohibition was not so successful in curbing the demand for cotton prints and fabrics, the supply of which was picked up by the English East India Company.[3] Some of the best Indian embroideries to enter Osterley appear to date from this period of turmoil and prohibition.[4]

Indian Textiles

India gained a key position in the thriving Indian Ocean trading network through its ability to market a wide range of goods at competitive prices. The subcontinent’s central position on the sea route from East Africa to China made it a strategic stopover for commercial exchange and mercantile activity. The port city of Surat was called the “Blessed port” by India’s ruling Mughal dynasty.[5] Bombay, Madras and Calcutta were also flourishing mercantile hubs and the sites of some of the earliest “factories” set up by the Dutch, French and English East India Companies. Many Indian maritime merchants also owned ships and ran conglomerates both privately and in partnership with the East India Company. Indian textiles, especially the coarse cotton varieties produced in the Coromandel Coast and the Gulf of Cambay (modern day Gujarat) fed into the large-scale demand in the eastern markets of Indonesia, Malaya and China as well as the markets of the Red Sea, Persian Gulf and East Africa. Company merchants arrived in India to find an established textile culture of painted fabrics, block printing, and embroidery. Gradually, a more specialized market for high-value textiles such as Dhaka muslins and Gujarat silks and embroideries were created for private trade, and especially sought after by Company officials and merchants. English private traders were one of the most important groups of European traders in the eighteenth century and although there was no clear official ruling allowing this, Company servants regularly sanctioned their mercantile activities through carefully crafted indulgences of Company policy.

The Indian Embroideries at Osterley

At Osterley, the opulent silk embroidered bed pelmet cover and canopy in Mrs Child’s bedchamber was likely bought at Surat around 1700-1730, during the height of the popularity of Cambay embroideries in Europe. The textile features a plain cream background, which is contrasted with brightly embroidered patterns of thin branches and leaves in a dark green colour and red and yellow flowers. It is now understood that these embroideries were created by the artisans of the Mochi (cobbler) caste of Gujarat who originally worked the delicate chain-stitch hook and needlework on leather and later adapted this technique on to cloth.[6] The weavers, it is thought, operated in groups under headmen who were left in charge of actual negotiations and contracts, though there were some individual weavers as well.[7] The weaving process itself was quite seasonal with the best weaving done during the rains since the moist air was less brittle for the threads. Thus most agreements and orders were usually placed before the monsoons set in and the raw cloth dyed and cured in the autumn sun.[8] The Mughal court also actively patronized embroidered textiles, but after the rise of European trade in the subcontinent their designs were adapted to suit the demands of Company trade. By the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the monopoly of the English East India Company in Gujarat had significantly declined, though it retained the factory in the port town of Surat on the western coast of Gujarat.

China and Textiles

China was the primary exporter of silk to the East India Company in the eighteenth-century supplying both raw silk for English weavers as well as bulk silk textiles for retailers with the finer pieces reserved for private trade. Popular designs on silks included a combination of painted patterns and embroidered motifs of flowers, leaves, birds and animals. which were part of the craze for a decorative style broadly known as “china-worke” or chinoiserie in Europe. This “oriental” style could be copied in India or China from European pattern books brought through sea trade.

Figure 17: Detail of Chinese painted silk bed hanging at Osterley House. Photo Courtesy: Stuart Howat.

The Canton Factory records for the year 1732 give a particularly vivid account of the commission of painted silks by EIC supercargoes: ‘We gave each merchant [at Canton] a particular charge that their skills be made of the best Nankeen silk, that the flowered silks be all new patterns & collours as near as possible to the patterns we delivered them, that the taffaties & gorgorons have a good gloss on them.’[10] The official purchases by the East India Company in that year also included 308,435 pieces of chinaware for 17,4811/2 tael and 20, 560 pieces of woven silk for 141,852.4 tael along with specific orders for taffetas, handkerchiefs, poisees, satins and bed damasks. The inventory from July 1732-January 1733 also lists an order of: 11,907 taffetas, 2800 handkerchiefs, 2400 poisees, 100 goshees, 863 padasoys, 500 satins and 500 bed damasks.[11]

In the backdrop of political warring and unrest between the Company and the Mughal ruler Shah Alam II (r. 1759-1806) the EIC experienced a decline in silver reserves that consequently weakened their power to purchase raw silk. In a letter to Thomas Hodges Esq., Governor of the Council of Bombay Captain Payne reported that they ‘… are sorry to find that you Gentlemen are much in the same situation as those at Madras and Bengal but as Peace is restored we hope that Trade will flourish. Our being disappointed of silver from Bengal and Madras has obliged us to fill our sixteen ships with China ware and tea and not an ounce of Raw silk, which we find bears a good price in Europe.’[12] Thus, Company trade in India and China was closely connected and political fluctuations at either end impacted the nature of commodities that could be shipped back to Europe.

The textiles at Osterley encompass complex creative processes in design practice brought about through networks of East India Company trade in Asia. They highlight the central role of East India Company sea trade in creating a global economy of artistic exchange that shaped the domestic interior in England.

[1] For an overview of the cotton trade see Beverly Lemire, Fashion’s favourite – the Cotton Trade and the Consumer in Britain 1660-1800 (London: Oxford University Press, 1991). Also, Georgio Reillo, Cotton: The Fabric that made the Modern World (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

[2] Chapman, 35.

[3] Lemire (1991), p. 90.

[4] We are most grateful to Rosemary Crill at the Victoria & Albert Museum for her input on dating the Indian embroideries to between 1700-1725.

[5] Ashin Das Gupta, Indian merchants and the decline of Surat c. 1700-1750 (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 23. First Published by Franz Steiner Verlag, 1979.

[6] Rosemary Crill, Indian Embroidery, (V&A Publications, 1999), 12.

[7] Ashin Das Gupta, Indian merchants (2004), 34.

[8] Ashin Das Gupta, Indian merchants (2004), 60.

[9] John Irwin, “Origins of the ‘Oriental Style’ in English Decorative Art” Burlington Magazine

97, No. 625 (1955): 106-114. Also see, John Styles, ‘Indian Cottons and European Fashion, 1400-1800’ in Glen Adamson, G. Riello, and S. Teaseley, eds. Global Design History (Routledge, 2011), 37-46.

[10] 8 July 1732, Diaries of the Council of China, 1732, British Library G/12/33.

[11] Diaries of the Council of China, BL G/12/33, 1732.

[12] BL IOR/R/10/7, 1769/70, p. 66.