Our latest update comes from Dr Tim Causer, the former coordinator of Transcribe Bentham who is now working on Bentham’s writings on Australia. Dr Causer has recently edited a new edition of ‘Memorandoms by James Martin’, a convict’s first-hand account of a daring escape from a penal colony in Australia in 1791. The only known copy of the manuscript was acquired by Bentham and is now held in UCL Special Collections.

‘Those of us researching the history of convict transportation to Australia are extraordinarily fortunate in terms of resources, as some of the most important have, for several years, been available digitally on an open-access basis. For instance, we can search colonial-era newspapers in the National Library of Australia’s Trove, or consult the Tasmanian convict records, a body of material unique in its detail about the tens of thousands of ordinary people transported to Van Diemen’s Land.

As a callow undergraduate at the University of Aberdeen, making a first foray into Australian history fourteen years ago, such resources were the stuff of dreams. The university library’s holdings on Australian history were largely limited to landmark secondary texts such as Russel Ward’s The Australian Legend (1958) and A. G. L. Shaw’s Convicts and the Colonies (1966). The most recent work we had to hand was almost two decades old: Robert Hughes’s blockbuster, The Fatal Shore (1986). Hughes’s brilliant, terrible book is beautifully written, but is ultimately frequently misleading. But a major strength of The Fatal Shore’s was its use of convict narratives, giving it an immediacy rare in many earlier histories which relied heavily upon parliamentary papers and official correspondence.

Convict narratives fall into two main types. The first, and most common, are those published in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, during or around the period in which convicts were transported to the Antipodes. For instance, two of the most well-known are Martin Cash’s The Bushranger of Van Diemen’s Land (1870) and Mark Jeffrey’s A Burglar’s Life (1893), both of which were ghost-written by the former convict James Lester Burke.

Of course, published narratives such as these present issues of interpretation. How much of Cash’s autobiography is authentically his voice, and how much is that of Burke? Ghost-writers often sanitised their subject’s life into a redemption parable, walking the fine line between titillation while still seeking to attract a respectable audience. Those narratives written by the few transported for political offences—male, middle-class, well-educated authors—are unrepresentative of the experiences of the majority of convicts. There is also a racial and gender imbalance, with the overwhelming majority of narratives dealing with the lives of white convict men—Reverend James Cameron’s partly-fictionalised biography of the Spanish transportee, Adelaide de Thoreza, is a rare exception.

The second type of narrative exists only in manuscript. They are often more exciting to deal with: they were not written for publication, do not have to meet the conventions of any genre, and are often more revealing, explicit, and subversive. For instance, the Irish convict Laurence Frayne’s narrative is a graphic account of his punishment and contains a sustained character assassination of James Morisset, a commandant at the Norfolk Island penal station during the 1830s, which would never have been fit to print.

Memorandoms by James Martin is one such unpublished manuscript which, thanks to UCL Press, is now available in open-access for the first time. The Memorandoms tells the story of the most famous of all escapes from Australia by transported convicts, that led by William and Mary Bryant. On the night 28 March 1791 the Bryants with their two infant children, James Martin, and six other male convicts stole a fishing boat and sailed out of Sydney Harbour and out into the Pacific. They reached Kupang in Timor on 8 June, though were subsequently identified as escaped convicts and the survivors were shipped back to England to face trial—where James Boswell lobbied the government for their release.

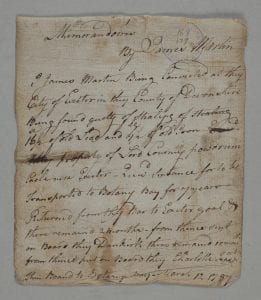

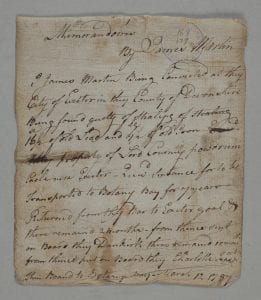

First page of Memorandoms by James Martin, UCL Special Collections, Bentham Papers, Box CLXIX, fo. 179

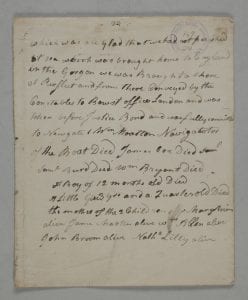

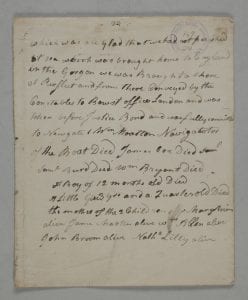

Final page of Memorandoms by James Martin, UCL Special Collections, Bentham Papers, Box CLXIX, fo. 201

The group’s 69-day, 3,000-mile journey has been the subject of two televisions series, poetry, novels, and innumerable history books, with a focus on Mary Bryant. Yet the modern historical accounts are frequently unsatisfactory and derivative; what then, the reader might wonder, could be said about this story that has not been said so many times before?

Quite a bit, it turns out. Memorandoms by James Martin is the only extant first-hand account of the escape, and it provides a fresh perspective to this often formulaically-told tale. Despite the Memorandoms being spare and prosaic, it provides a sense of the hardship of the journey, the terror of those in the boat as it is pummelled by storms and churning seas, and of the party’s fascination and fear in their encounters with Indigenous Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. The Memorandoms also strikingly reveals just how far some modern historians have departed from the historical record when telling the story.

Memorandoms by James Martin is also important in a second sense: it is the only known narrative written by a member of the first cohort of convicts sent to New South Wales with the First Fleet 1788. The Memorandoms was acquired at some point by one of Britain’s great philosophers, Jeremy Bentham, one of the first and most influential critics of transportation to Australia. The vast Bentham archive is, of course, held in UCL’s Special Collections, and the Memorandoms is but one of the many jewels in the College’s collections.

Now, thanks to UCL Press, the Memorandoms manuscripts are available for the first time, and for free; readers can now access the original narrative for themselves, rather than mediated by some rather dubious historical accounts. The colour reproductions bring the document to life in a way which would not otherwise be captured by publishing a transcript, and I am inordinately grateful to UCL Press for bringing the Memorandoms out in this way. My younger self in Aberdeen would have been thrilled to have had a resource like this to hand, and I hope that those who today may not have ready access to unpublished narratives like the Memorandoms will be equally pleased.’

Close

Close