Josiah Child and the Wanstead Estate

By Hannah Armstrong

Please note that this case study was first published on blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah in April 2014.

The case study was last checked by the project team on 19 August 2014. For citation advice, visit ‘Using the website’.

In 1665, diarist Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) recorded his visit to politician Sir Robert Brooke’s residence at Wanstead describing it as ‘a fine seat, but an old fashioned house and being not full of people, looks desolately’.[i] Brooke (c.1637-69) had retired to France and the manor purchased from his father-in-law Sir Henry Mildmay (1594–1664/5), master of the King’s Jewel House and one of the judges at the trial of Charles I, had become somewhat neglected. It is of little surprise that Pepys described Wanstead as old fashioned as neither Mildmay nor Brooke appear to have carried out any architectural improvements. It is therefore likely that when Josiah Child (1635-1699) purchased the Wanstead estate in 1673, it appeared much as it did when Sir Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester (1532/3–1588) resided there from 1578 until his death in 1588.

Child had rented the property since 1667, but his acquisition in 1673 is an indication of the upwardly rising social and financial status of those who acquired their fortunes from a mercantile career. Upon his visit in 1683, diarist John Evelyn (1620-1706) described Wanstead as ‘a cursed barren spot, where commonly these over growne men seat themselves’.[ii] Such a scathing description seems ill justified if one considers the rich history of the site prior to Child’s acquisition. Wanstead frequently hosted royal visits, including those made by Henry VII, Mary I, Elizabeth I and Charles I. Furthermore, archaeological evidence suggests that a Roman villa once stood on the site, therefore demonstrating that Wanstead has been a place of significance from an early period.[iii] Its proximity to London, a major road and the river Roding in addition to its royal associations in fact made Wanstead far from the ‘cursed barren spot’ Evelyn describes. His reaction is likely to have been due to the growing discomfort amongst aristocratic circles of the ‘new men’ entering into the upper echelons of society and potentially corrupting elite manners, morals and social hierarchy.[iv]

The purchase of an already existing country seat is likely to have appealed to Child on account of its rich history in the absence of his own aristocratic lineage. However, when discussing Child’s acquisition of Wanstead in 1673, it is important to recognise that he was relatively unusual in the acquisition of an estate. Studies by Alan Mackley and Richard Wilson, Peter Earle and Margaret Hunt all comment that the acquisition of a country seat by newly moneyed men was less common than we are generally led to believe.[v] Hunt comments that the fear of being distant from business in the city and the drain on one’s capital in fact kept many business men from adopting an ‘aristocratic lifestyle.’[vi]

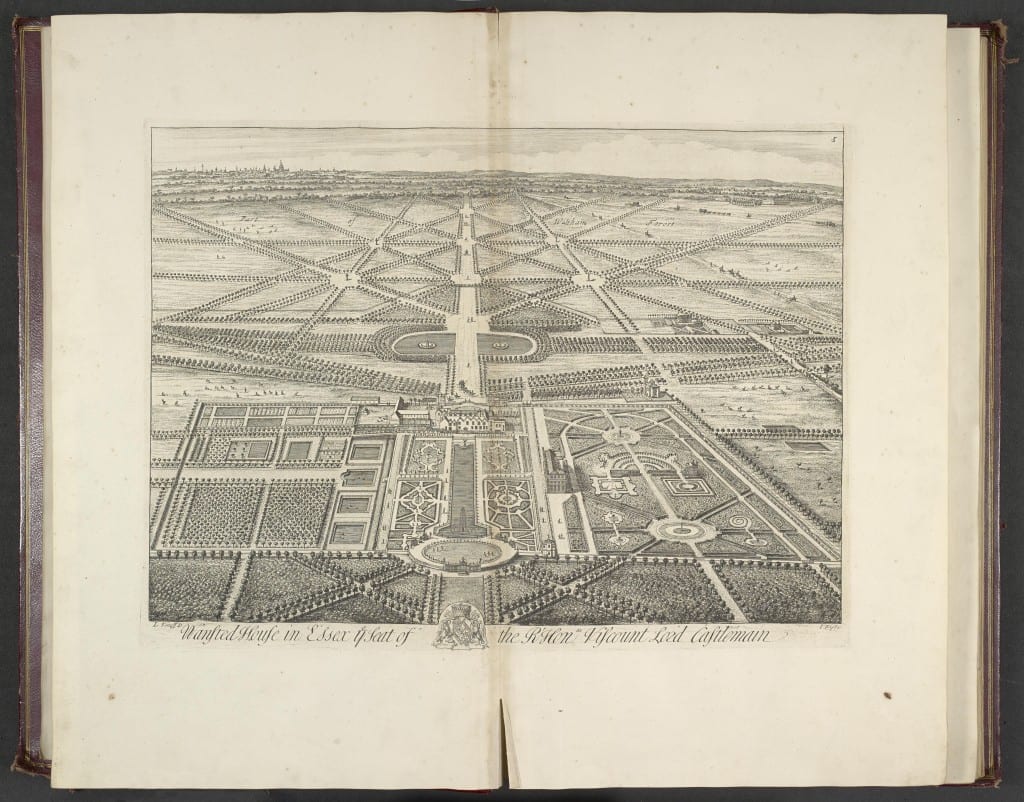

Those eager to maintain a strong presence in the city whilst also enjoying the luxuries entitled to gentlemen in a country retreat, tended to purchase smaller suburban properties in areas peripheral to London rather than a large country house such as Wanstead.[vii] Child’s purchase of a country seat indicates that he was keen to pursue an aristocratic lifestyle. At the same time Wanstead’s proximity to London enabled Child to maintain his business and political interests whilst doing so. Kip and Knyff’s series of engraved views of Wanstead demonstrates the significance of this proximity by including a view of the city and the spire of St Pauls Cathedral in the top left background (see below). Alongside Wanstead the popularity of areas such as Essex amongst the mercantile elite is demonstrated by other properties belonging to merchants nearby such as Sir Thomas Webster at Copped Hall and later the East India Company captain, Charles Raymond who lived at Valentines Mansion in Ilford during the eighteenth century. [viii]

Figure 1: Johann Kip and Leonard Knyff, ‘View of Wanstead House and Gardens for the Honourable Richard Child 1st Earl of Tylney, from the east’ included in Supplement du nouveau theatre de la Grande Bretagne (London: J. Groenewegen & N. Prevost, 1728). © British Library Board, 191.g.14.p.98.

Historian William Letwin describes Child’s purchase as indicative of his flourishing position, stating that ‘from this time on, Child began to enjoy the reputation of uncommon wealth’.[ix] Whilst Child is best known for his involvement in the East India Company, this was not in fact a source of wealth that financed the purchase of Wanstead. Child and his business associate Thomas Papillon had provisioned East India ships as early as 1659, however he did not become a shareholder in the Company until 1671. When Child purchased Wanstead in 1673, he owned only 2 per cent of company stocks. Therefore contrary to common consensus, Child’s acquisition was not financed by East India Company wealth, but by other means such as his role as a founding member of the Royal African Company in 1671, as treasurer to the Navy in Portsmouth, and through the ownership of a sugar plantation in Jamaica and a brewery in Southwark, London.[x]

Evelyn commented on Child’s upwardly rising position in 1683, describing Child as ‘from an ordinary Merchants Apprentice, & managements of the E. India Comp: Stock, being arrived to an Estate of (tis said) £200,000 pounds’.[xi] Such commentary by Evelyn suggests that Child’s success was recognised as a major achievement during this period. In 1675, Child’s shares in the East India Company equated to £12,000, and by 1679 this had increased to £23,000, making Child the largest stock holder in the Company. Further success came about in 1681 when Child was elected as Governor of the East India Company. In 1684 he served as Deputy Governor, until 1686 when he was once again Governor for another two years. He returned to his position as Deputy Governor again in 1688 until 1690.

Child’s influence and domineering power made him immensely successful but widely disliked. The London Society Magazine stated that ‘by his great annual presents Child could command both at Court and at Westminster Hall, what he pleased’.[xii] In order to secure a royal charter for the East India Company, Child reportedly bribed King Charles II on the 12 October 1681 with 10,000 guineas, an annual bribe until the revolution in 1688. James II also bowed to Child’s domineering nature and renewed the 1682 Royal Charter for the East India Company when given East India shares worth £10,000 in 1687.[xiii] The 1867 study Citizens of London from 1060-1867, estimated that in 1693, £100,000 were spent in bribery to obtain the new charter for the East India Company.[xiv]

Although the East India Company did not provide the necessary finances for the purchase of the estate, it did fund the ongoing maintenance and improvement of Wanstead. General historiography on the subject of country seats tends to consider architecture to be of utmost importance and the most effective means of disseminating power. Adrian Tinniswood’s study of country house visiting, for example, states that representatives of the new class of entrepreneurs in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were major builders, keen to consolidate their position and distance themselves from their humble roots.[xv] Child however, did not rebuild the Wanstead manor but instead carried out extensive landscape improvements.

The lack of primary sources makes it difficult to establish exactly why Child carried out landscape rather than architectural improvements. It is possible that rebuilding was too expensive and not something that Child was prepared to undertake after his initial acquisition. Despite this, the cost of landscape improvements was still considerable. In 1691, James Gibson recorded his visit to Wanstead, and listed vast numbers of elms and ashes as well as two large fish ponds by his out-gate of which he claims the fish stock to cost around £5,000 and the plantations ‘twice as much’.[xvi] There are two possible factors which may have contributed to Child’s decision towards landscape improvements, the first being to complement the grandeur of the already existing Elizabethan manor, and the second factor being to prepare the Wanstead estate for future descendants.

The acquisition of a country seat demonstrated an individual’s optimism in a lengthy future for his family at the estate. If Child believed in the longevity of country seat ownership then it is likely he expected rebuilding to take place at some point in the future. Indeed the rebuilding of Wanstead House took place shortly after Child’s death. Richard (1680-1750), Child’s youngest son and heir inherited the estate in 1704 and by 1715 had employed Scottish architect Colen Campbell to build a Palladian mansion on the site of the Elizabethan manor. Child’s landscape improvements may therefore have been in conjunction with ideas expressed in French gardener, Andre Mollet’s 1670 publication The Garden of Pleasure that ‘one ought to begin to plant even before the building of the House so that the Trees may become to half growth when the House shall be built’.[xvii]

Figure 2: Richard Westall. Wanstead House, Watercolor and graphite. Image courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Above all, the improvements carried out at Wanstead reflect Child’s upwardly rising position in the East India Company, which enhanced both his wealth and political power. The stronger he became, the greater the need for an estate that matched his significance. Little is known of the condition of the Wanstead gardens at the time of Child’s acquisition. Leicester’s household accounts list a number of payments made for the improvement of the garden such as, in April 1585 ‘to fower gardeneirs which made and sett a knot in the garden at Wansted,’[xviii] and three months later, to the gardener Thomas Gouffe for ‘graveling the garden at Wansted’.[xix] These designs however were likely to have been perceived as considerably outdated by 1673.

The only surviving pictorial evidence of Child’s landscape can be found in the three engraved views by Kip and Knyff. This series of engravings however were produced in 1712 and therefore date from after Child’s death when the estate belonged to his son Richard Child. This means that some of the features depicted by Kip and Knyff are works carried out by gardeners George London and Henry Wise in 1706. As a result, they are somewhat complex pictorial sources that conflate two different periods of ownership. It is therefore necessary to refer to contemporary descriptions of the gardens in order to establish which features were introduced by Child.

Figure 3: Avenue originally leading to the house, Wanstead Park. Photograph by Hannah Armstrong © 2013.

In 1683 Evelyn recorded his visit to Wanstead stating; ‘I went to see Sir Josiah Childs prodigious Cost in planting of Walnut trees, about his seate, & making fish-ponds, for many miles in Circuite, in Eping-forest’.[xx] Evelyn’s use of the active verbs ‘planting’ and ‘making’ indicate that these were recent or developing features at the time of his visit. In a poem by John Harris entitled Leighton-Stone-Air (1702) Wanstead is described as ‘a pleasant Villa in the Forest near Leighton Stone made very delicious by the New Plantations Sir Josiah Child has honoured it with’.[xxi] Harris also comments on ‘Chestnut-Avenues’ and `vaulted Grotts’. These are referenced in a footnote as `Grotts: Chestnuts and Abel-trees [Populus alba, white poplar] most delightfully planted round 2 vast Fish-ponds on the Forrest, projecting their beauty in the Water’.[xxii] The plantation of avenues was a potent expression of power in a landscape (see figure 3 above). The length of the avenues represented the extent of land belonging to its owner. In the centre of the axis of avenues stood the country seat, the central power of the estate and surrounding environment. Fish ponds were also popular for their ability to demonstrate an owner’s active involvement in the husbandry of his estate, whilst also serving as an ornamental feature.[xxiii]

Given Child’s links with the East India Company, it is tempting to suppose that he had access to the more exotic botanical species that were being introduced into England. The Kip and Knyff engraving Wanstead looking north, in two sections, depicts potted plants situated behind a brick wall nearby the house. This was a recommended technique to protect more exotic plant life such as orange and lemon trees from the wind.[xxiv] A green house designed by William Talman was constructed at Wanstead around 1706 to accommodate the more exotic plant life in need of warmer conditions. However both Kip and Knyff’s engravings and Talman’s greenhouse were produced after Child’s death and therefore we can only speculate whether such a collection of exotic plant life was directly linked to Child’s East India connections.

Following Child’s death in 1699, connections to the East India Company became increasingly tenuous. Aside from shared bonds, there seems to be little involvement in the company. Contemporary accounts describe the interiors at Wanstead to have included chintz and Indian papers but this could merely have been due to contemporary fashions rather than any direct link to the Company.[xxv]

Sadly, Child’s hopes for his family’s long, prosperous future at Wanstead were short-lived. In the early nineteenth century, Wanstead estate was under the ownership of William and Catherine Tylney Long Wellsley Pole. Catherine had inherited the estate in 1807 and with an annual income of £80,000 was a highly sought after heiress. Her decision to marry William Wellsley Pole, nephew of the Duke of Wellington was arguably a poor decision, for William was already struggling with debts at the time of their marriage in 1812. Within ten years, William and Catherine were faced with no alternative but to sell the contents of Wanstead House in order to pay off these extortionate debts. The final collapse came when the house was pulled to the ground and sold off as building material in 1824. All that now marks the site of the ‘princely mansion’[xxvi] is a large hole at the first tee on the Wanstead golf course (see figure 4 below).

A study of Wanstead differs from other case studies covered in the East India Company at Home project largely due to a lack of material evidence which makes it difficult to evaluate the extent to which connections with East India Company were reflected at Wanstead. The Wanstead case study also dates earlier than many of the houses discussed in the East India Company at Home project and therefore provides an early example of the ways in which the country seat was used as a tool to both enhance and reflect power and prosperity. The landscape improvements carried out by Child provide an insight into the types of landscape features that were fashionable in the late seventeenth century. Surviving contemporary descriptions of Wanstead largely comment on the landscape rather than the Elizabethan mansion, demonstrating that the gardens were a new feature worthy of commentary. As a result, this case study challenges existing historiography by demonstrating that landscape was equally effective as the country house for newly moneyed gentlemen to express new found status and wealth.

Above all, Josiah Child’s transformation of the ‘desolate’ seat, described by Pepys into one Evelyn estimated to be ‘worth £200,000’, demonstrates the effects a powerful role in the East India Company had upon lifestyle and social position in the late seventeenth century. Whilst the finances which supported the original purchase of the house came from other sources of income, the wealth accumulated by Child’s position in the East India Company enabled Child to create an impressive landscape that would soon accommodate one of the most influential Palladian mansions in the country and become recognised as one of ‘noblest houses in England’.[xxvii]

To read the case study as a PDF, click here.

Acknowledgements

The text and research for this case study was primarily authored by Hannah Armstrong who is a PhD student in History of Art at Birkbeck, University of London.

[i] Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys: A Selection, (ed.) R.Latham, (London: Penguin, 2003), p. 490.

[ii] John Evelyn, The Diary of John Evelyn, (ed.) E.S de Beer, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), pp. 305-306.

[iii] Compass Archaeology carried out a survey on Wanstead for English Heritage in February 2013 and reported evidence of Roman activity on site between 43-104AD.

[iv] Lawrence & Jeanne Stone, An Open Elite? England 1540-1880 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), p. 29.

[v] See Margaret R, Hunt, The Middling Sort: Commerce, Gender and the Family in England 1680-1780, (University of California Press, London, 1996); Alan Mackley & Richard Wilson, Creating Paradise: The Building of the English Country House 1660-1880, (London: Hambledon & London, 2000); Peter Earle, The Making of the English Middle Class, (London: Methuen, 1989).

[vi] Hunt, The Middling Sort, p. 3.

[vii]Osterley House serves as another example of a major country seat within close proximity to London. Like Wanstead, Osterley was a site of significance during the Elizabethan period. It was acquired by the financial advisor to Queen Elizabeth 1st, Thomas Gresham (1519-1579) in 1562 and was therefore frequently visited by the Queen. In 1713 it was acquired by the son of a cloth merchant, Sir Francis Child the Elder. Similarly to Wanstead, it was Francis’ son Robert Child, director of the East India Company that in fact developed Osterley into an impressive estate. Like Wanstead, Osterley House demonstrates the importance of proximity between country seat and the city of London where frequent visits into the city were necessary in order to enforce the Osterley’s family role and control in the East India Company. See the case study of Osterley House for East India Company at Home by Yuthika Sharma and Pauline Davies.

[viii] A New Map of the County of Essex by Henry Overton, (1713), British Library Maps Collection, K.Top.13.2, depicts country seats within the county. Nearest to Wanstead are ‘Cope Hall’ and ‘Havering’. In 1564 Copped Hall was granted to Sir Thomas Heneage by Queen Elizabeth 1st. Heneage rebuilt the mansion and it was complete in time for a royal visit in 1568. This is another example of the Queen’s frequent visits to country seats in Essex. In 1694, the house belonged to the 8th Earl of Dorset and was purchased in 1701 by Sir Thomas Webster, son of a wealthy merchant. Valentines Mansion was bought by the city merchant and banker Robert Surman in 1720. Although this acquisition dates after that of Child, it further demonstrates the popularity of seats in Essex amongst the mercantile elite.

[ix] William Letwin, Sir Josiah Child, Merchant Economist (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1959), p. 16.

[x] Richard Grassby, ‘Child, Sir Josiah, first baronet’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online, www.oxforddnb.com, Accessed: 08/03/2013

[xi] Evelyn, The Diary of John Evelyn, p. 305.

[xii] The Merchant Princes of England, London Society, an illustrated Magazine of light and amusing literature for the hours of relaxation (March 1865), Vol 39, p. 264.

[xiii] Richard Grassby, ‘Child, Sir Josiah, first baronet’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online, www.oxforddnb.com, Accessed: 08/03/2013

[xiv] Benjamin Brogden-Orridge, Some Account of the Citizens of London and their Rulers, from 1060-1867 (London:William Tegg,1867), p.174.

[xv] Adrian Tinniswood, The Polite Tourist (London: National Trust, 1998), p.16.

[xvi] Compass Archaeology Survey (May 2013), p. 46.

[xvii]Andre Mollet, The Garden of Pleasure (London 1670), p. 2.

[xviii] Simon Adams (ed.), Household Accounts and Disbursement books of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester 1558-1561, 1584-1586 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 178.

[xix] Ibid, p. 279.

[xx] Evelyn, Diary of John Evelyn, p. 305.

[xxi] Joseph Harris, Leighton Stone-Air, a poem. Or a poetical encomium on the excellency of its soil, healthy air and beauteous situation (London 1702), p.33.

[xxii] Ibid, p. 34.

[xxiii] Tom Williamson, Polite Landscapes (Baltimore: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1995), 33-34; Christopher K. Currie, ‘Fishponds as Garden Features, c.1550-1750’, Garden History, 18:1 (Spring 2008), 22-46.

[xxiv] John Worlidge, Systema horti-culturae, or, The art of gardening in three books, (1677), p.16; T. Langford, Plain and full instructions to raise all sorts of fruit-trees that prosper in England in that method and order, that everything must be done in (London, 1681), pp. 51-61; David Jacques, ‘Garden Design in the Mid Seventeenth Century’, Architectural History, 44 (2001), pp. 365-376; Thanks also to Sally Jeffery for a discussion on the gardens at Wanstead, see Sally Jeffery, ‘Wanstead House and Gardens in the Eighteenth Century’, The later Eighteenth Century great house (Oxford, 1997), pp. 76-99.

[xxv] Peter Kalm, Account of his visit to England on his way to America (1748), p.176

[xxvi] Wanstead House, Essex. Magnificent Furniture, Collection of Fine Paintings and Sculpture, Massive Silver and Gilt Plate, Splendid Library of Choice Books, The Valuable Cellars of Fine-Flavoured Old Wines, Ales, &c., &c. (London: J.Brettell, 1822).

[xxvii] Peter Muilman, A New and Complete History of Essex, 6 vols (Chalmsford: M. Hassall, 1769-72), IV, p.229.