How does testing HPV positive make women feel about sex and relationships?

By rmjlkfb, on 21 August 2019

A previous blog described how a new way of looking at cervical screening samples called primary HPV testing is being introduced into the NHS Cervical Screening Programme. In this post, we will describe the results from our recently published review which looked at whether testing HPV positive has an impact on how women feel about sex and relationships.

Why might testing HPV positive have an impact on sex and relationships?

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a very common sexually transmitted infection (STI). It’s so common that most men and women will be infected with HPV at some point in their life, often without them knowing. Because of the sexually transmitted nature of HPV and with the introduction of HPV primary testing in England, we wanted to find out whether testing HPV positive could have an impact on sex and relationships. We reviewed all previous research that has explored the impact of an HPV positive result on sex and relationships among women.

What did we find?

There were 12 quantitative studies, which used surveys to collect data on a range of different outcomes such as sexual satisfaction, frequency of sex, interest in sex and feelings about partners and relationships. The results from these studies were very mixed with some studies suggesting that testing HPV positive did have an impact on sex and relationships and others suggesting that it didn’t.

Three main themes emerged from the 13 qualitative studies, which mainly used interviews to collect data:

- Source of HPV infection – women were concerned about where the infection came from and whether it came from a current or previous partner. Some expressed concerns that their partner had been unfaithful and wondered whether that was how they had acquired HPV.

- Transmission of HPV – concerns about passing on HPV to a partner were common. Some women were also worried about infecting their partner and their partner re-infecting them, not allowing the virus to be cleared and increasing the risk of cervical cancer.

- Impact of HPV on sex and relationships – Some women reported a reduced interest in and frequency of sex following HPV. HPV had a negative impact on some women’s sexual self-image. The risks associated with oral sex were mentioned by a few women who were concerned about passing HPV on to their partners in this way.

What do our findings mean?

It is possible that testing HPV positive may have an impact on sex and relationships for some women, however the extent of this is unclear. As none of the studies included in the review were in the context of primary HPV testing, this work highlights the need for further research in this context. As primary HPV testing is introduced more widely, it is important to understand the impact of an HPV positive result on sex and relationships to ensure that this does not cause unnecessary concern for women.

I don’t need cervical screening anymore – or do I?

By Laura Marlow, on 9 August 2019

By Laura Marlow, Mairead Ryan and Jo Waller.

Having cervical screening (smear tests) when you are older is just as important as when you’re younger, yet many women aged 50-64 years do not attend when invited. One reason older women decide not to attend anymore is because screening can become more uncomfortable after the menopause. We previously explored the potential for doing screening without a speculum as an alternative for these women. Another reason that some older women give for not attending their screens, is that they no longer feel it is relevant for them because they are no longer sexually active or have had the same partner for a long time.

Cervical cancer is caused by HPV, an infection which is passed on through sexual contact. But it can take a long time for HPV to develop into cervical cancer, so past rather than current sexual behaviour is what’s important. For an older woman, HPV can be the result of an infection acquired many years ago. In our latest study, published this week in Sexually Transmitted Infections, we wanted to see if explaining this long timeline between acquiring HPV and developing cervical cancer could help to increase the extent to which older women saw screening as relevant to them.

We recruited women aged 50-64 years who said they would not go for screening again and asked them to read some information about HPV. We then looked at changes in their perceptions of cervical cancer risk and intention to go for screening. All women read basic information about HPV but some of the women also read the statement:

“Women aged 50-64 should be aware that HPV can take a long time to develop into cancer (10-30 years). This means that even if you have not been sexually active for a long time or have only had one partner for a long time, you could still be at risk of cervical cancer”

Women who read this additional information were more likely to increase their perceived risk of cervical cancer and to increase their intentions to attend when next invited. In the group who read this information a quarter of women increased their intentions to be screened compared with just 9% of the control group (who only read basic information about HPV). While this study is experimental, and measured intention to go for screening (not actual behaviour), it suggests that explaining the long time interval between getting HPV and developing cervical cancer may be a useful way to increase cervical screening intentions in those who do not plan to attend.

Making it easier to book for cervical screening

By Laura Marlow, on 12 July 2019

Authors: Mairead Ryan, Jo Waller, Laura Marlow

Over a quarter of all women who are eligible for cervical screening in Great Britain are currently overdue (that’s more than a million women). In a previous blog, we described our work showing that around half of these women want to be screened, but have not got around to going. When we talked to women about practical barriers to screening; they mentioned how the current booking process can be difficult and inflexible. In this piece of research, we wanted to explore how women feel about other booking options that might help them make the leap from intending to go for screening to actually booking their appointment.

Published in BMJ Open this week, our survey of 614 women found that half find it difficult to get through to a receptionist, 31% find it difficult calling during GP opening hours and 31% forget to book an appointment altogether. Women who were currently overdue for screening reported more practical barriers than those who were up-to-date. They were also more likely to say they might forget to book an appointment.

Women were asked how acceptable they would find different ways of receiving their screening invitation. Posted letters, which is how women are currently invited, were the most acceptable option (93%), but most women said they would be happy to receive their invitation by text-message (81%), mobile phone-call (76%) or email (75%).

We also asked women about alternative ways of booking their appointment. We found that many would consider booking online, either through a website on a computer (60%) or using their smartphone (59%). Younger women were far more likely to be happy with online booking and women who reported more barriers to booking an appointment showed greater interest in using online booking methods.

We asked women who did not like the idea of email or text invitations why this was and the most common concerns centred around privacy or ‘missed’ invitations. Using multiple modes to invite women to screening, i.e. utilising text messages alongside traditional paper invitations, could be a good option. In fact, text message reminders are already being rolled out across London.

We asked women who did not like the idea of email or text invitations why this was and the most common concerns centred around privacy or ‘missed’ invitations. Using multiple modes to invite women to screening, i.e. utilising text messages alongside traditional paper invitations, could be a good option. In fact, text message reminders are already being rolled out across London.

Online booking options could overcome the most common practical barriers highlighted by participants, including ‘difficulty getting through to a receptionist’ and ‘difficulty calling the practice during opening hours’. While online booking is an option in some GP practices already, the current screening invitation letter doesn’t mention this. Signposting online booking services to women when they are invited for screening may be an effective way of improving the appointment booking process. But ensuring that traditional telephone booking options remain available is important for older women who may not be so comfortable with online booking.

A new test for cervical screening is being rolled out, but how do the screening test results make women feel?

By Jo Waller, on 3 July 2019

By Emily McBride and Jo Waller

You might have heard that cervical screening is changing in England. If not, we’ve got you covered. In this post, we’re going to talk about the new cervical screening approach (called HPV primary screening), as well as our recently published research examining the way the test results make women feel.

What will happen under the new approach to cervical screening?

Soon all women who get screened in England will be tested for human papillomavirus (HPV), using an approach called HPV primary screening. HPV is a really common sexually transmitted infection which the body usually clears it on its own without it causing any problems. In fact, 4 out of 5 women have HPV at some point in their life. Sometimes, however, when the body can’t clear HPV, the virus can cause abnormal cells in the cervix to develop. With HPV primary screening, women who test positive for HPV will also have the cells in their cervix checked for any abnormal changes. However, women who test negative for HPV don’t get checked for abnormal cells because their risk of cervical cancer is really low – they don’t need to come back to screening again for another 3-5 years. Researchers have estimated that this new and improved screening approach will prevent an extra 500 cervical cancers a year in England. Screening can prevent cancer by picking up and treating cell changes before they develop into cancer.

How did women in our study feel after receiving their cervical screening test results?

Over the last few years, we’ve been doing a survey with women in areas where HPV primary screening has been tried out. We wanted to know how women felt about receiving the different test results at HPV primary screening compared with standard screening results. One test result was of particular interest to us because it’s new using this approach – HPV positive with normal cells (no abnormal changes). Women getting this result were asked to come back to screening 12 months later to see whether their body had cleared the HPV and to check no abnormal cells had developed. We thought it was possible that these women might feel anxious about being told they had HPV but having to wait 12 months to be screened again.

So what did we find? Well, women in the new group (HPV positive with normal cells) tended to be more anxious than those with normal results, and to be more worried about the result and about cervical cancer. But reassuringly, those who had come back for a second HPV test 12 months after their first positive result had similar anxiety levels to those getting a normal result. This suggests that being told you have HPV for the first time leads to feelings of anxiety and worry, but these are probably temporary for most women.

What do our research findings mean for cervical screening?

findings mean for cervical screening?

As the switch to HPV testing is introduced across the country, it’s really important for women taking part in screening to understand what the test is for and what the results will mean. Many women who go for screening don’t always read the information that’s sent with their invitation. This means practice nurses and other health professionals delivering screening have a key role to play in talking to women, making sure they understand what the change to the programme means, and encouraging them to read the new cervical screening leaflet. It’s also really important that health professionals and the cervical screening programme help support women who are anxious and are able to address the common concerns. We’re continuing to work closely with the NHS and Public Health England to help word HPV primary screening result letters. We also recently co-created a ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ information section to go alongside the HPV positive result letters, which we hope will help to mitigate unnecessary anxiety.

What do women who are overdue for cervical screening know about the risk factors for cancer?

By Jo Waller, on 21 May 2019

Authors: Mairead Ryan, Laura Marlow and Jo Waller

Attending cervical screening between 25-64 years (every 3 or 5 years depending on age) means abnormal cells on the cervix can be picked up and treated before they develop into cancer. In the UK, about 3,100 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer each year and 850 die of the disease. This number could be reduced if more women were up-to-date with screening, but the proportion of women who are overdue for screening is increasing every year, across all age groups.

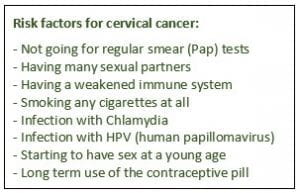

To make an informed choice about participation in screening, it’s important that women understand the things that increase their chances of developing cervical cancer. In particular, they need to know that their risk is higher if they don’t go for screening. In our study, just published in Preventive Medicine , we surveyed women aged 25-64 (793 participants) who were either i) overdue for screening or ii) did not intend to go for screening when next invited. The aim of the study was to assess whether women who decline screening are making this decision based on a good understanding of cervical cancer risk factors. We asked women to say whether they thought that certain risk factors could increase a woman’s chance of developing cervical cancer. All eight risk factors that we showed are known to increase cervical cancer risk, so women with good knowledge should have selected them all.

We found that many women had low awareness. Only just over half (57%) of the participants recognised that ‘not going for regular smear (Pap) tests’ may increase a woman’s chance of developing cervical cancer and far fewer recognised ‘infection with HPV’ as a risk factor (29%). We also found that women from non-white ethnic backgrounds were less aware that not going for regular screening could increase their risk of cervical cancer, compared with white British/Irish women.

These findings suggest that many women are not making informed choices about screening. All women included in our survey should have been sent educational leaflets about cervical screening, but as our previous research in bowel screening shows, women may not be reading these or remembering their content. Further public health action is needed to explore effective communication methods, including non-leaflet approaches, to ensure that all women are making an informed decision about cervical screening (non-)participation.

Lessons from a (not so) rapid review

By Robert Kerrison, on 7 March 2019

Authors: Robert Kerrison, Christian von Wagner, Lesley McGregor

Introduction

Systematic reviews enable researchers to collect information from various studies, in order to create a consensus. One of the major limitations of systematic reviews, however, is that they generally take a long time to perform (~1-2 years; Higgins and Sally, 2011). Often, it is the case that an answer to a question is required quickly, or the resources for a full systematic review are not available. In such instances, researchers can perform what is known as a ‘rapid review’, which is a specific kind of review in which steps used in the systematic review process are simplified or omitted.

As of right now, there are no formal guidelines describing how to perform a rapid review. A number of methods have been suggested (Tricco et al., 2015), but none are recognised as being ‘best in practice’. In this blog, we describe our experience of conducting a rapid review, the obstacles encountered, and what we would do differently next time.

For context, our review was performed as part of a wider project funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research. The aim of the project was to develop and test interventions to promote flexible sigmoidoscopy (‘bowel scope’) screening use in Hull and East Riding. The review was intended to inform the development of the interventions by identifying possible reasons for low uptake.

Obstacles

Our first task was to select an approach from the plethora of options described in the extent literature. On the basis that many rapid reviews are criticised for not providing a rationale for terminating their search at a specific point (Featherstone et al., 2015), we opted to use a staged approach (previously described by Duffy and colleagues), which suggests researchers continue to expand their search until fewer than 1% of articles are eligible upon title and abstract review (the major assumption being that, if successive expansions yield diminishing numbers of potentially eligible publications, and the most recent expansion yields a relatively small addition to the pool, stopping the expansion at this point is unlikely to lead to a major loss of information).

After deciding an approach, our next task was to ‘iron out’ any kinks with the method selected. Several aspects of the review method were not fully detailed by Duffy and colleagues in their paper, and therefore needed to be addressed. Such aspects included: 1) how authors selected search terms for the initial search, 2) how authors selected the combination and order in which search terms were added to successive searches, 3) whether authors restricted search terms to titles and abstracts, 4) how many authors screened titles and abstracts and, 5) if two or more authors reviewed titles and abstracts, how disagreements between reviewers were resolved.

Through discussion, we agreed that: 1) the initial search should include key terms from the research question, 2) successive searches should include one additional term analogous to each of those included in the initial search (to ensure a large number of new papers was obtained), 3) the order and combination in which search terms should be added to successive searches should be based on the combination and order giving the greatest number of papers (i.e. to ensure that the search was not terminated prematurely), 4) search terms should be restricted to titles and abstracts, 5) titles and abstracts should be reviewed by at least two reviewers and, 6) disagreements between reviewers should be resolved through discussion between reviewers (see: Kerrison et al., 2019, for full details regarding the method used).

Experience

Having agreed an approach, and ironed out any issues with it, we were then faced with the task of performing the review itself. While this took less time to perform than a traditional systematic review, it was still a lengthy process (approx. 4 months). As per the systematic method, we were required to screen hundreds of titles and abstracts and extract data from many full-text articles. Perhaps the most time-consuming aspect of the entire review, was the process of manually entering the many different combinations of search terms to see which gave the largest number of papers for review at each stage. It is possible that, in the future, a computer programme could be developed to automate this process; however, this would only likely occur if the method was widely accepted by the research community.

After performing the review, we submitted the results for publication in peer-reviewed journals. Having never previously performed a rapid review, we were uncertain how it would be received. Disappointingly, our initial submission was rejected, but did receive some helpful comments from reviewers. While we were slightly discouraged, we decided to resubmit our article to Preventive Medicine, where it received positive reviews and, after major revisions, was accepted for publication.

Next time

So, what would we do differently next time? For a start, we’d consider using broader search terms. Our searches only detected 52% of papers prior to searching the reference lists of selected papers. We think that the main reason for this is that search terms were restricted to abstracts and titles, which often did not mention ‘flexible sigmoidoscopy’ (or variants thereof), specifically. Instead, most papers simply referred to the predictors of all colorectal cancer screening in the abstract (key words we had not included in our search terms in order to reduce the number of irrelevant papers reviewed), and then the predictors of each test in the main text. This problem is likely to repeat itself in other contexts (e.g. diagnostics and surveillance).

Another key change we would make would be to include qualitative studies and appropriate search terms to highlight these. Employing a mixed methods approach would help explain some of the associations observed, and thereby how best to develop interventions to address inequalities in uptake.

Final thoughts

Conducting a ‘rapid’ (4 months!) review has been an enjoyable experience. Like any research, it has, at times, been difficult. A lack of formal guidance, available for many forms of research today, made the process perhaps harder than it needed to be. With rapid reviews becoming increasingly common (read all about this here), it is our hope that this blog and paper will help make the process easier for others considering rapid reviews in the future.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research (registered charity 516898; grant number: UCL407)

References

Duffy, S. W., et al. (2017). “Rapid review of evaluation of interventions to improve participation in cancer screening services.” Journal of medical screening 24(3): 127-145.

Featherstone RM, Dryden DM, Foisy M, et al. Advancing knowledge of rapid reviews: An analysis of results, conclusions and recommendations from published review articles examining rapid reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2015; 4(1): 50.

Higgins JP, Sally. G. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0. . 2011.

Kerrison, R. S., von Wagner C, Green T, Winfield M, Macleod U, Hughes M, Rees C, Duffy S, McGregor L (2019) Rapid review of factors associated with flexible sigmoidoscopy screening use. Preventive Medicine.

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, Perrier L, Hutton B, Moher D, Straus SE (2015) A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC medicine 13(1): 224

Fifty shades of cancer fear revisited

By Charlotte Vrinten, on 9 October 2018

Do you sometimes worry about how your life would change if you were diagnosed with cancer? Most people do. And perhaps unsurprisingly so, because research shows that if you are born after 1960, there’s a 50% chance that you’ll get cancer at some point during your life.*[1]

In a previous post, we described what it is that ordinary, healthy people worry about if they worry about being diagnosed with cancer, such as cancer treatment, how a diagnosis would affect loved ones, and death. But from the way we carried out that research, we couldn’t tell how common those worries are in the general population. We also couldn’t tell how these worries might influence engagement with cancer prevention and early diagnosis efforts, such as cancer screening. So in our latest two studies, we have looked at these questions.

In our first study, we examined how common twelve worries about cancer are.[2] We found that worries about the emotional and physical effects of a cancer diagnosis were much more common than worries about the social consequences. For example, two out of three people would be ‘quite’ or ‘extremely’ worried about the threat to life and emotional upset that a diagnosis would cause. One in two people would worry about surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and loss of control over life, while just under half would worry about financial problems or the effect of a cancer diagnosis on their social roles. One in every four people would be worried about effects on their identity, important relationships, gender role, and sexuality.

We also looked at whether some groups of people in the population worry more about these things than others. We found that women and those who are younger tend to worry more about all aspects of cancer. Interestingly, those from an ethnic minority background worried just as much about the physical and emotional impact of a cancer diagnosis as their White counterparts, but were more worried about the social consequences of a cancer diagnosis than those from White backgrounds. This might be because cancer tends to be more stigmatised or taboo in some ethnic minority communities,[3] and this is something we are currently doing more research on.

In our second study, we examined the association of these worries with uptake of screening for breast, cervical, and bowel cancer.[4] We found that men and women who worried about the emotional and physical consequences of a cancer diagnosis were more likely to take part in bowel cancer screening, while women who worried about the social implications of a cancer diagnosis were less likely to go for breast or cervical screening.

What can we conclude from this? First, being worried about cancer is an unpleasant emotion and may keep people from taking part in cancer screening or going to the doctor when they have a symptom that might be cancer. This could lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment, and worse outcomes. By better understanding what it is that people tend to worry about when it comes to cancer, we may be able to allay some of their worries, improve informed participation in screening, and encourage prompt help-seeking for symptoms.

* For those of you born before 1960, your chance of developing cancer during your lifetime is 1 in 3.

[1] Ahmad AS, Ormiston-Smith N, Sasieni PD. Trends in the lifetime risk of developing cancer in Great Britain: comparison of risk for those born from 1930 to 1960. British Journal of Cancer, 2015;112:943-7.

[2] Murphy PJ, Marlow LAV, Waller J, Vrinten C. What is it about a cancer diagnosis that would worry people? A population-based survey of adults in England. BMC Cancer, 2018;18:86.

[3] Marlow LA, Waller J, Wardle J. Barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women: a qualitative study. J Fam Plan Reprod Health Care. 2015;41:248–54.

[4] Quaife SL, Waller J, von Wagner C, Vrinten C. Cancer worries and uptake of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening: a population-based survey in England. Journal of Medical Screening, 2018. [Epub ahead of print]

A ‘fuzzy’ distinction between different groups of cervical screening non-participant

By Laura Marlow, on 17 August 2018

Over the last two years we have blogged about our work exploring different groups of non-participants at cervical screening (aka the smear test). We have shown that women who do not attend for their smear test can be either unaware of screening, unengaged with screening, undecided about screening, intending to get screened (but not yet got around to it) or they may have decided not to get screened.

In our most recent study funded by Cancer Research UK and published in Psycho-oncology, we interviewed women aged 26-65 years (n=29) from these different ‘non-participant’ groups to gain a deeper understanding of their screening decisions. We found that there are differences in the salience of particular barriers to screening, for example women who intend to get screened often focus on more practical barriers to screening and women who have decided not to attend often focus on past negative experiences of screening. However, there were also examples where even within groups of non-participants women had quite varied views e.g. some decliners felt the smear test procedure was not something they wanted to do, even though they knew the risks, other decliners thought smear tests were no big-deal but didn’t think they needed one because they weren’t at risk of cervical cancer.

Our findings also suggested that the distinction between different non-participant groups is ‘fuzzier’ than we originally thought. For example, many of the undecided women described not really wanting to have a smear test, but feeling less strongly about this than decliners. For women who intended to get screened, there were some that did not really want to attend, but felt they ought to (more similar to decliners or undecided women), while other intenders were happy to have a smear but practical barriers stopped them from participating.

This ‘fuzziness’ could mean that distinct interventions for one type of non-participant group may not work for some people in that group, but might work for others classified in a different way. Alternatively, there may be one intervention that could be successful across groups for different reasons, for example HPV self-sampling could address practical barriers (relevant to intenders) and concerns about the screening procedure (relevant to some decliners).

Can we help the public understand the concept of ‘overdiagnosis’ better by using a different term?

By rmjdapg, on 28 June 2018

Authors: Alex Ghanouni, Cristina Renzi & Jo Waller

We have previously written about ‘overdiagnosis’ – the diagnosis of an illness that would never have caused symptoms or death had it remained undetected – and how the majority of the public are unfamiliar with the concept and find it difficult to understand. We have also looked at the various ways that health websites describe it in the context of breast cancer screening; we previously found that most UK websites include some relevant information, in contrast to the last similar study from 10 years ago. This led us to think about how it might be possible to better explain the concept to people. Although ‘overdiagnosis’ is the most commonly used label, its meaning is probably difficult to infer if people are unfamiliar with it (and most people are). We wanted to test whether other terms might be seen as more intuitive labels that would help communicate the concept to the public.

We carried out a large survey in which we asked around 2,000 adult members of the public to read one of two summaries describing overdiagnosis. These summaries were based on information leaflets that the NHS has already used extensively in England. We asked people whether any of a series of possible alternative terms made sense to them as a label for the concept described and whether they had encountered any of the terms before.

What did we find?

A fairly large proportion of people (around 4 out of 10) did not think any of the seven terms we suggested were applicable labels for the concept as we described it. We also found that no single term stood out as being seen as particularly appropriate. The term most commonly endorsed (“unnecessary treatment”) was only rated as appropriate by around 4 out of 10 people. Another important finding was that around 6 out of 10 people had never encountered any of the terms we suggested and that the most commonly encountered term (“false positive test results”) was only familiar to around 3 out of 10 people. You can read the full paper here.

What were our conclusions?

We were disappointed that we did not find a term that was clearly considered to be an intuitive label for the concept of overdiagnosis. However, this was not entirely surprising because we know from several studies that it is unfamiliar to most people. It is not a given that this will always be the case: Organisations like the NHS and health charities are continually telling the public about overdiagnosis in various ways and if the concept becomes more familiar and better understood, people may be more inclined to identify a term that makes sense and which can then be used to communicate the concept. It is also possible that terms other than the 7 we looked at might already be suitable. Since the terms we looked at were generally unfamiliar, one recommendation we can make in the meantime is that it might be better to avoid specific labels like “overdiagnosis” when communicating the issue to people; explicit descriptions might be more helpful.

Smokers’ interest in a national lung cancer screening programme

By Jo Waller, on 4 May 2018

By Samantha Quaife and Maria Kazazis

Lung cancer is typically diagnosed too late; a major reason why it remains the leading cause of cancer death both in the UK and globally. Catching lung cancer early drastically improves survival, but often there are no symptoms in the early stages, or at least no symptoms that initially cause alarm.

Therefore, a national lung cancer screening programme is being considered in the UK. This would use a special type of CT scan with a lower dose of radiation (a LDCT scan) to screen for nodules in the lungs which could be early cancers. There is evidence from a large US trial that this decreases deaths from lung cancer among current smokers and former smokers aged 55-74 who have a significant smoking history. However, there are risks as well as benefits to screening and the UK are waiting for further European evidence.

One potential problem our research is trying to address is low uptake. For screening to work best, those taking part should be at high risk of developing lung cancer (usually due to a long history of tobacco smoking among other factors). Smoking is more common within socioeconomically deprived communities meaning that a greater proportion of adults are at high risk when compared with more affluent communities. However, in both Europe and the US, fewer smokers and individuals of a lower socioeconomic position, have taken part in screening when offered by research trials. But trial participation is different. What we don’t know is to what extent this problem might exist in the context of a national NHS programme.

In our newly published paper, funded by Cancer Research UK and the Medical Research Council, we surveyed 1464 adults aged 50-70 years as part of our Attitudes Behaviour and Cancer-UK Survey (ABACUS). We asked participants how likely they were to take part in screening following three hypothetical screening invitation scenarios. We also asked participants how much they worried about lung cancer, whether they thought the chances of surviving early stage lung cancer were good and whether they thought (again hypothetically) they would have surgery if screening found an early stage cancer. We compared current smokers with non-smokers on all these beliefs.

Most participants (97%) thought screening was a good idea and intended to be screened, regardless of their smoking status (>89% of current and former smokers). This is encouraging in principle, but intentions are not always the most accurate way of predicting actual screening behaviour. Indeed, we also found that smokers reported worrying more about lung cancer, and were less likely to think the chances of surviving lung cancer (when detected early) are good, or think they would opt for surgery (the most effective treatment for early stage lung cancer). It’s possible that these negative perceptions may deter smokers from screening. Importantly though, beliefs are modifiable. To optimise participation among those at high risk, we should communicate the screening offer in a way that minimises excessive worry, clearly explains the improvement in survival for early disease and dispels any misconceptions about surgical treatment.

Reference: Quaife, S. L., Vrinten, C., Ruparel, M., Janes, S. M., Beeken, R. J., Waller, J., McEwen, A. (2018). Smokers’ interest in a lung cancer screening programme: a national survey in England. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4430-6

Close

Close