The Church of St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel: part two

By the Survey of London, on 1 July 2016

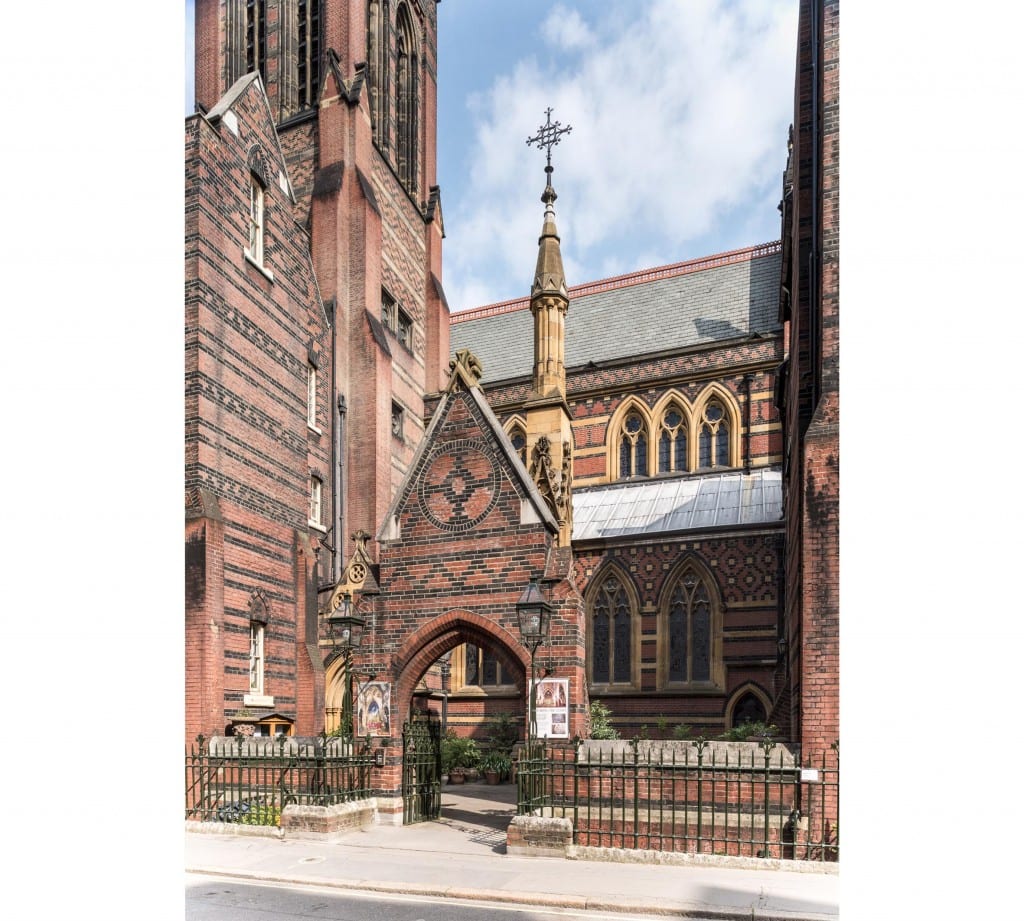

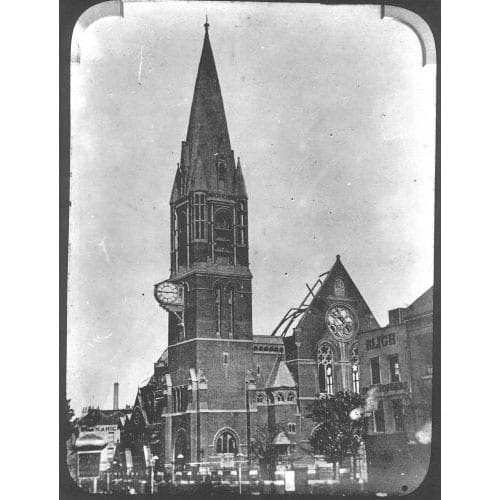

In 1873 an inspection in advance of an intended redecoration led to a condemnation of the seventeenth-century church of St Mary Matfelon as structurally unsafe (see earlier post). The parish reluctantly geared up to spend £4,000 on essential repairs. Then, in June 1874, Octavius Edward Coope came to the rescue. Coope was a wealthy brewer, a founder of Ind Coope & Co. in Romford in 1845, which firm expanded to Burton-on-Trent in 1856. He had been an MP in 1847–8, but was unseated on grounds of bribery. After a long interval he was again elected to Parliament as a Conservative MP for Middlesex in 1874. With that newly acquired status, Coope stepped forward claiming to be a Whitechapel parishioner – Ind Coope & Co. had offices and a depot on the west side of Osborn Street. Coope himself lived in Essex and, when in London, on Upper Brook Street in Mayfair. He offered to pay up to £12,500 towards a new church, presenting plans by his architect nephew, Ernest Claude Lee, who had been a pupil of William Burges’s, for a red-brick and stone-dressed High Gothic Revival building to seat 1,400. The offer was initially accepted with great relief and joy, but Coope had soon to defend the proposed use of red brick, averring, wrongly, that ‘our great church architect Street invariably uses it’. [1] In fact, for comparative inspection a Vestry committee turned to James Brooks’s recent red-brick churches in Haggerston, St Columba and St Chad. This committee was led by the Rev. James Cohen, a converted Jew who had been Whitechapel’s rector since 1860; it was subsequently spearheaded by Augustus William Gadesden, a sugar refiner. They were not impressed, convinced in their dislike of red brick, and anyway keen to have a larger church. Overall costs were estimated to be about £6,000 more than Coope was offering. Cohen’s committee concluded in September, with diminished alacrity, that ‘it is expedient that the offer of Mr Coope be accepted.’ [2] Rebuilding began in 1875 when Cohen was succeeded by the Rev. John Fenwick Kitto. Work was completed in October 1876 and there was a consecration in February 1877. The upper stage of the tower and spire followed in 1878. The estimated total final cost had risen to about £30,000 of which it was later said around £10,000 came from public subscription, the rest from Coope.

The Church of St Mary Matfelon was rebuilt with a tall spire in 1875-8, but it had to be largely rebuilt again after it was burnt out in 1880 (The East of London Family History Society, reproduced via Wikimedia Commons).

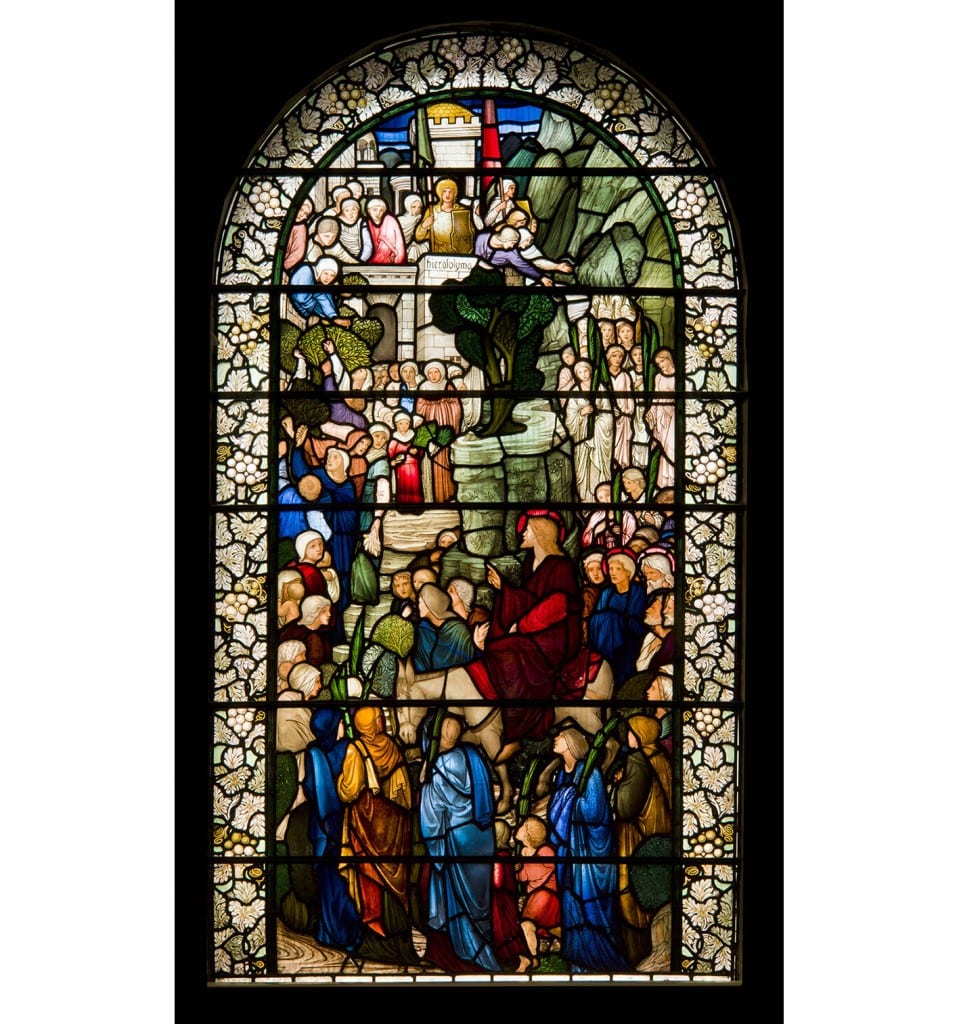

The large brick church comprised a nave and aisles, a round-apsed chancel, a baptistery under a west gallery and a three-stage north-west tower with an octagonal spire and corner turrets rising 175ft in all, sited so as to be prominent on the main road. It extended further west and south than had its predecessor and was set less squarely to the road, to minimise disturbance of the graveyard and avoid southerly ground that was only leasehold. While adhering to red brick, Lee had amended his plans. The church had only 1,250 sittings and omitted a full-height north transept in favour of a gabled organ bay at the east end of the north aisle. An unusual feature, reflecting the local evangelical mission, was an external pulpit, placed on a staircase turret at the north-west corner of the nave. There was a large ‘church room’ to the south-east in which relics from the old church were displayed. The interior had ornamentally carved Bath stone dressings to naked brick surfaces (perhaps intended for decoration), Minton floor tiles and a ceiled wagon-vault, a form chosen for auditory reasons, ill-advisedly as the building had very poor acoustics. The old clock and bells were reset. Lee deployed thirteenth-century style details and himself designed fittings including the pulpit, lectern, font and a mosaic apse floor, executed by Burke & Co. of Regent Street. Horatio Walter Lonsdale, Lee’s brother-in-law, supplied stained-glass windows. Stone carving was by Thomas Earp of Lambeth.

View of the interior of the 1876 church, looking towards the chancel (Building News, 8 September 1876).

This church was short-lived, suddenly gutted by fire on a summer’s Thursday afternoon, on 27 August 1880. Flames in the organ chamber swept up the organ pipes into the timber roof. The tower survived. Kitto and Gadesden led an approach to Coope, still an MP, who undertook to use his influence to secure insurance cover of £16,800 and to stump up further rebuilding costs. The acoustical shortcomings of the destroyed interior led him to make replacement conditional on a redesign by nephew Lee. The church was rebuilt in 1881–2 on the same plan, but with a polygonal apse and an open pseudo-hammerbeam roof beneath a lower ridge which did bring acoustical success. The nave west wall was given three windows in place of two, and there were other detailed variations that favoured a style more characteristic of the fourteenth century. The interior was yet more richly sculpted than its predecessor, and this time lavishly decorated with stencilling that shows the influence of Burges. Lonsdale supervised painting and glass.

The church was gutted by firebombs in 1940 (Historic England London Region).

An alabaster reredos intended since 1878 was at last made in 1886–7 as a memorial to Coope. Carved by Earp, it represented the Last Supper and the Tree of Jesse, and stood in front of stencilled decoration of the early 1880s by Lonsdale that included large angels for the Twelve Gates of the Heavenly Jerusalem.

Rebuilds notwithstanding, church attendance declined. It was estimated in the early 1880s to be around 1,500 across Sunday services, the main impediment being what the Rev. Arthur James Robinson called ‘the old story of indifference’. [3] Yet this was among the best attended of East London churches, with fully choral services and psalms chanted morning and evening. By 1884 Robinson’s team included two Missioners to Jews, the Rev. J. H. Bruhl and the Rev. A. Bernstein. The open-air pulpit was in regular use, and by the 1890s and well into the twentieth century special services were conducted for Jews in Hebrew and German, with sermons preached in Yiddish to congregations of up to 500. A last notable rector was the Rev. John A. Mayo, who gave the first ever radio sermon in 1922.

St Mary’s Church was gutted once again, this time by fire bombs on 29 December 1940. The ruined shell of the building was cleared in 1952.

Nave of the church in 1941 after bomb damage (Historic England London Region).

References

- Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, L/SMW/A/1/1

- THLHLA, L/SMW/A/1/1

- Lambeth Palace Library, FP Jackson 2, f.513

Close

Close