Summer school: Technology and Change in Higher Education

By Clive Young, on 20 July 2013

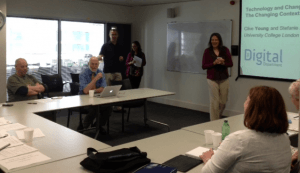

Last week with colleagues Martin Oliver and Cat Edera from the Institute of Education (IoE) Stafanie Anyadi and I ran a very successful summer school entitled ‘Technology and Change in Higher Education’. Both the IoE and ourselves have related projects under the JISC Digital Literacies programme and we were keen to explore some of the issues around emerging practices, roles and identities related to the changing technological environment.

Last week with colleagues Martin Oliver and Cat Edera from the Institute of Education (IoE) Stafanie Anyadi and I ran a very successful summer school entitled ‘Technology and Change in Higher Education’. Both the IoE and ourselves have related projects under the JISC Digital Literacies programme and we were keen to explore some of the issues around emerging practices, roles and identities related to the changing technological environment.- Authority had to be self-generated instead of being inherent in the job role

- Individuals had to create their own networks of influence.

- Professional development and career progression routes were less clear

- The boundary-jumping aspect may be ‘transgressive’ and challenge institutional ideas of identity and affiliation

- It might be difficult for colleagues and the institution to relate to fluid roles and recognise individual expertise

- This may result in border or ownership issues of issues that can be manifested as barriers

- Recruitment and induction into these ‘personally-constructed’ roles can be another problemThe group noted that restructuring if well implemented could be way of providing a ‘snapshot’ of these dynamic changes and route for the institution to accommodate them.

There were many positives. Such adaptive roles could help students navigate though existing ‘chains of support’. The importance in this respect of the Teaching or Departmental Administrator was mentioned several times. Technology could play a large role in providing a breadth of support for students and staff but often a human ‘broker’ was still much appreciated.

There were many positives. Such adaptive roles could help students navigate though existing ‘chains of support’. The importance in this respect of the Teaching or Departmental Administrator was mentioned several times. Technology could play a large role in providing a breadth of support for students and staff but often a human ‘broker’ was still much appreciated.

Close

Close

JISC

JISC