International Women’s Day: How gender equal is UCL’s student body?

By ucypsga, on 9 March 2018

On 6 February 1918, the UK’s Representation of the People Act extended the right to vote to almost all men, plus women who were over the age of 30 and able to meet minimum property qualifications. Ten months later, on 14 December 1918, 8.5 million women were able to vote for the first time.

Going back a further 40 years, in 1878, UCL became one of the first universities in England to admit women on equal terms with men.

This year, to mark these milestones in the march towards equality, UCL has been hosting a series of events and exhibitions. And here at the GEO, we thought it presented a great time to take stock of the progress we’ve made, and analyse in a little more detail just how well UCL is doing in terms of equality – as well as the higher education world more generally.

Steady increase in female students

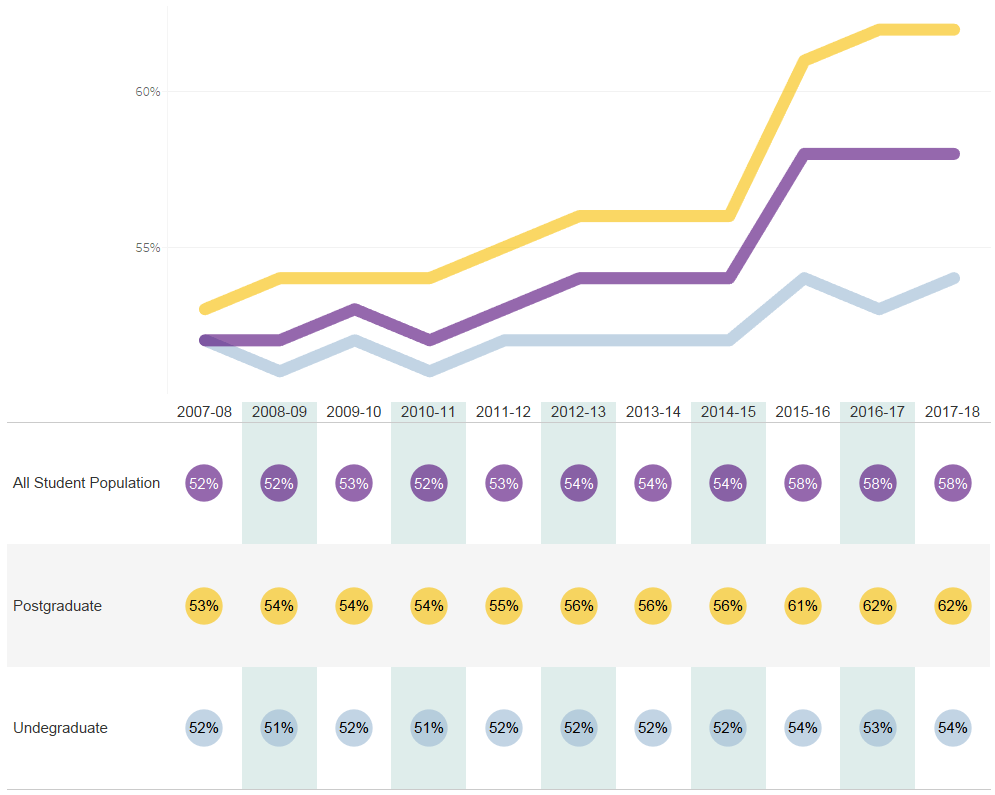

Taking a look at the gender data graph provided by GEO’s Strategic Data Manager Alejandro Moreno and pictured below, it’s clear that UCL admits more women than men at both post- and undergraduate level.

Since 2007, the overall figure has grown steadily, moving from a 52% female-heavy student population up to 58% in the current academic year.

While there are of course variations from faculty to faculty, the overall number of women studying at UCL is at its highest rate among postgraduate students. In 2017-18, for example, the percentage of female postgrad students is as high as 62%.

Record highs of women at university

The dominance of women at UCL is echoed across the wider UK higher education world. In 2017, record numbers of women in the UK went to university. According to a report in The Independent, the latest figures show that teenage girls are now over a third more likely to go to university than boys.

Data collected shortly before the current academic year showed that across the UK, 27.3% of all young men were expected to go to university this year, compared with 37.1 per cent of young women.

Clearly, the UK has come a long way since UCL first admitted women on equal terms with men. According to the BBC, the latest official figures show 55% of women entering higher education by the age of 30, compared with 43% of men.

Debate rages over the reasons behind this new high in the proportion of women in higher education, with everything from an exam system based on coursework to the underachievement of white working class boys suggested as factors. But taking a broad look at the higher education world indicates that the gender gap can’t simply be put down to a question of economics.

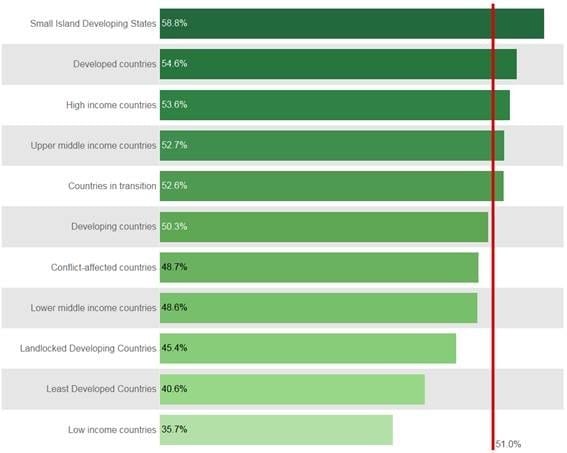

In fact, more data collection from Alejandro shows that small island developing states are the most likely to see a higher proportion of women in HE (58.8%) in the world, followed by developed countries at 54.6%.

Room for progress

Of course, there is still room for progress. Recent reports show that despite the dominance of women among student bodies, there are still only 27 women vice chancellors in the UK (six in the Russell Group), and only 24% of professors are women.

In addition, as UCL’s Vice-Provost International and Gender Equality Champion Nicola Brewer commented recently in her speech, ‘In praise of difficult women’: “I’m aware that it’s not always a binary choice. And increasingly I’m trying to think about equality through a more intersectional lens.”

Echoing this sentiment and speaking following the launch of a diversity report from the Royal Society of Chemistry last month, Lindsay Harding, senior lecturer at the University of Huddersfield, noted that there’s a fundamental issue with the collection of gender data.

“Gender data has a big limitation in that it’s collected in a binary way,” she said. “Recent surveys show that 0.4% of the UK population don’t identify with binary gender. We need to look at how we gather gender data to be more inclusive.”

Close

Close