The Tilbury Shelter

By the Survey of London, on 17 April 2020

During the Blitz in 1940–1 a Whitechapel building, the Commercial Road Goods Depot, housed the East End’s single biggest bomb shelter. The history of what was known as the Tilbury Shelter seems timely, if only as a reminder of how different that crisis was from the one we are presently living through. What follows is based on research and text prepared for the Survey of London by Rebecca Preston. We would like also to acknowledge help from Robert Thorne, Tim Smith and Peter Kay.

Commercial Road Goods Depot from the north, c.1905 (© Museum of London/PLA Collection)

Commercial Road Goods Depot from the south, c.1905 (© Museum of London/PLA Collection)

The Commercial Road Goods Depot was a behemoth of a building that extended from the Commercial Road near its west end as far south as the viaduct of the London and Blackwall Railway, beside Cable Street. It was built in 1884–7 by the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway Company as a receiving and forwarding depot for merchandise dealt with at the East and West India Dock Company’s Tilbury Docks, which opened in 1886. The premises comprised ground-level vaults with viaduct-level sidings, a shunting yard and a branch line, and a goods station below the colossal warehouse. It was all demolished in 1975.

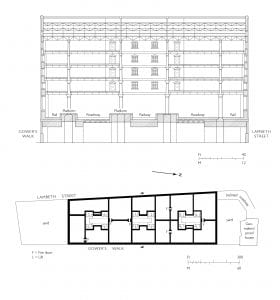

Commercial Road Goods Depot, plans at street-level (left) and upper rail-level (right) (drawn by Helen Jones for the Survey of London based on drawings by Tim Smith)

The London, Tilbury and Southend became part of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway Company (LMS) in 1923 as part of the ‘grouping’ or reorganisation imposed on private railway companies following the experience of government-run railways during the First World War. The lower levels of the Commercial Road goods depot served as general stores. The warehouse above was bonded and used by the Port of London Authority (PLA), the public trust that succeeded London’s private dock companies in 1909, as vast tea stores containing 78,000 chests.

Bulking tea for the PLA in the Commercial Road warehouse (from William Ukers, All About Tea, 1935)

In April 1940 the LMS agreed to the use of the Commercial Road Goods Depot as an air-raid shelter, provided Stepney Borough Council scheduled sufficient wardens to work under the company’s police, and that notices prohibiting smoking were put up in English and Yiddish. Initially the plan, probably a temporary measure, was to create two adjoining shelters, one for LMS personnel and a second ‘PLA Shelter’, above, for 1,400 members of the public. There were fears that ‘people caught in the streets would rush for this shelter as they did during the last war’.1 In preparation, the PLA’s engineers, Rendel, Palmer & Tritton, oversaw the bricking up of lower windows. However, when Stepney Council proposed using both the PLA and LMS sections as an official public air-raid shelter, the lower LMS section was refused approval by the Ministry of Home Security because it would involve ‘dangerously large concentrations of people in one shelter and because the Railway Company insisted that the roadway through the LMS sections be kept open for traffic’.2

Commercial Road Goods Depot, cross section looking south and typical warehouse floor plan (drawn by Helen Jones for the Survey of London based on drawings by Tim Smith)

The LMS Chief Engineer, R. C. Cox, noted that should the building be hit by a large bomb there was ‘a rather large calamity factor’, but that this was a necessary risk in the absence of other shelters in the area. In early September 1940, when the night raids of the Blitz began, the London Civil Division Region Officer told the Stepney Air Raid Precautions (ARP) Controller that ‘we must face facts as they are: this is not a public shelter but large numbers of people are using it as such and we cannot keep them out in present circumstances’.3 The LMS Goods Manager then agreed that about two-fifths of the low-level depot, the northern parts, could be used as a shelter under Stepney’s auspices with police protection, especially at Hooper Street, to keep out crowds.

The public, however, took possession of both the official (PLA) and unofficial (LMS) parts, thereby creating London’s largest air-raid shelter, which quickly became known as the Tilbury Shelter. Stepney was told that it must accept the situation and install sanitation. Works undertaken through Rendel, Palmer & Tritton were held up by labour shortages and were not complete in the official shelter until at least December. They eventually included bunks, lights, WCs, canteen facilities and medical supervision. When a head count was first taken in October 1940, some 8,000 people were found across both sections of the shelter. It was reported that on most nights the shelter held 14,000, thronging on a rainy night to form a ‘grim haven of 16,000’.4 There might have been exaggeration, but even so, in December official sources counted 4,244 people sheltering in the unofficial (LMS) lower-depot section, which remained ‘bare of amenities except hessian screened chemical closets’.5

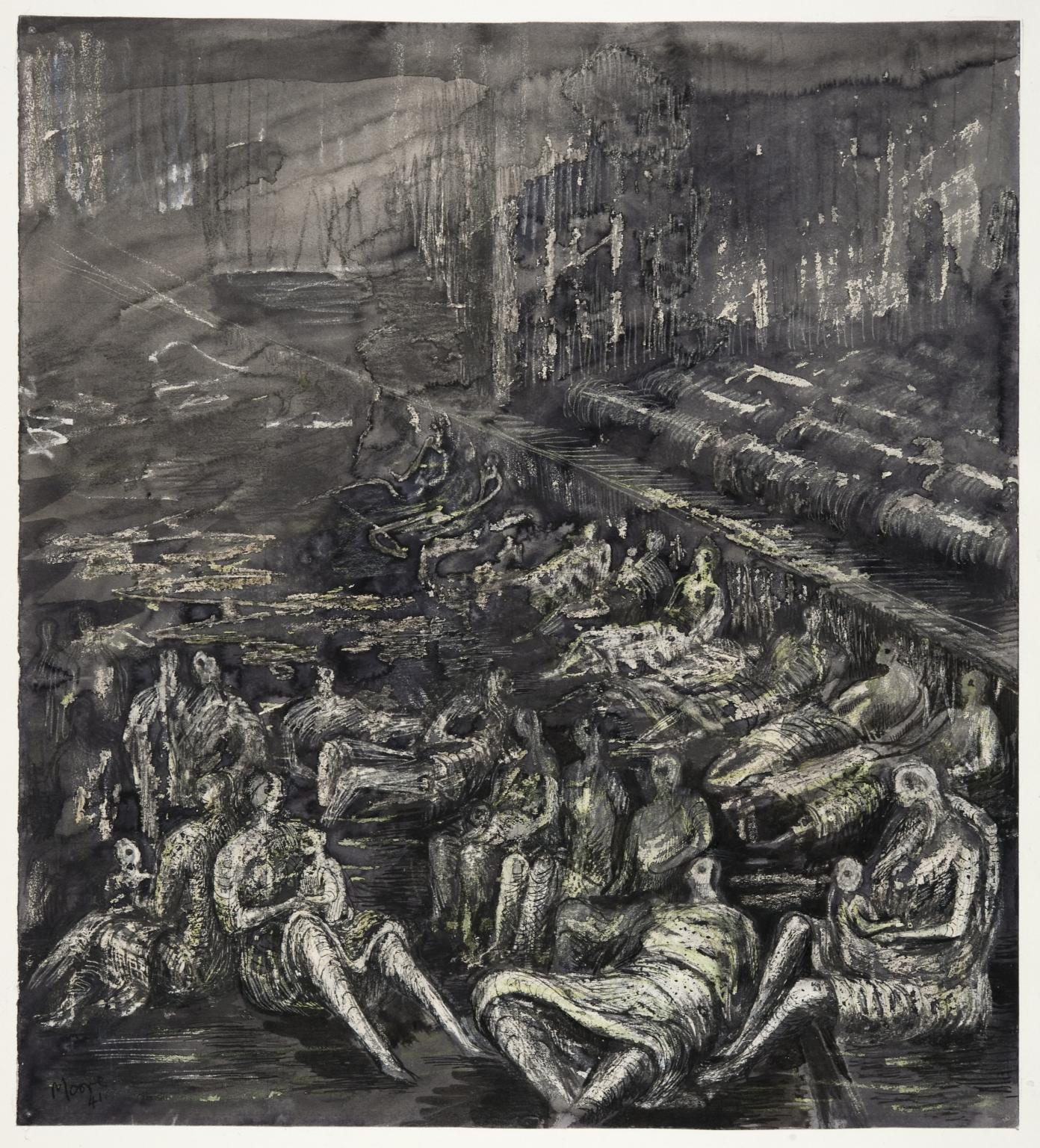

Henry Moore, ‘A Tilbury Shelter Scene’, 1941 (© Tate Gallery, presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N05708, CC-BY-NC-ND)

This unofficial shelter was managed internally by the Communist Tilbury Shelter Committee, the leading organisers of which in its early years appear to have been its Secretary, a Mr Neidle, and Miss M. Ackerman, the Honorary Secretary, who gave her address as 153f Back Church Lane. To the PLA Police, which held jurisdiction at the Tilbury Shelter, the mass of people in the unofficial section in particular presented the threat of unrest whipped up by political agitators. The social research organisation, Mass Observation, sent observers to report on life in the shelter, ‘to make a complete study of the sociology of the largest underground concentration of humans yet known’.6 It noted that the efforts of the PLA Police to prevent the sale of the Daily Worker were usually outwitted by the occupants, ‘by no means all of whom are Communist sympathisers’, on freedom-of-speech grounds.7

Edward Ardizzone, ‘Shelter Scenes’, 1941 (Imperial War Museum, Art.IWM ART LD 1091. © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/497)

Bunks were installed in 120 triple tiers in the PLA or warehouse section of the Tilbury Shelter in late October 1940. Within a month the vaults of the unofficial LMS or goods depot section had also been ‘fully bunked’.8 Nina Hibben, a Mass Observation worker, recorded that ‘The first time I went there, I had to come out, I felt sick. You just couldn’t see anything, you could smell the fug, the overwhelming stench … there were thousands and thousands of people lying head to toe, all along the bays and with no facilities … the place was a hell hole, it was an outrage that people had to live in these conditions’.9 Despite such accounts, it seems that a kind of order prevailed as necessary routines were established. Life in the cavernous interiors of the Tilbury Shelter was depicted by Henry Moore, as an official war artist, by Edward Ardizzone and Feliks Topolski, as Civil Defence artists, and by Rose Henriques, a local resident and philanthropist.

Rose Henriques, ‘Sleepers’, Tilbury Shelter, 1940 (© Museum of London)

Both sections of the Tilbury Shelter were ticketed and monitored by the police, the official part accessed from Commercial Road and the unofficial part, now cut off by a brick wall, from Hooper Street. Closure of the unauthorised part of the warehouse, if tickets for other shelters were provided, was pursued and resisted in early 1941. Colin Penn, an architect with Communist sympathies, appears to have been to the fore among five architects from the Association of Architects, Surveyors and Technical Assistants who compared the Tilbury Shelter with alternative accommodation. On finding that the majority was less safe than the unofficial LMS section, the architects refused to recommend dispersal and occupants broke down the dividing wall. The police prevented a subsequent meeting, at which the architects were due to speak, called in protest against the eviction of the remaining occupants, which now numbered between 1,200 and 4,200 depending on the severity of raids. Public resistance to evictions and closure of the unofficial shelter continued. By May 1941, however, after the last major attacks of the Blitz, the unofficial sections were ‘not of course used at all now’ and were soon taken over as an official shelter in readiness for further bombing.10

There were still rumblings of discontent during 1942 and 1943, when low numbers of occupants were recorded. Eleanor Roosevelt visited the Tilbury Shelter with King George VI in October 1942. Other interventions were made by Rear-Admiral the Rev. A. R. W. Woods, Chaplain of the Red Ensign Club (sailors’ hostel) on Dock Street. In November 1944, a deputation from the Hindustani Markaz (Indian Centre), 14 White Church Lane, was received by the Ministry for Home Security, the Stepney ARP Controller and the High Commissioner for India. It complained of offensive behaviour, that officials had on numerous occasions insulted members of the local Indian community in the shelter or prevented their entry on racist grounds.

Commercial Road Goods Depot from the south-west c.1970 (photograph by Dan Cruickshank)

Meanwhile the warehouse had itself been bombed. In early November 1940 a direct hit destroyed practically all of the roof and much of the top floor. This caused the PLA to wind up use of the building as a tea warehouse. Part of the warehouse was taken over by the Ministry of Supply and the US Army, which formed a large canteen at the north end. By 1946 the US Army had left, the Ministry of Supply was storing ‘portable house’ or Prefab parts, and the PLA had returned with tea. The vaults and ground floor once again became an LMS goods depot. The depot ceased operations in 1967 and demolition followed in 1975. The site was redeveloped for the National Westminster Bank as a computer centre. In recent years it has once again been redeveloped with tall blocks of housing.

Former Commercial Road Goods Depot hydraulic pumping station, Hooper Street, view from the west in 2019 (photographed for the Survey of London by Derek Kendall)

The only substantial surviving reminder of the railway goods-handling complex is its former hydraulic pumping station on Hooper Street, which was converted to office use in 2002–4.

1 – The National Archives (TNA), HO207/860

2 – Ibid

3 – Ibid

4 – Illustrated, 5 October 1940, p. 14

5 – TNA, HO207/860

6 – University of Sussex Special Collections, Mass Observation Archive, 486, Sixth Weekly Report for Home Intelligence, November 1940

7 – University of Sussex Special Collections, Mass Observation Archive, 431, Survey of Voluntary and Official Bodies during Bombing of the East End (RF/NM), September 1940

8 – TNA, HO207/860

9 – As quoted in Gavin Weightman and Steve Humphries, with Joanna Mack and John Taylor, in The Making of Modern London, 1983 (2007 edition), p. 260

10 – TNA, HO207/860

Colouring London

By the Survey of London, on 6 April 2020

Many of our readers will already be familiar with Colouring London, a map-based crowdsourcing platform designed to collect information on every building in the capital. We would like to share a blog post previously published to coincide with the launch of Colouring London in October 2019, in case any of our readers are looking for an interesting and rewarding distraction during these difficult times. Over the last six months Colouring London has collected large amounts of data about buildings in Greater London, and welcomes contributions from the public. This blog post offers some guidance on contributing to Colouring London by searching for data in the Survey of London series, an essential source for information about the city’s buildings and places.

Colouring London has been developed by the Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), part of the Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment at University College London, with funding from several academic and government organizations. The Greater London Authority, Historic England and the Ordnance Survey are core partners. The Survey of London is one of the project’s collaborators, offering advice on how to incorporate historical detail and sharing data from current research in Marylebone, Oxford Street and Whitechapel.

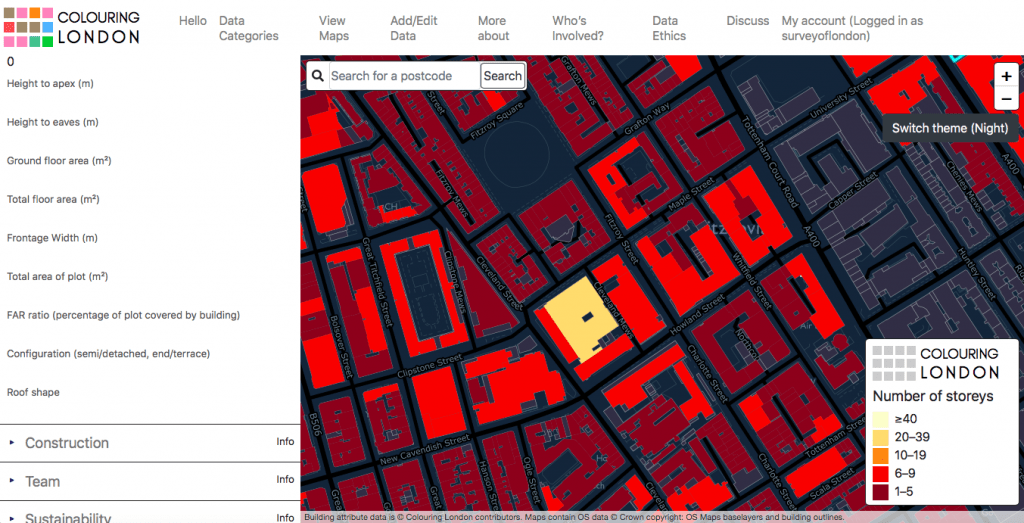

The Colouring London website, showing the Greater London study area

The Colouring London website, showing building age data in Camden

Colouring London has been designed to collect and visualize information about the built environment, inviting participation from any and all. The website provides a free knowledge exchange platform for data relating to all of the capital’s buildings and structures. As users contribute data, the footprints of individual buildings are colour-coded instantly to build legible maps about the city. In addition to submitting information, reading and interpreting the maps, users will be able to download the data. The website is currently in the stages of testing, which makes your involvement and feedback all the more important.

Polly Hudson, a researcher at the Bartlett and the instigator of Colouring London, has designed the website to harness information on building age, characteristics and lifespans. Data on the built environment is currently incomplete, fragmented and inaccessible, as organizations are slow or reluctant to release information to the public. The difficulty of collecting information about buildings and places is at odds with its inherent value. The Survey of London traces its beginnings to the Arts and Crafts architect, designer and social thinker Charles Robert Ashbee, who believed that to mark down a record of the historic environment is an essential and enriching public good. In the present day, accurate and comprehensive data about the city is also instrumental for urban analyses that contribute to research on significant issues, from sustainability to the housing crisis. These data also feed into scientific research on the reduction of energy use through the adaptive reuse of buildings and the use of predictive models relating to the vulnerability and resilience of cities in the future. For this type of research to be successful, knowledge needs to be converted into numerical data.

In the long term, there are plans for Colouring London to collect, store and visualize a broad spectrum of data relating to the built environment, spanning twelve categories such as land use, building type, designer and constructional details. For the initial testing phase of the project, a smaller number of categories were launched, including location, age, size and shape, planning and ‘like me’. Type and sustainability are now available for editing, while a land use category is set to become live soon.

Location

Location: This category covers the basic but essential data required to locate buildings accurately, such as address and coordinates. The colours on the map indicate the percentage of data collected. This screenshot shows that the locational information for King’s Cross Station and St Pancras Station is almost complete, whereas other buildings in the neighbouring streets are still waiting to be coloured in.

Age

Age: This section includes estimated construction date and façade date, with options to add sources and links. This screenshot shows All Souls Church, Langham Place, covered in the Survey of London’s South-East Marylebone volumes (published in 2017). If you have used the Survey’s volumes to find construction dates, please use the drop-down box to mark ‘Survey of London’ and include a link to the online version.

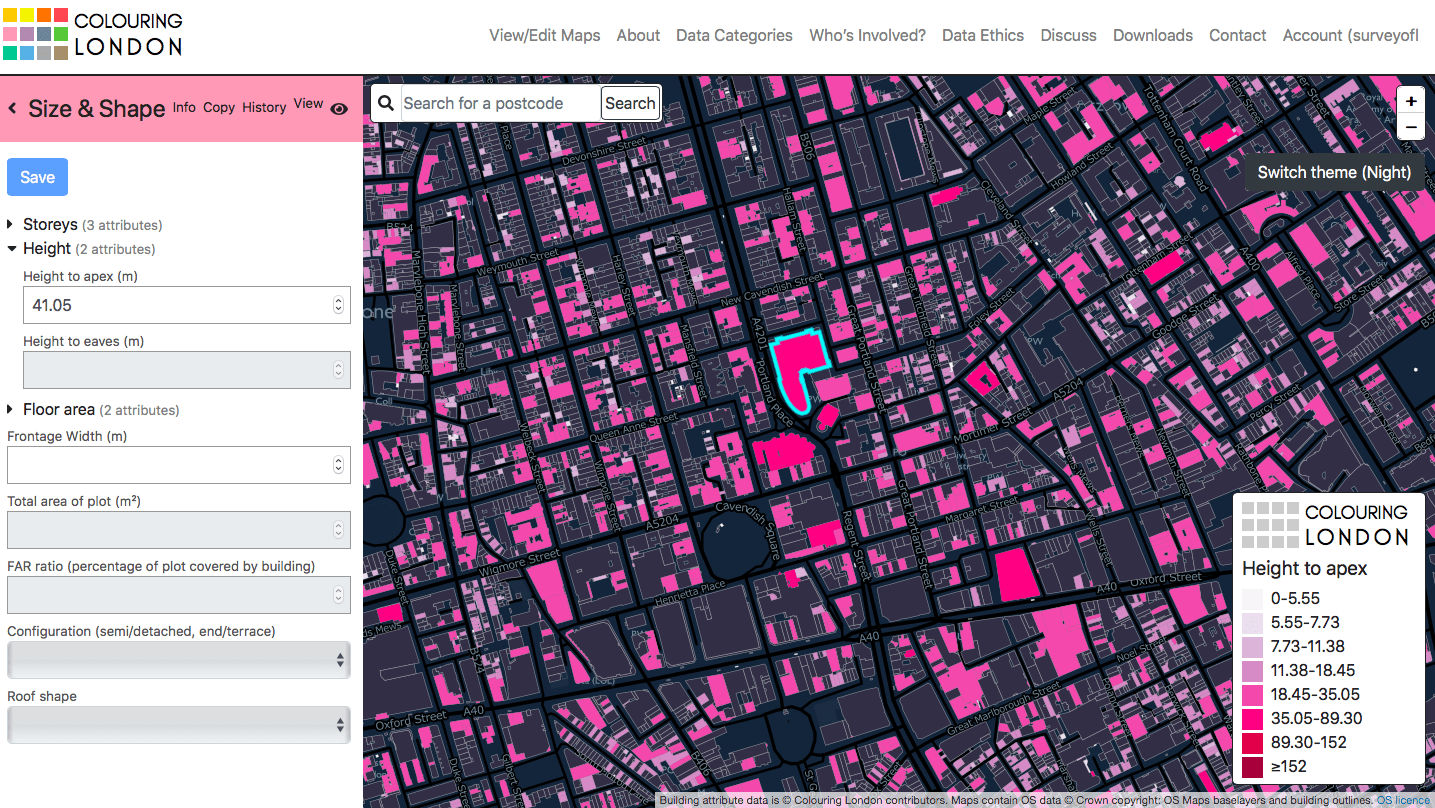

Size and shape

Size and Shape: This category relates to the form of the building, including the number of storeys, height and area. This screenshot shows Broadcasting House and its surroundings.

Planning

Planning: This category links the building to conservation areas, local lists and the National Heritage List for England administered by Historic England. This screenshot shows buildings which are located in conservation areas around Aldwych and the Strand.

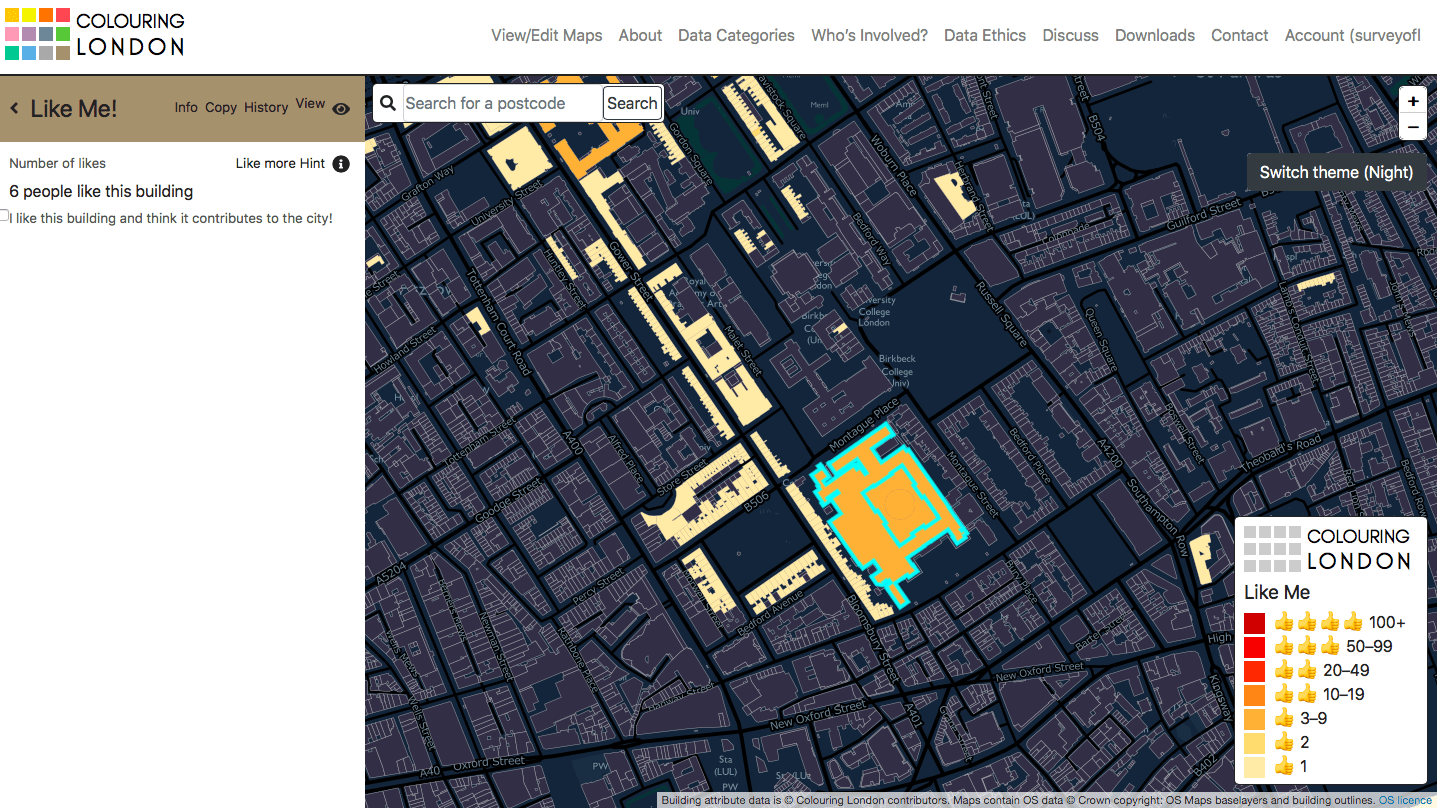

Like me

‘Like Me’: Designed to welcome positivity and inclusivity, the ‘like me’ function is a tick-box inviting users to pinpoint buildings that are admired and thought to contribute to the city. This screenshot shows the British Museum and Bedford Square.

Type

Type: This category covers building type, focusing on original form and use. This screenshot shows a former terraced house in Varden Street, Whitechapel.

Sustainability

Sustainability: This recently released category collects information about the sustainability and energy performance of buildings, including BREEAM ratings, EPC ratings and significant retrofits. This screenshot shows the National Gallery and its surroundings.

Since its beginnings in 1894, the Survey of London has amassed a wealth of information about the city, its districts and buildings. Fifty-two ‘main series’ volumes, which generally cover historic parishes, and eighteen monographs on individual sites of particular interest have been published, with the next ‘main series’ volume on Oxford Street expected to follow in Spring 2020. The hallmark of the Survey of London series is accessible and readable writing, based on a combination of detailed archival research, secondary sources and field investigation. The volumes contain a vast amount of reliable information – data, essentially – relating to the construction, form and evolution of buildings over time. All of these data may be uploaded to Colouring London.

It is possible to sign up to the Colouring London website within a few minutes, and start colouring building footprints immediately by adding data. If you would like to focus on making contributions about a particular building, street or area, please start by referring to the Survey’s Map of Areas Covered (see below). This map provides a guide to the geographical remit of each volume in the series. From here, a catalogue on our website contains links to online versions of volumes, available via British History Online or in the form of draft chapters uploaded to our website. The detail and scope of the volumes vary significantly, with a shift from the 1970s towards a more inclusive and contextual approach. Today the Survey aims to deal with buildings of all types and dates; with this in mind, it may be worth turning to the latest volumes if you would like to produce a fairly comprehensive map of a particular area. On the other hand, referring to earlier volumes will present an interesting challenge, with the opportunity to trace separately the recent history and evolution of a street or wider area.

Map of areas covered by the Survey of London (please click here to download a pdf version)

Alternatively, contributors to Colouring London could upload information from one of many gazetteers printed in Survey of London volumes. These lists contain concise descriptions and facts, such as key dates, architects and builders. Maps printed in the volumes will assist in comparing buildings listed in the gazetteer to building footprints on the Ordnance Survey’s MasterMap, which is the base for Colouring London. If you are not familiar with a particular street, it is worth visiting it in person or referring to online street views to check whether buildings still exist.

Gazetteers in recent volumes:

Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell (2008)

Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville (2008)

- King’s Cross Road and Penton Rise area

- Amwell Street and Myddelton Square area

- Percy Circus area

- The Angel and Islington High Street

- Pentonville Road

- Rosebery Avenue

Volume 48, Woolwich (2012)

Volume 50, Battersea (2013)

Volume 51, South-East Marylebone (2017)

- Marylebone High Street

- Cavendish Square

- Portland Place

- Queen Anne Street and Chandos Street

- Devonshire, Weymouth and New Cavendish Streets

Volume 52, South-East Marylebone (2017)

Populating Colouring London with age data from Survey volumes

If you are entering construction dates on Colouring London, please use the drop-down box to indicate the source and include a link to the online version of the relevant publication. This screenshot shows Farringdon Road, covered in the Survey’s Clerkenwell volumes (2008). For the purpose of simplicity, the database does not allow ranges to be entered. When the construction date for a building is listed as a range (such as 1882–3), please choose the earliest date (1882). If the façade date differs from the remainder of a building (for example, in cases of façade retention), please enter it in the box below.

We hope this guide will inspire our readers to contribute to Colouring London, and make use of the wealth of information collected and compiled by the Survey of London. This innovative website provides an exciting opportunity to collaborate with a broad network of people – from architects, historians and amenity groups to citizen scientists, local residents and students – to produce beautiful and meaningful maps of London.

Useful links

Survey of London volume on Oxford Street

By the Survey of London, on 3 April 2020

The Survey of London team is continuing with its work in isolation due to the current public health crisis. While it has been unfortunate but necessary to postpone two major events in our calendar, the launches of the Jewish East End Memory Map and a new volume on Oxford Street, these milestones can still be marked. Other projects in South-West Marylebone and Whitechapel continue to move forward.

Cover of Oxford Street, Volume 53 in the Survey of London’s main series. Published by the Paul Mellon Centre for the Bartlett School of Architecture at University College London (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

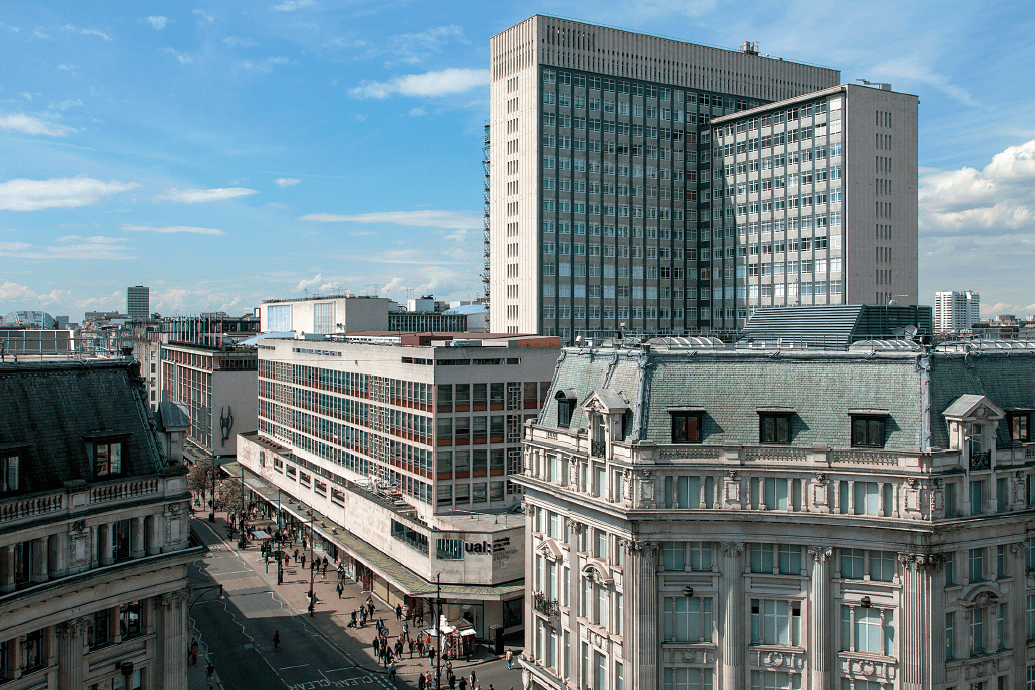

We are looking forward to the publication of Oxford Street, the fifty-third volume in the Survey of London’s main or parish series, on 14 April 2020. In the Survey’s 126-year history, Oxford Street is the first volume to focus on the development and architecture of a single street. In recent weeks images of Oxford Street have proliferated in the news, showing closed stores and pavements cleared of the vibrant street life and crowds that usually attract and repel visitors in equal measure – a reflection of these extraordinary times. The volume charts the history of the remarkable and enduring success of Oxford Street as a magnet for shoppers, examining its buildings and transport links as well as its social and cultural life.

Oxford Circus, buskers and Hare Krishna followers at entrance to the tube station, 2016 (© Lucy Millson-Watsons for the Survey of London)

The Survey’s new volume offers insights into the history and growth of shopping in London, along with the reasons for Oxford Street’s unique and enduring success – initially, its advantageous position between Mayfair and Marylebone, and later the fast and convenient transport networks that brought customers to its shops from the suburbs and beyond. Oxford Street is organized in a linear format, covering both sides of the street from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch. Twenty-two chapters cover discrete chunks of Oxford Street between the cross-streets, with an interest in existing buildings and those that have been demolished.

Looking west from Oxford Circus in 2016, with 242–276 Oxford Street and tower block at 33 Cavendish Square in centre, John Lewis beyond (© Lucy Millson-Watkins for the Survey of London)

The Survey’s research on Oxford Street followed on from the publication of two volumes on South-East Marylebone in 2017. That study covered an extensive portion of the West End north of Oxford Street, or the area bounded by Marylebone Road at the north, Cleveland Street and Tottenham Court Road at the east, and Marylebone High Street at the west. A fourth volume, South-West Marylebone, is currently in progress, examining the area immediately west as far as Edgware Road. This research on the West End is balanced by ongoing work towards two volumes on Whitechapel that are expected to be published in 2022.

As one of the longest continuous shopping streets in Europe, stretching for more than a mile in length, Oxford Street has a distinctive topography and character. It has been a major road since the Roman times, when it formed part of an arterial route leading westwards from the City. This highway came to be known as the Tyburn Road, a name derived from a brook (the Tyburn or Ay Brook) that has long since been overrun by urban development. By the time of the Norman Conquest, a hamlet had sprung up near the brook. In 1200 there was a small roadside church on the north side of the highway; its site may be identified today as somewhere between the two arms of Marylebone Lane.

Schematic map of Oxford Street and Edgware Road, c.1500–1700 (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

Tyburn as a place name was eventually replaced by Marylebone, after the dedication of the church following its relocation to a site further north in the fifteenth century. Tyburn carried dreadful associations of the public executions that were carried out on the site of the present junction at Marble Arch from 1196 to the 1780s. The highway served as the last route of condemned prisoners, who were often accompanied by riotous and drunken crowds of onlookers. By the seventeenth century the name Oxford Street was in common use, reflecting the highway’s status as the main route to Oxford. The emergence of the alternative name preceded the beginnings of bourgeois development on the estate of the Cavendish–Harleys from the 1710s, yet its use and adoption conveniently helped to shake off the notoriety associated with the gallows at Tyburn.

Today Oxford Street is better known as a popular centre for shopping, drawing in crowds of tourists and shoppers from the capital and its suburbs. Through the research towards the volume, it has been possible to pinpoint Oxford Street’s transition into a major shopping destination to the 1770s. By this time, the executions at Tyburn had ended and the road was resurfaced with granite blocks. The street lighting was also enhanced by increasing the number of lamps. Shopkeepers were attracted by the opportunity to establish shops on a major road within reach of the upmarket residents of Mayfair and Marylebone. Many entrepreneurs were connected with the drapery trade and set up in small shops based in single houses, often with staff accommodation on the upper floors.

Site plan showing properties purchased for John Nash’s circus of 1816–21 (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

Shopfront of Marks & Co., 395 (old numbering) Oxford Street, design by R. Norman Shaw, 1875 (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

In the nineteenth century the dominance of small shops was challenged by the rise of covered bazaars for small traders, often tucked into former yards or stable areas behind modest street fronts. The bazaar has often been understood as a precursor to the department store, which began to appear in Oxford Street with the rebuilding of Marshall & Snelgrove in the 1870s. Other major department stores of the late nineteenth century included John Lewis and D. H. Evans, which started as small drapery businesses before gradually engulfing entire blocks. These household names were joined by Bourne & Hollingsworth, Waring & Gillow and Selfridges in the Edwardian years. Department stores were furnished with comfortable amenities such as restaurants and rest rooms for customers, while staff were increasingly transferred from ‘over the shop’ accommodation to separate homes. Selfridges in particular represented a new scale of ambition, consumption and glamour among department stores in London and internationally.

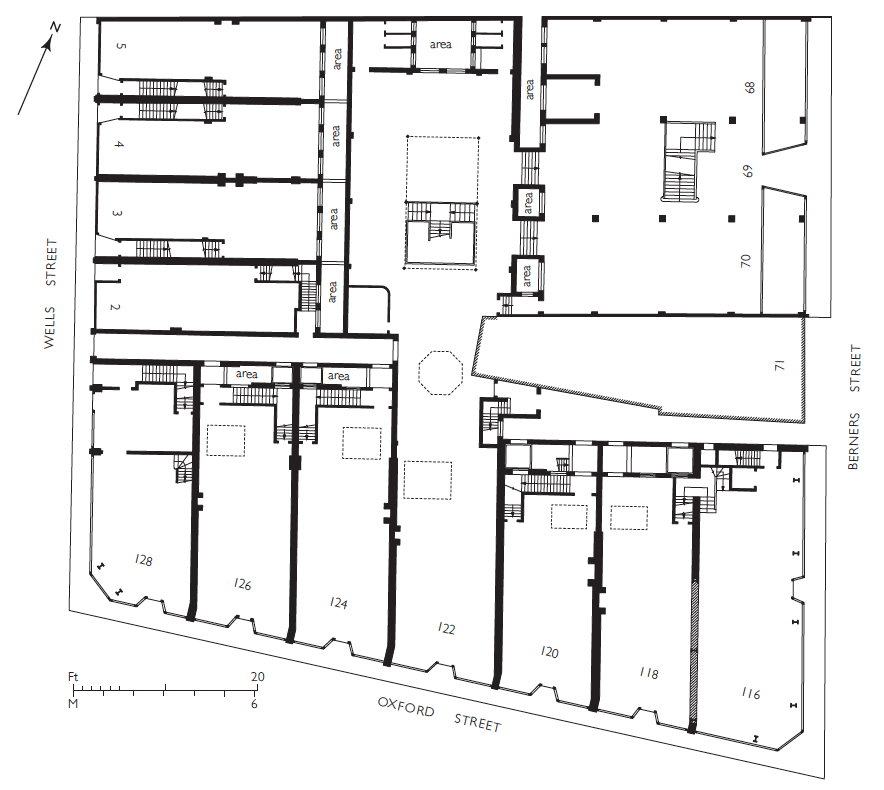

Plan of the ground floor of Bourne & Hollingsworth, c.1905. The store was then in possession of most of the block but had yet to unify the premises, which had been designed in 1898–1901 for separate occupation by smaller shops (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

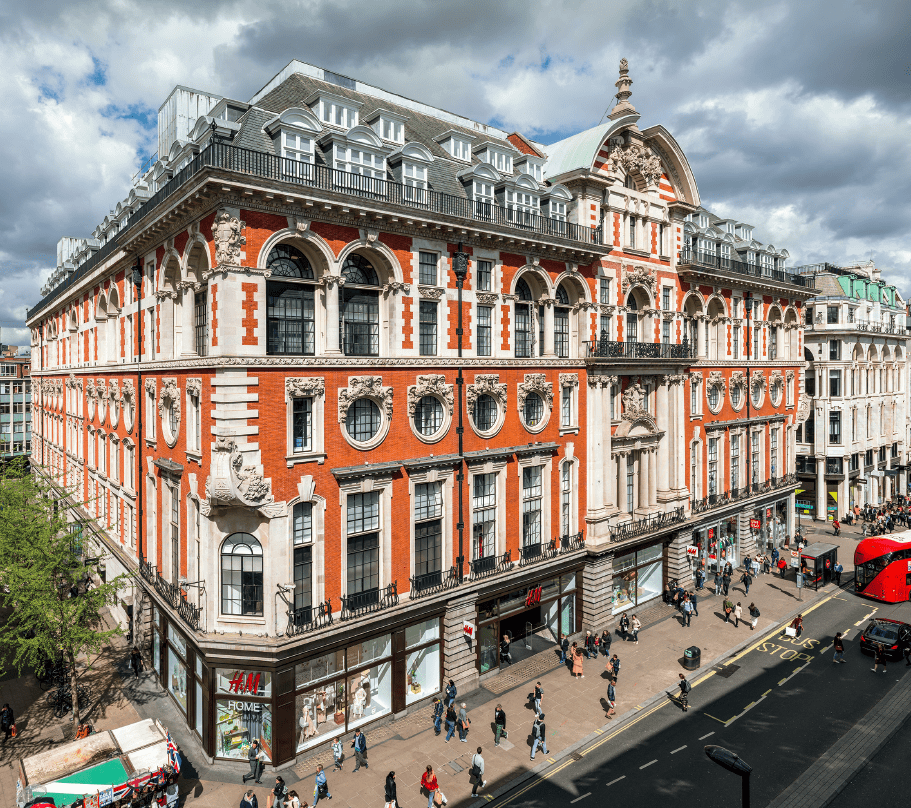

164–182 Oxford Street, former Waring & Gillow store, in 2019. R. Frank Atkinson, architect, 1904–6 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

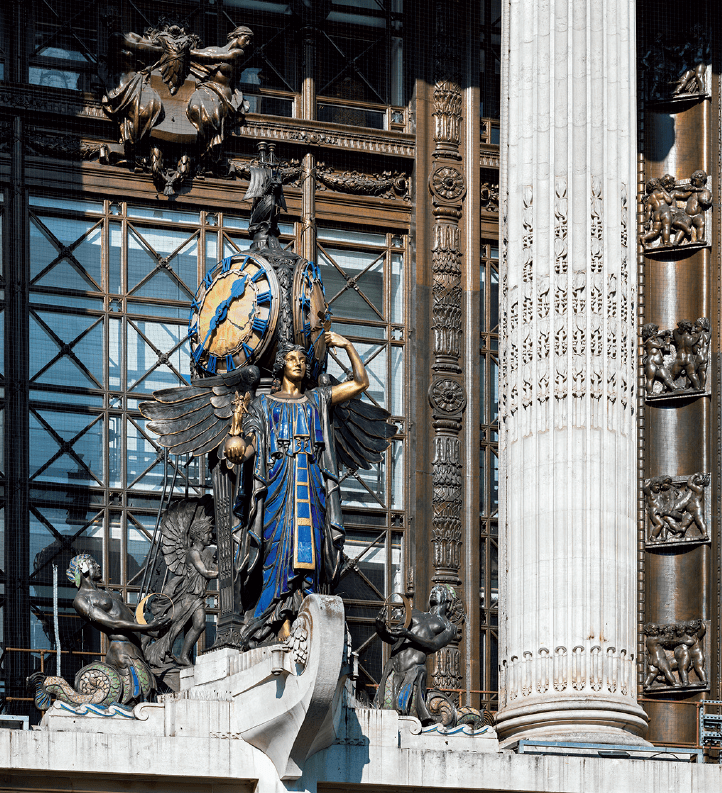

Queen of Time figure above the entrance of Selfridges in 2018. Gilbert Bayes, sculptor, 1931 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Peter Robinson, former restaurant on top floor of Oxford Circus block, now accounting department of Topshop, in 2013, with murals by George Murray (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The arrival of improved transport links in the Edwardian period extended Oxford Street’s appeal to shoppers, securing its status as the capital’s most continuously successful shopping street. Oxford Street was serviced by a range of underground lines connecting to four stations at Tottenham Court Road, Oxford Circus, Bond Street and Marble Arch. The Central Line was opened in 1900, followed by the Bakerloo Line in 1906. In the following year, the Northern Line opened at Tottenham Court Road. In 1969 the Victoria Line opened at the newly remodelled Oxford Circus Station, boasting a new concourse accessed from each quadrant of the circus. With the impending arrival of the Elizabeth Line, connections will be further improved.

Tottenham Court Road Station, vestibule with mosaics by Eduardo Paolozzi in 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Despite the concentration of shops and stores, Oxford Street has also long been a hub for entertainment, including restaurants, music halls, theatres and cinemas. The celebrated Pantheon, an entertainment venue first built to designs by James Wyatt in 1769–72, is the focus of a chapter that was written by the late Francis Sheppard and first published in Volume 32 on St James Westminster (1963). From the 1890s onwards tearooms and cafés sprung up at street level, led by the J. Lyons chain. Another well-known establishment was Frascati’s Restaurant, which operated in spacious and elaborate premises between 1892 and 1954. An early picture house was established at No. 165 in 1906, followed by Cinema House at No. 225 in 1910, when it was hailed by the Building News ‘the last word in living-picture theatres’. Social and cultural life continued to develop in Oxford Street during the Second World War, with bars, clubs and exhibitions along the street. The future 100 Club was established in 1942 as a venue for live jazz in the basement of 100 Oxford Street, where it continues today. Another remarkable survival is the Flying Horse, the last true pub in Oxford Street. The volume includes an appendix of Oxford Street pubs that conveys the extent of the pubs formerly in the street.

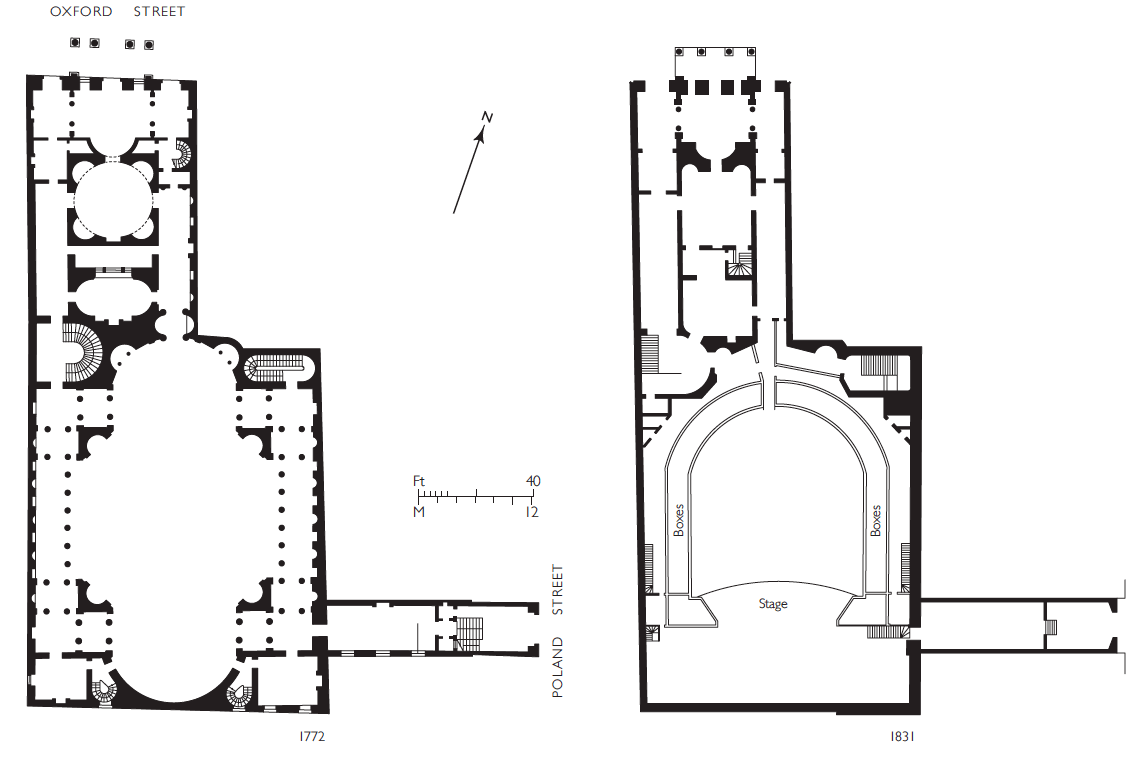

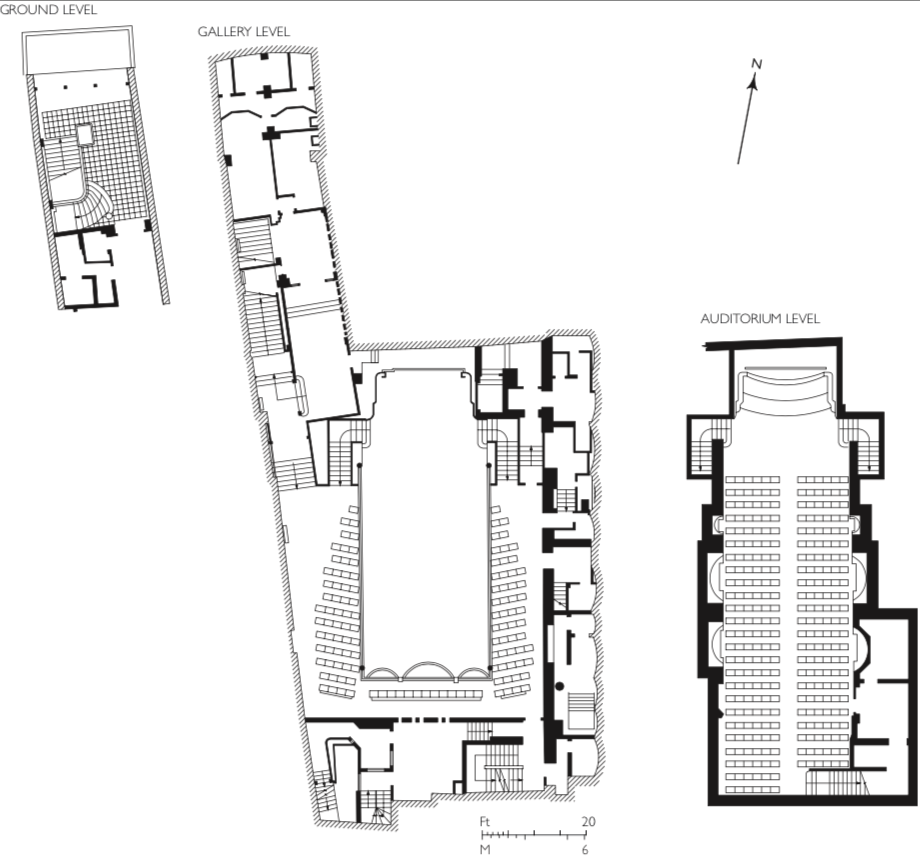

The Pantheon, plans. Left, ground plan as originally designed by James Wyatt, 1769–72. Right, ground plan in 1831 showing N. W. Cundy’s theatre of 1811–12 (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

311–317 (left to right) Oxford Street in 2016. Left, former Woolworth store at No. 311; centre, former Noah’s Ark pub at No. 313; right, part of Nos 315–319 (© Lucy Millson-Watkins for the Survey of London)

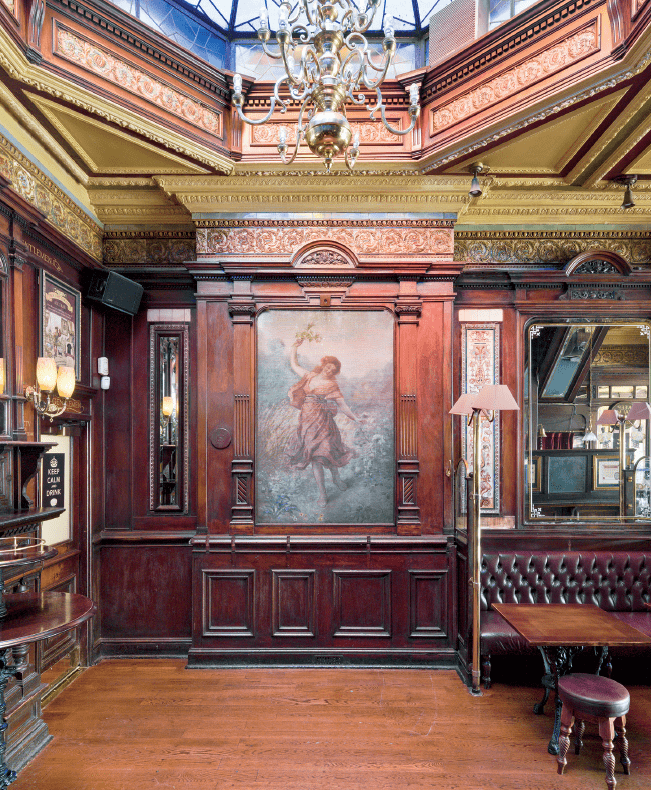

Flying Horse pub, interior detail, showing painting of Spring (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Pavilion Cinema, plan and elevation to Oxford Street, 1913. Frank Verity, architect (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

The 100 Club in the basement of 100 Oxford Street, 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Oxford Street contains more than 350 illustrations, including drawings and maps by Helen Jones, the Survey’s architectural illustrator, and a variety of historic photographs. New photography has been carried out by Chris Redgrave of Historic England with support from the Portman Estate. The volume also contains photographs of the sights and atmosphere of Oxford Street, recorded by Lucy Millson-Watkins in 2016. The volume has been edited by Andrew Saint and produced in the Survey’s current house style, designed by Catherine Bankhurst under the supervision of Emily Lees at the Paul Mellon Centre. The volume is now available from Yale Books for £75. The draft chapters have been made available online via our website, in advance of a fuller online version in the future.

Park House, 455–497 Oxford Street, looking east from Park Street in 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Memory Map of the Jewish East End

By the Survey of London, on 30 March 2020

We hope this finds our readership well. We intend to continue to publish posts on the Survey’s blog through these extraordinary times. We are still able to work from our respective isolations, and feel that short reads about aspects of London’s history are likely to be more than usually welcome diversions. An unfortunate consequence of our new circumstances is that, as has been the case everywhere, we have had to cancel events, including two launches, one of a website that was to have taken place at Sandys Row Synagogue on 29 March, another of a book, volume 53 in the Survey’s main series, about Oxford Street, that was to have happened at the London College of Fashion on 20 April. Our continuing posts will start with accounts of those two projects, the website first, then the book.

In collaboration with the artist and writer Rachel Lichtenstein, the Bartlett’s Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, the Space Syntax Laboratory and the Survey of London have together created a new website. It is a ‘Memory Map of the Jewish East End’.

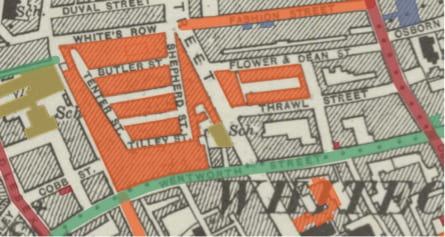

The Memory Map of the Jewish East End Historic Map CC-By-4.0. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

By 1900 the East End was home to over 100,000 Jewish people, most had recently arrived as refugees from Russia and eastern Europe. They settled predominantly in Whitechapel and Spitalfields, the heart of a thriving Jewish quarter, joining an already established community of Jewish migrants from Holland, Germany and other places. By the outbreak of the Second World War, the Jewish population in the area had already started to dwindle. Today very few tangible traces of Jewish East London are left —the kosher shops and restaurants, social and political establishments, synagogues and theatres have nearly all disappeared. The Jewish East End is on the verge of slipping from living memory.

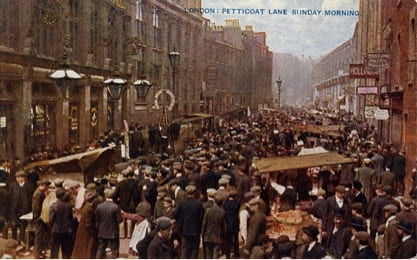

Postcard showing Petticoat Lane market in the early twentieth century

The new website is an interactive ‘Memory Map’ allowing visitors to explore the social and cultural history of the Jewish community in east London. Rachel Lichtenstein’s substantial archive of audio interviews with former and current Jewish residents of East London is brought together with new and archival photographs, material from the Survey of London’s recent work in Whitechapel and other original research, some previously unpublished. Covering more than seventy significant sites, the website aims to become a lasting document of the history and memory traces of the former Jewish East End and to bring the stories, memories, voices and images of this vanishing landscape to new audiences.

Dedicatory plaque on the King Edward VII Memorial Drinking Fountain on Whitechapel Road. Photographed in 2016 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Metal relief sign made for the Jewish Daily Post by Arthur Szyk in 1935 on 88 Whitechapel High Street. Photographed in 2016 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Bloom’s Restaurant, 90 Whitechapel High Street, 1977. Copyright Shloimy Alman

To begin exploring the map, visit https://jewisheastendmemorymap.org/.

A detail from the Memory Map – the Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor, 9 Brune Street, Spitalfields

The Gunmakers’ Company’s Proof House complex, 46–50 Commercial Road, Whitechapel

By the Survey of London, on 21 February 2020

An irregular group of buildings on the south side of Commercial Road near its west end is a unique survival. Here a City Livery Company continues to exercise an original regulatory function on a site it has occupied for nearly 350 years. The buildings are the Gunmakers’ Company’s proof master’s house, proof house and receiving house (alternatively shop, office or room), all largely of the 1820s, and, to the west, the Company’s former Livery Hall, built in 1871, possibly incorporating earlier fabric from an East India Company storehouse of 1808.

The Gunmakers’ Company’s Proof House complex, showing the former receiving house and Gunmakers’ Hall, 46–48 Commercial Road, view from the north-east. Photographed in 2018 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The Worshipful Company of Gunmakers was instituted by charter in 1637, nearly fifty years after a group of gunmakers drew up draft procedures for proving the safety of firearms. Opposition from other interested parties – the Blacksmiths and Armourers – delayed the creation and adoption of the Company until a Royal Commission of 1631 recommended its institution. It received its charter from Charles I, but the proving of guns did not start until the charter was enrolled in 1656. This enabled the Company to test all new hand guns, great and small, pistols and daggs (heavy pistols), produced in London and for ten miles around, or imported, to search for the same, and to ensure that gunmakers had served a seven-year apprenticeship and produced a proof piece to the satisfaction of the Company. The Company’s first proof house, for testing the security of gun barrels by subjecting them to firing loads a quarter to a third heavier than normal, was built in 1657 near Aldgate on land owned by John Silke, a gunmaker. An explosion that damaged Silke’s premises may have encouraged the Company to take a new site in 1663, probably in the Minories or East Smithfield, the centre of the London gunmaking industry.

In 1676 the Company moved to its current site. This appealed, no doubt, because it was then in an open field and had no neighbours to disturb or damage. The site formed part of a larger holding bounded north and east by Church Lane, west by Goodman’s Fields, and extending south as far as present-day Hooper Street. This property was held in 1691 by John Nicoll, probably a Holborn soapmaker who had a family connection with Whitechapel through the Darnelly family, and from 1692 to 1703 by John Skinner, an apothecary with property in Whitechapel High Street. Skinner’s profession may account for the land being denominated the Physick Garden, though the name Jackson’s Garden was also in use. Skinner sold the entire property freehold in 1703 to Benjamin Masters, a mariner, and part was leased to Jonathan Keeling, a gardener, in 1720.

The Gunmakers’ site was at the north-west corner of the Physick Garden. It was an irregular rectangle of ground, approximately 85ft wide by 58ft deep, bounded north by a ‘mudd wall’ and ‘a passage made by and through the mud wall’, west by a ditch and a ropewalk, east by ‘the hedge next to the dung road’,1 and south by another ditch separating it from the rest of Masters’ land. The proof house of 1676 was built by Michael Pratt, a carpenter, who held a lease on the ground.

That proof house had to be rebuilt in 1713, this done by one John Rogers on a new sixty-one-year lease from Masters. Thereafter the Gunmakers acquired the freehold of the site. A proof master’s house was present by 1733 when the master, Humphrey Pickfatt, was taxed for the proof house and a dwelling.

Ground plans of the Gunmakers’ Company’s Whitechapel complex in 1752 (top) and in 1920. Drawing by Helen Jones for the Survey of London

In 1752 a boundary dispute arose with Sir Samuel Gower, who had become the freeholder of land adjoining to the south and west. A plan accompanying the agreement that resolved this dispute reveals that the Gunmakers’ site did not extend eastwards quite to what had become Gower’s Walk, from which it was separated by a long 10ft-wide strip of land, occupied by a greengrocer’s shop with a small house behind. At this stage the Gunmakers’ premises included the proof house, roughly 20ft square, to the east adjoining the greengrocer’s, a privy at the south-east corner of the yard, the 35ft-wide (so double fronted) proof master’s house to the west (on the site of No. 46), the charging house (for charging weapons prior to proof), a shallow building about 20ft wide on Church Lane, with a smaller marking room (for stamping proofed weapons with the Gunmakers’ proof mark) on its east side abutting a narrow yard intruding into the greengrocer’s site on the Gower’s Walk corner.

Datestone on the back wall of the former receiving house. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Thus lay the Gunmakers shortly before a major rebuilding, prompted because the proof house was once again ‘ruinous’. It was reconstructed in 1757–8 ‘on a more beneficial and useful plan’,2 with the proof master’s house adjoining. A date-stone survives, reset on an inner wall of the receiving house (see above). In 1760 the charging house, marking house and counting house, also ‘ruinous’, were rebuilt on the same sites.3 Contention arose in 1781 when Joel Johnson and others complained that the proof house damaged their investment in houses they had built nearby on Gower’s Walk, but the Gunmakers reasonably pointed out that the proof house had been in that location for more than a hundred years, builders must have been aware of this before they chose to build nearby. Further additions and improvements were made, though Johnson refused to sell the easterly strip of land he then held.

Further development happened on the establishment’s west side in the early nineteenth century. The East India Company had been acquiring arms from London gunmakers since 1664. From 1709 to 1766 and again from 1778 it used the Gunmakers’ Company’s facilities to prove its arms. The East India Company built a storehouse and inspection room in 1807–8 on a westerly strip of the Gunmakers’ site, of which it took a ninety-nine-year lease in 1815. A door gave access to the Gunmakers’ yard through which barrels were transferred to the proof house. Beyond, the westernmost end of the Gunmakers’ holding was also developed, with two street-side houses with rear workshops, built in 1812 by John Williams, a bricklayer, on a fifty-seven-year lease. These properties were occupied over the next thirty years by a hairdresser, a bootmaker and a watchmaker, and were together gradually taken over by George Story (1805–1874), a scale-maker and the leaseholder from 1839.

By 1823 the proof house was again dilapidated, and the master’s house ‘likely to endanger the lives of the proof master and his family’.4 Hereafter the site was rearranged much as it is today. The freehold of the easterly strip of land between the proof house and Gower’s Walk was acquired from George Waller, more amenable to a sale than his father-in-law, Joel Johnson. The new proof house and proof master’s house were built in 1826–7 at the north-east corner of the enlarged site, with a single-storey and basement receiving or entrance building adjoining to the west. These buildings were designed by the Company’s surveyor, Robert Turner Cotton (1773–1850), perhaps with input from his son, Henry Charles Cotton (1804–73). John Hill was the bricklayer, and James Bridger of Aldgate the carpenter. Foundations for the proof house, dug and redug, were five bricks thick and more than 12ft deep.

The Gunmakers’ Company’s proof house, Gower’s Walk, view from the south-east in 2015. Photographed by the Survey of London

The proof house itself, up against Gower’s Walk behind the proof master’s house, is outwardly entirely utilitarian, a rectangular stock-brick building with segmental-headed windows at upper levels, of a height necessary to cope with the pressures and gases generated by proving. Most of the windows are blind, though some at least originally had iron louvres to dispel the smoke and pressure. The interior was essentially one space under a cast-iron framed roof, though subdivided in its lower half into two unequal open-topped proving chambers, one the main ‘proof hole’, containing a bed of sand where multiple barrels could be tested at once, the charges set off by a trail of gunpowder. In 1835 the upper part of the proof room was lined with cast-iron plates by Graham & Sons to protect the structure from damage from exploding gun barrels. The original cast-iron roof frame and these plates survived until 1994.

The central bay of the former Gunmakers’ Company’s receiving house of 1826–7. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The proof master’s house on the corner is of conventional three-storeyed design, also in stock brick, with a round-headed ground-floor window, gauged-brick arch heads and a stuccoed door architrave and cornice. The single-storey receiving house, possibly incorporating fabric from the marking house of 1760, originally had a copper-lined gunpowder magazine within its attic. Its three-bay façade, again stock brick but heavily stucco-framed, makes a stronger if entirely conventional classical statement. Four pilasters frame openings, including a central entrance with consoles to a segmental pediment. A rectangular panel atop the entablature announces: ‘THE PROOF HOUSE OF THE GUNMAKERS COMPANY OF THE CITY OF LONDON. ESTABLISHED BY CHARTER ANNO DOMINI 1637’.

By 1857 the East India Company building was unoccupied as small arms for India had come to be supplied by the War Office. The Company surrendered its lease in 1860 and, following a report by the local architect G. H. Simmonds, the building was converted in 1863 to be a committee room for the Gunmakers’ Company. This room seems to have been largely incorporated, rather than rebuilt, when the Gunmakers redeveloped the west side of their property in 1871, extinguishing Story’s lease. Gunmakers’ Hall went up to designs provided by John Jacobs, the builder, but possibly the work of Simmonds. It included the old committee room and a new court room to its west with a new two-storey stock-brick front range in a lumpen Italianate manner. Portland stone dressings, now painted, include an arch-headed central door surround and a pierced cornice balustrade. The impressive panelled court room, with a slightly canted south end, has a bracketed coved ceiling with a central lantern. A heavy court room table was grandly set off on the east wall by a huge trophy of arms, a starburst of more than 1,000 bayonets, military swords, hammers, ramrods etc. In 1893 a further room was created above the committee room, with a staircase inserted at the front of the east side of the entrance lobby, this to designs by W. J. Lambert.

The persistence of the Gunmakers on the increasingly urban site had been challenged since Joel Johnson took issue in 1781. In 1802 the Gunmakers successfully resisted the trustees of the new Commercial Road’s plan to acquire the site, though an Act of Parliament limited the hours of the day when guns could be proved. The Gunmakers succeeded in keeping the site from the Commercial Road trustees once again in 1824, and also saw off further limitation on the hours of proving. In 1882 the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway Company pressed to acquire the site for a vast warehouse that went up to the south, but the Gunmakers had only to relinquish a small strip with sheds. Even so, the south walls of the proof house and court room had to be heavily buttressed following excavations for the railway warehouse’s north yard and extensive vaults.

Gunmakers’ Company’s workshop on the west side of the inner courtyard, view from the north with the inner wall of the proof house visible through the window. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Piecemeal repairs and improvements were made from time to time, mostly reflecting changes in the requirements of proof. The shift from muzzle-loading to breech-loading guns and the consequent need for more complex proving accounted for additions in the yard, a small proof house for testing breech-loading guns in 1866, by when secondary proofing could be conducted with a gun fixed in a frame firing into a bed of sand, and other proving-chamber sheds thereafter. By 1920 low-level viewing shops and proofing rooms snaked around the southern boundary including behind the court room, and a loading shop opened off the receiving room. The Company endured lean years in the 1920s and was obliged to sell Gunmakers’ Hall in 1927, the trophy of arms transferred to the Birmingham Gun Barrel Proof House.

Gunmakers’ Company’s inspection bench in the workshop on the south side of the inner courtyard, with the inner wall of the receiving house visible through the window. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The buyers were Israel Eichenbaum (1874–1935), the owner of a wholesale drapery at 20 Commercial Road, and his son-in-law, Pinkus Segalov (1902–1959), and the building was let to the Order Achei Brith and Shield of Abraham Friendly Society. Jewish friendly societies were similar to other such societies, operating a subscription on which members could call in times of sickness. Mainstream societies sometimes excluded Jews, so specifically Jewish societies came into being from the 1790s. The Order Achei Brith (‘Brethren of the Covenant’), founded in 1894 out of a friendly society founded in 1888, was the first fully to embrace a Masonic character, operating as a Lodge with ceremonies, elaborate regalia and rituals. It merged with the Shield of Abraham Society in 1911 and, in common with other registered friendly societies, was empowered to administer the National Health Insurance Act of that year. It was one of the largest such societies by 1928 when alterations were made by Bovis Ltd to close up the connections between Gunmakers’ Hall and the courtyard of the proof house. The building, now called Absa House, was opened as the Order’s headquarters by Lord Rothschild on 14 October 1928, the consecration conducted by the Chief Rabbi. In 1933 the Order had around 25,000 members. What had been proofing rooms in the yard behind the court room were then rebuilt as an office, reached from a door formed from one of the court room windows. The new room was fully lined in modish vaguely art-deco wooden panelling.

The creation of the welfare state and the loss of the powers bestowed in 1911 reduced the practical need for friendly societies. Meanwhile the Order’s membership dispersed and failed to rejuvenate. By 1948 it was down to around 5,000 members. Amalgamation with the Order Achei Ameth in 1949 formed the United Jewish Friendly Society. From 1955 to 1958 what was now 46 Commercial Road was let to the St Louis Club, a social club, with alterations made by H. J. F. Urquhart, architect, for a restaurant in the former court room, a lounge in the former committee room, and a first-floor billiard room. Thereafter the basement was relet to the Gunmakers for arms storage, with alterations for access through the party wall overseen by Morris de Metz, architect. No. 46 reverted to being offices for the Friendly Society, part let off to Joseph Textiles Ltd, until 1976, shortly before the society’s dissolution in 1979.

To return to the east part of the site, in 1927 the imminent loss of Gunmakers’ Hall caused the Gunmakers’ Company to knock the first-floor rooms of the proof master’s house together to form a new court room, tie-rods being inserted; R. Hewett was the builder. Following war damage, the Company made further alterations in 1952 to designs by Albert Robert Fox, architect, with Wilton & Burgess, builders, to convert the receiving house basement into the court room, the proof master’s house altered back to form a first- and second-floor maisonette. In 1959 glazed timber-framed lean-tos for workshops and rifle storage were added on the south and east sides of the courtyard by Morris de Metz and James Jennings & Son Ltd, builders.

Detail of the inner or west wall of the proof house, showing stone tablets commemorating the rebuilding of 1826 and the refurbishment of 1995. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The only major modernisation of the proof house itself took place in 1993–5 when Thomas & Thomas, surveyors, and E. F. Whitlam, engineers, oversaw works by W. M. Glendinning Ltd, builders. Two floors and a reinforced-concrete ring beam and lateral (spreader) beams were inserted, with a light steel-truss roof replacing late-Georgian cast iron. The extra floors, reached by a new staircase at the north end of the building, allowed for four smaller proofing chambers on the ground floor, equipped with ‘snail-catchers’ to contain the fired bullets, depleting their energy in complex bending lengths of metal tubing, in place of the traditional sandbanks, with ammunition storage, loading rooms, a testing laboratory, gun-mounting room and instrument room on the first floor. The second floor was reserved for storage.

Proof House interior, showing a Lee Enfield rifle set up for proof firing. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The former hall at No. 46 was sold by the United Jewish Friendly Society in 1976 to the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), a private bank based in Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands, founded in 1972 and rapidly expanding to become the world’s seventh largest private bank. It closed in 1991 when it was revealed to be a giant money-laundering scheme. The former court room became a banking hall with desks and cashiers, the floor in the canted bay removed to create a double-height space, connecting to the basement by a spiral staircase, with a vast window filling most of the south wall. Six new openings were made on the north and east sides, connecting east to the former committee room, now subdivided into a manager’s office and corridor, and north to the lobby. The one-time first-floor billiard room became a conference room. The architect was Harry S. Fairhurst. After the winding up of BCCI, the Gunmakers’ Company offered the liquidators £80,000 for the building. This was rejected and the building sold at auction for £120,000 to Itzik and Adrienne Robin and Robert and Stephanie Itzcovitz. The Gunmakers finally reacquired the building for £1.1m in 2007. After the departure of BCCI No. 46 was used as a textile showroom until conversion to educational use in 2002, first as an outpost of the City of London College at 71 Whitechapel High Street, and since 2009 as the London College of Christian Revival Church Bible School, founded in South Africa in 1944.

Following the closure of branch proof houses in Manchester and Nottingham in 1996 and 2000, Gunmakers’ Company proofing of military weapons in Whitechapel has increased. By 2008 the proof master’s house was no longer residential, being reserved entirely for offices.

Proof House interior, proofing bay mechanisms. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Display of cartridges in the proving workshops. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

A hundred years ago, the Builder observed of the Gunmakers that ‘[t]he history of the Company is devoid of the romantic and historical associations connected with most of the misteries (sic), and is that of a well-organized and managed commercial undertaking, doing much useful work and deriving the necessary income from the fees charged for testing and proving weapons’.5 That still holds true.

References

1. London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), CLC/L/GI/G/001/MS05231

2. LMA, CLC/L/GI/G/001/MS05227/001

3. LMA, CLC/L/GI/G/001/MS05220/009

4. LMA, CLC/L/GI/G/001/MS05227/001

5. The Builder, 8 October 1920, pp. 400–1

London buildings photographed by the Survey of London’s students

By the Survey of London, on 24 January 2020

Since 2015 the Survey of London has been responsible for teaching a module in the Bartlett School of Architecture’s Master’s degree course titled Architecture and Historic Urban Environments. Our module, ‘Surveying and Recording of Cities’, includes instruction in architectural photography, led by Chris Redgrave of Historic England, with whom we have been delighted to work in recent years. Students may submit photographs as an aspect of their coursework.

Alexandra Road Estate (photographed by Iason Ntounis)

Old St Pancras Church (photographed by Tyesha McGann)

Frobisher Crescent at the Barbican (photographed by Yumeng Long)

Church of St Andrew Undershaft (photographed by Zhan Shi)

The British Library (photographed by Steve Ge)

St Christopher’s Place

By the Survey of London, on 25 December 2019

Tucked away up a narrow alley off Oxford Street’s north side, St Christopher’s Place has been a characterful shopping destination for many years. Almost all the buildings are Victorian or later, but the street dates back to the 1760s. When it was first built up most of the surrounding area belonged, as much of it still does, to just a couple of landholdings – the Portman estate and what is now the Howard de Walden estate. There were a few smaller holdings too, one of which was Great Conduit Field, named from the City of London Corporation’s medieval water supply system which ran through Marylebone Fields and on to Cheapside. Great Conduit Field fronted Tyburn Road, as Oxford Street was then known, and extended west from the Ay Brook – part of the river Tyburn, now covered by the buildings on the west side of Stratford Place – to halfway between Duke Street and Orchard Street. Selfridges covers the line of the old field boundary. In the mid eighteenth century this ground came into the hands of Thomas Barratt of Brentford, one of a number of prosperous brick and tile makers digging and baking clay all along Tyburn Road and beyond for the London building trade. In 1760 his only child Ann married Thomas Edwards of Soho, heir to a Shropshire baronet. Barratt died a couple of years later. By this time much of the wider area was being laid out in streets and built up, and in 1765 two partners – Richard Forster, a bricklayer, and John Crowther, a plasterer – agreed to build houses on Great Conduit Field in return for long leases.

St Christopher’s Place as Barrett’s Court, running north from Henrietta Street, c.1870 (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland)

Part of the new development was Barratt’s or Barrett’s Court, the narrow street now called St Christopher’s Place. The wider Barrett Street at its south end was originally (and until 1879) called Henrietta Street, and as the name implies was intended to have gone on eastwards, to join up with present-day Henrietta Place near Cavendish Square. But the creation in the 1770s of Stratford Place, a gated enclave on land belonging to the City Corporation, put paid to the plan. That may have had a lowering effect on the value of Great Conduit Field generally, which became a mixed area of trades and crafts with some notably poor and over-crowded patches.

Barrett’s Court can never have been other than a fairly lowly address. Even so, it is interesting that it was called a court, as the often down-market term was mostly applied to blind alleys or yards with only pedestrian access, not proper streets. The reason is that when Barrett’s Court was first laid out the west end of Wigmore Street did not exist, sothe north end, near the field edge, would have been closed. That changed a little later, when Wigmore Street was extended west to Portman Square. Not that it was actually acknowledged as such – amour-propre on the part of the landowners meant that one end of the extension took the name Edwards Street, and the Portman-owned remainder became Lower Seymour Street. A pub was built there on the corner of Barrett’s Court, the Pontefract Castle, opened in 1771 and closed only in recent years.

Corner of Barrett Street and James Street leading to St Christopher’s Place, December 2019 (Photographed by Ecem Ergin, PhD student at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL)

Barrett’s Court became part of the long-standing Irish colony in this part of Marylebone, packed with inhabitants most of whom worked outside the district. In 1838 one of the dilapidated houses collapsed, though with enough warning for the occupants to escape. An old woman who refused to leave was rescued from beneath the rubble. Like the even narrower Gee’s Court connecting it with Oxford Street (named after its builder in the early 1770s, John Gee), Barrett’s Court was typical of the slum courts found throughout central London, in which unchecked sub-letting of rooms and a fundamental inadequacy of fresh air and daylight militated against almost any conceivable sanitary improvement. An instance of the prevailing conditions in the area is given by the report of an inquest in 1857 (held at the Lamb and Flag on the Barrett Street–James Street corner) into the death from respiratory disease of a labourer’s child at the truncated end of Barrett Street, characterized as a ‘low, dirty by-street’. There were said to be 30 to 40 people in the house altogether, and the household in question comprised a widower and sister-in-law with their respective several children living in the basement. There was no ventilation other than the area doorway and, in the coroner’s words, ‘not sufficient air for a mushroom to grow’.1

In the late 1850s the parish Vestry did manage to bring about some improvements, and the condition of Barrett’s Court was mentioned in proof of this by the local Medical Officer of Health in 1858. But it remained a poor address, and when Mandeville Place was planned in the early 1870s hope was expressed that it would be taken all the way to Oxford Street, with associated slum clearance sweeping away ‘those fever dens, Barrett’s court and Gee’s court’.2 Instead, both courts were subsequently improved and rebuilt, preserving their back-alley dimensions for posterity.

The north end of St Christopher’s Place, looking towards 78–80 Wigmore Street. An outlet of the Danish bakery chain Ole & Steen occupies the former Pontefract Castle public house at 71 Wigmore Street (Photographed by Ecem Ergin)

A further attempt at improving the locale was the parish’s erection of a surface street urinal in Barrett Street in 1865. Tradesmen in the neighbouring streets, including the landlord of the Lamb and Flag, soon wanted it removed. Put euphemistically, ‘it was made a water-closet, a brothel, and was such a great nuisance that the lodgers were leaving the different houses adjacent’.3 But it was decided that the benefits outweighed the drawbacks. In 1910 it was replaced on the same site by the surviving underground convenience.

The housing reformer Octavia Hill’s involvement at Barrett’s Court began in 1869–70, with the purchase of eleven leasehold houses by her associates Julia, Countess of Ducie, and Emma Brooke, wife of the popular preacher and writer Stopford Brooke. Lady Ducie offered practical assistance as well as money – Emma Brooke was an invalid and could not do so – but at least early on the management of Barrett’s Court was largely in the hands of Hill’s disciple Emma Cons, who later founded the Old Vic. More houses were acquired, until Hill and her helpers were in effective control of most if not all of them. Her approach being essentially personal, moral and exemplary, there was no thought at first that the houses should be rebuilt along model-dwellings lines, and as they were leasehold that would not necessarily have been possible anyway. When some of the houses were declared unfit by the Medical Officer and had to be rebuilt, she was ‘obviously annoyed’.4 Rebuilding, however, allowed for more and better dwellings as well as lucrative shop units.

23 Barrett Street (Photographed by Ecem Ergin)

‘Blank Court; or, Landlords and Tenants’, her account of Barrett’s Court, was first published in 1871 and was at once denounced by the Medical Officer, Dr Whitmore, as ‘a clever fiction, rather than a narrative of actual facts.’5 He thought she was sensationalizing the subject and exaggerating both the bad condition of Barrett’s Court in 1869 and the extent to which her management had improved it. She replied with a detailed list of what had done by way of repair and improvements in drainage, cleaning and management, and the two met. Somewhat mollified, Whitmore declared himself ‘strongly impressed with the earnestness of her purpose’.6 But there was a further clash with the Medical Officer and Vestry in 1874.

Rebuilding took place in three stages, beginning with houses on the east side, replaced by Sarsden Buildings in 1873, and continuing in 1877 on the west with several more, rebuilt as St Christopher’s Buildings, subsequently designated North St Christopher’s Buildings. The final block, South St Christopher’s Buildings, followed in 1881–2.

The area in the 1890s (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland)

Sarsden Buildings was financed by Lady Ducie (1829–1895), whose London residence was in Portman Square, and named after her birthplace in Oxfordshire. Its building followed her acquisition of the freeholds of the houses on the site when these were put up for sale with other properties on the now fragmented Great Conduit Field estate in 1873. In their original form the individual tenements were very basic, consisting of small two-room ‘sets’ accessed from open balconies at the rear. This remained the arrangement until the block was modernized in the 1960s to make proper flats, each with its own compact bathroom and kitchen. By then the upper floors of No. 1, the sole survivor of the original houses in the street, had been added to the ensemble.

In the basement, entertainments were organized by Emma Cons and the author George MacDonald, who wrote plays to be performed there. A visitor in the 1880s found it ‘the most cheerful by far of the many club rooms for the poor that I have seen’, but gives an impression of some awkwardness: ‘On the little round tables I noticed all sorts of illustrated papers – the Graphic, and Illustrated News, and even Punch. There was excellent tea and coffee at a penny a cup, and a kind of concert was given by some good-natured amateurs. The people seemed to enjoy themselves a good deal, in a quiet sort of way. The women brought their babies – wretched-looking little mites most of them … Miss Hill and some of her lady-helpers moved about amongst the people, and seemed to know them all by name’.7

Sarsden Buildings on the east side of St Christopher’s Place (Photographed by Ecem Ergin)

St Christopher’s Buildings were built on long leases from the freeholder H. J. Hope-Edwardes, a descendant of (Sir) Thomas Edwards. Although Emma Brooke had bought the old houses, she died young in 1874 and the rebuilding was seen through by her brother, the banker and Liberal politician Somerset Beaumont. Another very plain structure, the north block originally comprised tenements of one, two and three rooms, with shops and a basement laundry. The southern block at least was designed by Octavia Hill’s favoured architect Elijah Hoole, who gave it a red-brick Gothic front with distinctive curved doorways on the street. The name of the development was suggested by Octavia herself: ‘The world would fancy it was named after some old church; and I should hear the grand old legend in the name. Is it too fantastic a name?’8 In 1884 the street became St Christopher’s Place.

Though the Victorian rebuildings have survived, some of the old tenements are now luxury apartments. But the tradition of social housing here continued with the construction in 1964–5 of the modern-style flats, over shops, at 6–8 St Christopher’s Place, designed for the St Marylebone Housing Association Ltd by Green & Monk, architects, of Forest Gate.

14–15 St Christopher’s Place (Photographed by Ecem Ergin)

Following the improvements in housing brought about by Octavia Hill and her followers, in the early twentieth century there was another notable female enterprise, at the corner of St Christopher’s Place and Barrett Street. Much rebuilding was going on around this time, including the redevelopment at 3–5 Barrett Street, undertaken speculatively by Charles Pedlar, an engineer and gas-fitter of Bird Street, who developed several sites in the area. No. 5 became his own new premises, while the greater part of the block was first occupied by the newly incorporated Women’s Dining Rooms, Ltd, whose restaurant exclusively for women opened there in 1904. Its founders included May Tennant, the first woman factory inspector, her husband the Liberal politician H. J. (Jack) Tennant, and Thereza Rücker, wife of the physicist and principal of the University of London, Sir Charles Rücker. Young shop assistants and typists were the typical intended clientele. The shareholders, most of them women, were drawn mainly if not exclusively from the upper classes. Larger subscribers included the Wigmore Street store owner Ernest Debenham; the promoter of model dwellings and the Rowton Houses, Sir Richard Farrant; the future peace campaigner Lord Robert Cecil; and the barrister Henry Bonham Carter. May Manning of the Ladies’ Empire Club in Mayfair became manager.

Christmas decorations at St Christopher’s Place (Photographed by Ecem Ergin)

It was acknowledged that good midday meals were unaffordable for most working women, and that charity restaurants would only encourage the acceptance of less than living wages. The need for such meals had been ‘felt and successfully met in many foreign towns’ and it was hoped the same could be done in London.9 The kitchen was at the top, and dinners, to a basic menu of meat, fish, vegetables, soup, bread and cake with tea or coffee, were served below from midday in two rooms seating nearly 300 in all. They cost only a few pence, but there were flowers and white tablecloths, and lavatories and a rest-room with newspapers and magazines, available without extra charge. Although similar to the Dorothy Restaurants begun in Mortimer Street, Bond Street and Oxford Street in the late 1880s, the venture was hailed as a novelty. A conference and entertainment, overseen by the National Union of Dressmakers’ and Milliners’ Assistants, was held there in 1906, and the restaurant may have been set to become a centre of the women’s movement. But it did not pay and in 1909 had to close.

The premises were subsequently occupied by the London Home Delicacies Association Ltd, run by Harriet Converse Moody of Chicago, who held the Earl’s Court Exhibition catering contract. She was the wife of the American poet and playwright William Vaughan Moody, and the friend of literary figures including Robert Frost and Rabindranath Tagore. As a professional caterer, she had contracts with the Marshall Field store and Chicago railways. The business was not a success, however, and from the First World War or soon after the building was used as garment workshops. The Antique Supermarket was started there in the 1960s, an establishment which helped put St Christopher’s Place on the map for trendy shoppers.

The Lamb and Flag public house at the corner of Barrett Street and James Street (Photographed by Ecem Ergin)

The secondhand furniture trade was well established in Barrett’s Court by the mid nineteenth century. It survived the street’s extensive redevelopment, and in the early twentieth century there were also businesses in related fields such as cabinet making, art metalwork and gilding. By the 1930s St Christopher’s Place was known for its rather picturesque concentration of antique shops. The writer E. V. Lucas found it comparable in atmosphere to Cecil Court off Charing Cross Road, but instead of the antiquarian prints and books found there it specialized in furniture and bulky objets, with ‘life-size statues, carved overmantels, bureaux, often encroaching on the pavement’.10 An old-fashioned ambience survived the Second World War but by the early 1960s the picture was beginning to change. A modern furnishings showroom was opened at No. 10 by the Custom Design Group, which had been set up by a consortium of companies ‘to raise the standard of British design’.11 This sold relatively upmarket product ranges for the home including commissions from well-known names such as Lucienne Day. Bennie Gray’s Antique Supermarket, opened in 1964, tapped into the nostalgic, often off-beat, taste for Victoriana and Art Nouveau which was swiftly developing alongside that for ‘Contemporary’ design. The basic idea, of independent stalls operating under one roof in the manner of a bazaar was not a new one to London, and a successful precedent in the antiques trade had been set as early as 1951 by the Red Lion Antiques Arcade in Portobello Road. Gray followed the original supermarket with a series of antique centres – the Antique Hypermarket in Kensington, Gray’s in Mayfair, Alfie’s in Church Street off Edgware Road, and Antiquarius in King’s Road.

The Lamb and Flag (Photographed by Ecem Ergin)

Planning permission for redevelopment on the west side of St Christopher’s Place had been granted when in 1967 the property was bought by the developer Robin Spiro, in conjunction with Allied Land. Spiro was taken by the street’s character and instead of redeveloping set about renovating the buildings, employing the Irish designer William Graham, and re-letting the shops. Graham was also commissioned to fit up one of the shops as the Redmark Gallery, which opened in 1968 and was associated with contemporary and avant-garde artists including the experimental film-maker Stephen Dwoskin.

With this new approach, St Christopher’s Place and streets in the immediate vicinity became a shopping destination in their own right, a much-needed counterweight to the hectic, hard-sell atmosphere of main-street retailing and fast-food catering typified by Oxford Street. St Christopher’s Place became well-known for unusual shops selling such items as jewellery and crafts products. Hiroko, the ‘first fully authentic’12 Japanese restaurant in London, opened there in 1967 and was followed by Kazuko on the corner of James Street. In 1968 the still-extant Amjadia Indian restaurant opened in Picton Place near by. The neighbourhood is now home to restaurants of many ethnicities, and the east end of Barrett Street is an oasis of eateries with outside seating.

1 Barrett Street (Photographed by Ecem Ergin)

In the 1970s, working with the Imperial Tobacco Company Pension Fund, which owned property locally, Spiro planned a retail ‘village’ named Craftown, partly modelled on San Francisco’s Ghiradelli Square. The idea was to turn the block north of Barrett Street, between St Christopher’s Place and James Street, into a glass-roofed precinct, with shops and restaurants specializing in national or ethnic, particularly third-world, crafts and cuisine, together with exhibitions and other promotional activities. Agreements for participation were made with numerous countries including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, Greece and Iran.

The full vision of Craftown remained on paper, but St Christopher’s Place was successfully improved and regenerated during the 1970s and 1980s. On the west side, the old tenements were refitted as luxury apartments and offices, while the street was repaved and buildings refurbished as craft and other specialist shops, galleries, restaurants or wine bars. By the early 1980s it was becoming established as a centre for high-class fashion and fashion accessories. Well out of the retail mainstream was Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s Nostalgia of Mud at No. 5, in 1982–3, conceived to display an earth-coloured clothing collection of the same name based on Peruvian ethnic dress, and as much art installation as shop. The shopfront was obscured by an exterior hanging in the form of a world map fashioned in relief in plaster, and the interior incorporated a brown ceiling drape, a pit of ‘mud’ bubbling under a grating, and scaffolding apparently to suggest to the unadventurous that building was still in progress and the shop not yet open.

View looking south along St Christopher’s Place (Photographed by Ecem Ergin)

References

- Morning Chronicle, 4 Sept 1857

- Marylebone Mercury, 14 Jan 1871

- Marylebone Mercury, 22 July 1865

- Robert Whelan, Octavia Hill and the Social Housing Debate. Essays and Letters by Octavia Hill, 1998, p. 66

- Marylebone Mercury, 18 Nov 1871

- Marylebone Mercury, 18 Nov 1871

- Norfolk News, 12 Jan 1884

- C. E. Maurice, ed., Life of Octavia Hill: As Told in Her Letters, 1913, p. 351

- The National Archives, BT31/10556/79790

- Sunday Times, 26 Sept 1937

- Sunday Times, 7 Jan 1962

- The Guardian, 8 Dec 1967

Oxford Street

By the Survey of London, on 29 November 2019

The Survey of London looks forward to the publication of the 53th volume in its main series in April 2020. Oxford Street is among the world’s great shopping streets, renowned for its department stores and the vitality of its crowded pavements. After well over 200 years of retailing, it stands unchallenged as London’s most continuously successful magnet for shoppers. As a thoroughfare Oxford Street is far older, going back to Roman times. Under its earlier name of Tyburn Road, it was notorious for centuries as the route of the condemned to the gallows on the site of the present Marble Arch. The volume will be the first in the Survey of London series to deal with the development and architecture of a single street. No major London street has ever received such a complete analysis, offering fresh insights on the growth of shops and shopping in the British capital and illuminating the variety of buildings and activities that have given Oxford Street its striking and fluctuating character. It also explains the reasons underlying Oxford Street’s unique success – at first, its position between opulent Mayfair and Marylebone, later, the array of underground lines affording fast and easy access to its shops.

Following the success of making draft texts of Woolwich, Battersea and South-East Marylebone available online, the Oxford Street texts have now been released on the Survey of London’s website. The draft chapters may be viewed or downloaded as pdf files. The chapters include references but not illustrations. The print volume will follow next April, published by Yale University Press on behalf of the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. The Survey of London’s website contains a catalogue with links to online versions of volumes in the main series and monograph series. For some time, volumes 1 to 47 of the Survey of London have been available via British History Online. Print copies of the most recent volumes, including Oxford Street (which may now be pre-ordered), are available from Yale Books and other booksellers.