Chinese people living overseas: dilemmas during COVID-19

By Xin Yuan Wang, on 30 March 2020

In the third week of March this year, the majority of my research participants in Shanghai were finally allowed to freely step out of their home after they had self-isolated under stringent quarantine rules for more than 50 days since the Chinese New Year. However, there is still no further official notice about when schools will reopen, and wearing face masks is still meticulously followed by the majority. Nevertheless, many believe the dark winter has gone, and things are gradually coming to life in mainland China.

The screengrab above shows an infographic circulated among older people on WeChat, illustrating the five significant signs which will indicate whether the crisis has passed:

1) There is an abundant supply of face masks;

2) All the nurseries have re-opened;

3) Medical professionals no longer wear protection suits;

4) “Liang hui” (The National People’s Congress and The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference) takes place once again;

5) The ban on international flights has ended

However, for millions of Chinese people living overseas*, there is still a long way to go, given that the pandemic is now raging outside of China with unexpected speed. In many societies, the Chinese diaspora were the first who started to wear face masks and avoid public transport at a time when most others saw no point in doing so. At UCL Anthropology, Chinese students showed great concern about the situation in London, most of them showing signs of anxiety at least two weeks before most other students. Before UCL decided to cease all face-to-face teaching on the 15th of March, I had received a collective request for ‘digital lectures’ from all the Chinese students on my course. Before this, it was these students who had been subject to racial and social discrimination.

Screenshot of news item about Chinese students who had suffered discrimination. This has been circulated widely among the overseas Chinese community. Source here.

Maggie, one of the students, puts it this way:

“Should I simply follow the Chinese government’s guild line as well as all my family and friends’ urge to wear masks and do self-isolating, which means I will be treated like an idiot in the UK, or try to follow the local mainstream that lives life as usual but feels so overwhelmed in the crowd?”

For these students, the sense that in the UK a lot of things were left to ordinary people’s discretion while in China there were rigorous regulations in place was itself a cause of anxiety.

Since the beginning of March, the overwhelming sentiment has been that ‘China is the safest place in the world’. Students, desperate to go home, were finding that the price of flights had gone up between three to five times what it normally was. At the same time, they were receiving endless WeChat messages to come home. There followed all sorts of stories about how they wore masks for the entire 20-hour trip and refused all food and drink until they got home.

An example comes from Ms. Chen, who managed to fly back to Shanghai on the 12th of March. When she landed, there were at least ten ambulance and police cars waiting on the tarmac. Passengers were then examined and those with a high temperature were taken to collective quarantine facilities or hospitals straight off the aircraft. The rest were not allowed to leave or take any public transport – even the use of the toilet was regulated, with passengers only being allowed to go if accompanied by airport staff in protective suits and masks. Ms. Chen needed to travel to a neighbouring city from Pudong airport. Along with a few passengers going in a similar direction, Ms. Chen was picked up by specific coaches and subsequently ‘handed over’ with extreme caution between different officials of varying levels, from city representatives (who were on standby at the airport 24/7) to district officers and finally, subdistrict officers. This continued until she finally arrived home.

The photo provided by Ms Chen of the flight she took. It is unknown who the author of the photo is, although the photo itself has been circulating online quite widely.

At 2 am, the officer responsible for the living compound (the party officer at the grassroots level) was already expecting her in front of her door. Upon entering her flat, Ms. Chen’s door was immediately sealed using paper strips. Every day, food would be sent to her door and she would be required to report her temperature twice a day via WeChat as well as receiving a regular check from a community doctor and getting her rubbish taken away. After this, her door would be re-sealed. On day two, a policeman came to install CCTV in front of her door. After 14 days of home quarantine, she would receive a nucleic acid test (one of the types of test that can detect the virus), and only upon receiving a negative result would her home quarantine end.

Ms. Chen thinks she is fortunate in that she was allowed to be home quarantined in the first place. More recently, Jing, 65, a previous research participant in Shanghai who is planning on travelling back to Shanghai from Australia, expressed concerns about her journey home. By that time, China had implemented an event stricter policy aimed at handling an increasing number of ‘internationally imported cases’, and anyone arriving from abroad would be transferred to collective city quarantine facilities for 14 days.

Photo taken by Jing: a subdistrict officer wearing a protection suit receiving passengers from the airport

Official photos of the Shanghai Pudong airport. Source here.

At the time of writing, China has reduced flights even further: The Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) has requested Chinese airlines to only maintain one route into each country and is limiting the number of flights to one per week, effective March 29. China has also suspended practically all foreigners’ entries into the country.

An additional factor when considering the dilemma of those living overseas is that most of them still take their news mainly from China, staying connected to their home country through their smartphones – the same phones that allow them to maintain a close connection to relatives and friends. All of the above contributes to the feeling of still ‘being at home’, which in turn implies a feeling of ‘not at home’ in these foreign countries.

“When you open WeChat, you only read good news about China and sensational, negative news about the rest of the world, and then there are all your Chinese contacts sending their urgent concerns to you as if you were living in hell.” – observes Yong, a UK-based Chinese professional.

Yong’s observation is not unfair. Recently, even the articles reflecting upon the death of the ‘whistle-blower’ Dr Li Wenliang had been censored on Chinese social media. Dr Li tried to issue the first warning about the virus outbreak in December last year but was accused of ‘spreading rumours’ by local authorities. He was subsequently exonerated after his death.

More fundamentally, between the UK and China, there are different attitudes in the state’s response to the virus. Things that would be taken as a gross invasion of individual freedom in countries like the UK are commonly appreciated as ‘care’ among the Chinese. It is this ubiquitous extreme forced ‘care,’ that results in Chinese people feeling much safer in China.

In colloquial Chinese, most commonly, people use the word ‘guan‘ to refer to all kinds of care. Still, another primary meaning of ‘guan‘ is ‘discipline’ and ‘control,’ and one can find the same character in ‘management’ (guan li). To say ‘adult children fail to take care of their older parents’ in Chinese would be ‘the children no longer guan their older parents’. Also, if one wanted to say ‘the Party clamps down on corrupted officials’, one would say ‘the party guan the corrupted officials’. “Guan is all about love“, as one of my research participants in Shanghai said.

Throughout China’s long history, emperors were always viewed as the head of a big family who takes care of the family members by guarding things closely and keeping them under control. On a related note, I recently wrote an article about why ordinary Chinese citizens generally welcome the Chinese social credit system. This ‘surveillance’ is perceived as a kind and responsible measure to take great care of good Chinese citizens.

The current crises are likely to become a further justification of the Party’s all-encompassing control of personal data. Once again, the smartphone is a key player here, since it provides the underlying capacity for tracking down close contacts of infected persons with the help of Big Data, something quite astonishing given that China is the world’s most populous country and yet has managed to control the spread of the virus.

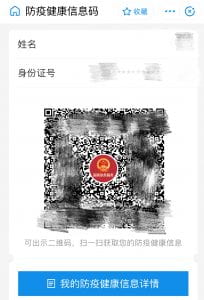

During the crisis, the majority of the population has adopted the smartphone-based ‘Health QR’ code, which is a real-time, big-data-fed personal health credit system which determines whether citizens have to be quarantined or can move around freely (see the photo on the left below). For many, the Health Code has become essential, serving as a personal health ID which allows one to enter office buildings and community facilities. It is not difficult to jump from ‘health credit’ to a more general social credit when members of the public already accept the concept of ‘individual credit’.

Health QR code provided by Alibaba, data provided by the General Office of the State Council, P.R.C.

Health QR Code for Shanghai residents

There are two key lessons here which also reinforce the commitment to anthropology. The first is to take note of the very different responses between countries and the way restrictions are implemented. To a large degree, these do seem to follow longstanding cultural differences. The second is to delve beneath this to ensure we provide an empathetic appreciation of ordinary people’s choices and dilemmas in such chaotic times.

* This blog post refers to people from mainland China.

Close

Close