“It’s kind of putting us in a difficult situation as students”: Responses to this year’s A Level Reforms

By qtnvacl, on 22 August 2017

Last week’s A level results day marked a number of milestones. Notably, this was the first year that students in England sat linear (also referred to as ‘tougher’) A levels; students studying one of the already-reformed A level subjects sat courses with little, or in most cases no, coursework and a final exam testing their knowledge of both years of the course rather than only the final year. There was plenty of analysis surrounding this – the headlines informed us that the reforms may have played a part in boys overtaking girls in top grades and that there was a drop in attainment for those subjects which have already been reformed, which includes all three sciences.

Missing from much of this analysis was any student opinion of these reforms – what did the young people affected by these changes think of them? Last winter, as part of a data collection cycle for the ASPIRES 2 study[1], we interviewed 51 Year 13 students from around the country ahead of their A level exams. We asked these students, and some of their parents, about their schooling and future plans. Although the A level reforms were not a planned interview topic, 10 of these students, and a small number of their parents, shared their thoughts about the changes – mostly in response to a question about the challenges faced by young people today.

Missing from much of this analysis was any student opinion of these reforms – what did the young people affected by these changes think of them? Last winter, as part of a data collection cycle for the ASPIRES 2 study[1], we interviewed 51 Year 13 students from around the country ahead of their A level exams. We asked these students, and some of their parents, about their schooling and future plans. Although the A level reforms were not a planned interview topic, 10 of these students, and a small number of their parents, shared their thoughts about the changes – mostly in response to a question about the challenges faced by young people today.

In this blogpost we share the emerging themes from these conversations, in order to shed light on student opinion of these part-introduced reforms. However, please note that due to the small sample size we recommend more in-depth research into this topic before drawing meaningful conclusions.

As the blog’s title (a quote from one of our students) indicates, many students felt pressured by the new reforms. The impact of this pressure upon mental health was not unexpected by some education experts; the “hastily reformed curriculum… created unnecessary stress and concern for pupils and teachers alike” said Rosamund McNeil from the National Union of Teachers ahead of last week’s results day.

The “memory game”

Some students disliked that the new linear courses required them to remember additional material for their A level exams. It’s “almost a memory game” said one student, Victoria1[2] (studying A level Maths, Politics, Design & Technology), who said that it felt like students were now “expected to recite something word for word… From two years ago, rather than just learn it, do it, learn it and then it would like stay there.” Worryingly, this was also cited as a reason to drop certain subjects, especially those seen as particularly content-based. For example, Louise (A level Psychology, Dance, Combined English) used the reforms as a justification for dropping Biology, her only STEM subject; “Um, I am pleased I dropped it, not necessarily because I didn’t enjoy it… there was just so much, but it was more, the fact was like how A levels are now structured – so I did all my AS stuff, did my AS exams, but for this year I’d have to remember everything from last year and then a whole new set of stuff.”

Another student added that this requirement to remember additional information may lead to decreased enthusiasm for, or interest in, some subjects; “I think because [the AS and A2 exams] have been stuck together, people are just losing focus over time… that’s definitely an issue. Like I know it’s definitely hard to stay motivated with what you’re doing” said Neb (A level Physics, Maths, Further Maths).

No room for mistakes

The reforms also meant that some students felt pressure not to ‘make a mistake’ in choosing or taking their A level options, as many thought that the reforms made it more difficult to drop, change or retake options. Two students we spoke to raised concerns that the reforms limited their access to the possibility of retaking exams, which will now only be available once, instead of twice, a year; “I prefer the old system where we did the AS papers and they counted towards the A2 and you could retake them” said Preeti (A level Physics, Biology, Chemistry, Maths). “There’s just so much stuff to remember, there’s so much content and you just feel so pressured to remember everything, and you get stressed out… if [students] did want to like resit they’d have to redo the whole year, so it’s a lot” said Celina1 (A level Psychology, Sociology, History), who was also worried that the A level changes meant that no suitable past papers were available to her.

Reforms come with uncertainty

Being the first cohort to experience these reforms was also something that played on the minds of the students and parents we spoke to; “changing the A Levels to being linear, it’s kind of put my year group in a slightly difficult situation” said Bethany2 (A level English Literature, Sociology, Applied ICT). This was seen not only from the perspective of students but also teachers; “the teachers haven’t really taught this type of course before” said Bethany2, something echoed by one student’s parent who called the changes “disruptive” and thought this year’s students had been put at a disadvantage as the first year group to experience the changes.

Strikingly, most students who raised the topic of the new A level curriculum with us expressed views that this year’s reforms contributed to the exam pressure they were already under. Whether this is something which will lessen as the reforms continue to be rolled out over the coming years remains to be seen. In any case, insights from our research suggest that the government, schools and parents must be aware that young people are concerned that the new A level curriculum places unwelcome additional pressure on students.

By Emily MacLeod, Research Officer on the ASPIRES 2 Project

[1] This was the fifth round of interviews with this cohort. The ASPIRES teams first started speaking to these young people and their parents when they were 10. For more information about, and findings from, this longitudinal project please visit: ucl.ac.uk/ioe-aspires

[2] Pseudonyms are used throughout, to protect the identity of all interview participants.

The Home of Science Capital

By qtnvacl, on 11 July 2017

The concept of science capital was first developed by Professor Louise Archer and team during the first phase of the ASPIRES project.

Since then, the concept of science capital has been developed by ASPIRES/2’s sister project (also headed by Professor Louise Archer), Enterprising Science. Researchers working on Enterprising Science have created tools to measure science capital and developed strategies for building science capital in primary and secondary schools as well as informal learning institutions such as museums.

This year marked the start of a new science capital-related project, YESTEM, a joint UK-US project funded by Wellcome Trust and the National Science Foundation developing new models and tools in support of equitable pathways into STEM.

You can learn more about science capital at our home page.

Meet our Director

By qtnvacl, on 16 June 2017

As the new Karl Mannheim Professor of Sociology of Education our Director, Professor Louise Archer, took part in a Q&A session.

Read about Louise’s role, and what her proudest academic achievement is, here.

ASPIRES 2 Research featured in Education and Employers Research Report

By qtnvacl, on 20 May 2017

Following the 2016 International Conference on Employer Engagement in Education and Training, where ASPIRES 2 Research Associate Dr. Julie Moote presented project findings on careers education provision, our research has been published in ‘Research for Practice: Papers from the 2016 International Conference on Employer Engagement in Education and Training’, edited by Anthony Mann and Jordan Rehill.

Our contribution to the paper presents findings based on data collected in the first data collection cycle of ASPIRES 2, when students were in Year 11, aged 15-16. Alarmingly, our data showed that careers education provision in England is not just ‘patchy’, but ‘patterned’ in terms of existing social inequalities. Our findings therefore indicated that schools are not only failing to provide careers education to all, but that the students most in need of this support are the least likely to receive it.

Watch Dr. Moote’s presentation here.

The full paper can be found here.

The ASPIRES Project Spotlight on careers education provision can be accessed here.

In an-depth analysis of our findings on careers education can be found here.

Are the white working-class an underrepresented group in science?

By qtnvacl, on 27 April 2017

By Lucy Yeomans, Doctoral Researcher on the ASPIRES 2 Project

Campaigns to improve diversity in science have often focussed on gender, with the lack of women participating in Physics being an ongoing concern within science education policy and practice. The work of ASPIRES has certainly made contributions to these debates, but also advocates a more intersectional approach to understand gendered, classed and racialised inequalities in science fields. Prior attainment has often been raised as the most reliable determinant of future science participation, however even when attainment has been taken into account students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to pursue science pathways than their peers. The government’s recent concerns regarding white working-class underachievement in education as a whole begs the questions: are the white working-class an underrepresented group in science? If so, how can we make sense of why this might be? Is it because, as has been suggested in policy discourse, they suffer from a deficit of aspiration? Do they simply lack the academic attainment to enable their future success in science?

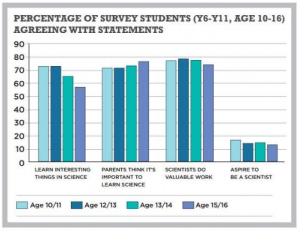

As a doctoral student working on the ASPIRES project my research aims to explore the sociocultural factors which may influence white working-class students’ future science participation. I am currently in the third year of my study, and having confirmed that white working-class students are indeed underrepresented in post-compulsory science fields, I have drawn on the ASPIRES longitudinal interview and survey data to investigate whether white working-class students are less likely to conceive science as being ‘for me’ and whether this is a consistent construct or something that changes over time.

As in the wider ASPIRES project, my analysis so far has led me to reject the ‘deficit aspiration’ discourse and move beyond the rationale of prior attainment as the sole important determinant of future science participation. I am currently exploring white working-class participants’ (now aged 18) histories of engagement in science outside of school both to determine their levels of ‘science capital’ and to see how they differ, or correspond, with students from different sociocultural backgrounds, including looking for differences in gender. The next step will be to look at participants’ aspirations in science and how they may change when students leave primary school and progress through secondary school.

Access to participants’ interviews dating from their final year of primary school through to their final year of compulsory education has provided unparalleled insight into the evolving values and dispositions of these white working-class students as they navigate various changes in themselves and their environments. Through this research I expect to provide some improved understanding of how the changes, and the differential strategies used by students of different sociocultural backgrounds to manage these changes, inform white working-class students’ non-choice of science. Widened access to higher level science subjects is important for citizens operating in an increasingly sophisticated technological world, while a diverse scientific workforce is important for economic prosperity and for reasons of social justice. I hope that my research will provide some useful and important new insights for policy and practice.

Lucy Yeomans, Doctoral Researcher on the ASPIRES 2 Project

ASPIRES 2 moves to the UCL Institute of Education

By qtnvacl, on 1 March 2017

Following the appointment of ASPIRES 2 director, Professor Louise Archer, to the Karl Mannheim Chair of Sociology of Education based in the Department of Education, Practice and Society at the UCL Institute of Education, the ASPIRES 2 project will be moving from King’s College London from 1st March.

Our longitudinal study, funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council, began with the ASPIRES project in 2009 at King’s College London’s School of Education, Communication (formerly the Department of Education and Professional Studies). Since 2009 our study into young people’s STEM and career aspirations has enabled us to track our cohort from primary, through secondary school and now, in our final round of data collection, at further education.

In the project’s eight years ASPIRES and ASPIRES 2 researchers have:

- tracked students’ aspirations from age 10 to age 18

- surveyed over 37,000 students

- conducted regular interviews with over 90 students

- spoken regularly with over 80 parents

- analysed over 600 hours of transcribed qualitative interviews

- visited schools across the country

Throughout the move our final round of fieldwork is ongoing, so look out for our emerging findings in the coming months.

We look forward to continuing our research at the IOE.

The ASPIRES 2 Team

Failing to deliver? Exploring the current status of career education provision in England

By qtnvacl, on 17 January 2017

Our newest project paper, ‘Failing to deliver? Exploring the current status of career education provision in England’, has been published in the Research Papers in Education Journal with Taylor & Francis.

The paper, written by project Research Associate Dr. Julie Moote and project Director Professor Louise Archer, investigates students’ views on careers education provision and their satisfaction with this provision.

The paper, which is open access, is available to read online and download here.

ASPIRES 2 in the Skills, Employment and Health Journal

By IOE Blog Editor, on 6 December 2016

Following a presentation by ASPIRES 2 Director Professor Louise Archer at Learning and Work’s Youth Employment Convention 2016 on 5th December, we wrote an article for the Skills, Employment and Health Journal.

The piece sets out our project findings in the context of social mobility, and how science has the potential to a powerful tool in promoting active citizenship. The key findings detailed are:

1. Lack of interest in science is not the problem

2. Careers provision is not reaching all students

3. Science Capital is key

4. Science is seen as only ‘for the brainy’ and ‘a man’s job’

Our recommendation is to change the system, not the students; we call for a review of both the stratification of science at KS4 and the longer-term desirability of A levels.

The full article can be found on the Skills, Employment and Health Journal’s website here .

(Why) is femininity excluded from science?

By IOE Blog Editor, on 18 November 2016

— Emily MacLeod

The lack of gender diversity within science is well documented and well researched. Many have attempted to pinpoint the reasons for the lack of women participating in science, and/or generate methods to solve the sector’s lack of diversity. However, whilst there remains a great deal of focus on the subject of Women in Science, discussion is lacking when it comes to the role femininity plays within this.

ASPIRES Book now out!

By IOE Blog Editor, on 10 October 2016

Our new book, based on the findings of the first phase of our project (ASPIRES), is now out. Understanding Young People’s Science Aspirations is by ASPIRES and ASPIRES 2 Director Professor Louise Archer, and ASPIRES Research Associate (now ASPIRES 2 co-investigator) Dr. Jennifer DeWitt. The book offers new evidence and understanding about how young people develop their aspirations for education, learning and, ultimately, careers in science. Integrating findings from ASPIRES with a wide ranging review of existing international literature, it brings a distinctive sociological analytic lens to the field of science education.

Close

Close