What will the Euro elections tell us about Eastern Europe?

By Sean L Hanley, on 11 May 2014

Seán Hanley looks ahead to the upcoming European elections and assesses what they may tell us about the enduring differences between voters and parties in Western and Eastern Europe.

The elections to the European Parliament which take place across the EU’s 28 member states between 22 and 25 May are widely seen a series of national contests, which voters use to vent their frustration and give incumbent and established parties a good kicking. Newspaper leader writers and think-tankers got this story and have been working overtime to tell us about a rising tide of populism driven by a range of non-standard protest parties.

The conventional wisdom is that the ‘populist threat’ is all eurosceptic (and usually of a right-wing persuasion) although in some cases the ‘eurosceptic surge’ is clearly a matter of whipping together familiar narrative than careful analysis.

But, as a simultaneous EU-wide poll using similar (PR-based) electoral systems, the EP elections also provide a rough and ready yardstick of Europe-wide political trends, ably tracked by the LSE-based Pollwatch 2014 and others.

And, for those interested in comparison and convergence of the two halves of a once divided continent, they a window into the political differences and similarities between the ‘old’ pre-2004 of Western and Southern Europe and the newer members from Central and Eastern Europe (now including Croatia which joined in 2013).

Socialists and EPP

Pollwatch 2014 projections for May suggests that Social Democrats (the Socialists & Democrats group in the EP) will as in 2009 set to be the only EP group to have representatives from every EU member states. Interestingly – and notwithstanding the obvious differences of context between historic socialist and labour parties of Western Europe and the (usually) reformed ex-communists of the East – social democratic parties seem set as in 2009 to perform (and to gain) at very similar levels in both the old and new EU.

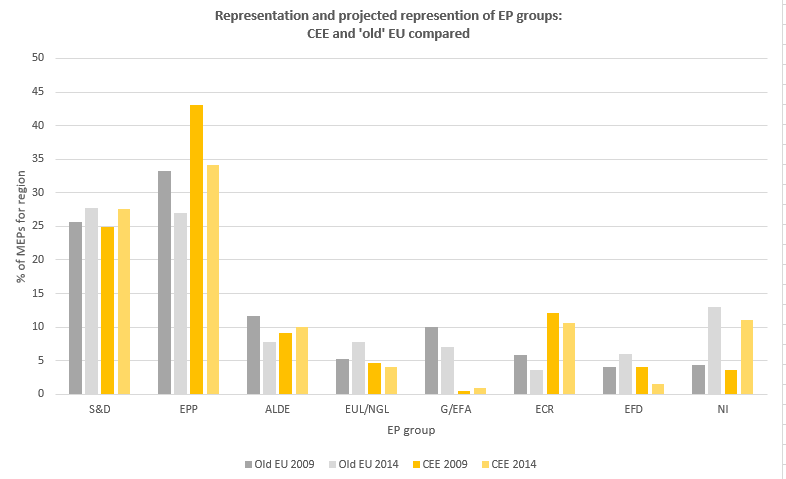

This is not quite so with the other big grouping with truly EU-wide representation, the European People’s Party. Although Christian Democratic parties barely exist in CEE – and where they do tend to be niche groupings – in 2009 the EPP (or at least centre-right parties that joined the EPP group) won heavily in the new member states taking a whopping 43% of the region’s representation: 85 of the 197 MEPs from CEE in the outgoing European Parliament sat with the EPP, compared to just over a third for old member states (and 36% in the Parliament as a whole).

Pollwatch suggests that the EPP will take a hit in the May’s elections, losing around a fifth of its representatives and falling to around 29% of the seats in the new Parliament. Interestingly, the projections, suggest that these loss will be of similar scale in Central and Eastern Europe and pre-2004 member states, leaving the EPP better represented in CEE.

The obvious explanation would be that the EPP hoovers up ragbag of centre-right parties from Poland’s liberal Civic Platform to Hungary’s distinctly illiberal Fidesz and the absence of distinct non-Christian Democratic conservative right in the East.

But a quick look at the anti-federalist European Conservatives and Reformers (ECR) group, the closest approximation to a bloc of mainstream conservative non-Christian Democrats, shows that it is (and if re-formed would remain) the most Central and East European dominated in the EP. Even with the Czech Civic Democrats likely to be cut down to a single MEP (from 9), if it survives more than half the ECR’s members will come from CEE – largely as a consequence of the British Tories’ big losses at the hands of UKIP and the relatively strong performance of Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland.

The ECR may gain one recruit from Slovakia in the person of Jozef Viskupič of the mercurial outsiders of the Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OĽaNO). OĽaNO however sensibly qualify their sympathy for the ECR by telling their Facebook friends (8 April) it ‘depends whether the voters redraw the political map so much that more meaningful group arise than at present’.

Radical left weak, Greens weaker

Pollwatch’s research also confirms the continuing weakness of the radical left in the new CEE member states. The Nordic Green Left – United European Left group is predicted to see its numbers grow modestly– from 35 (4.8%) to 41 MEPs (6.8%). This pattern will be repeated in CEE from a low base: a jump from 5 to 8 MEPs, or just over 4% of the total for the region. Moreover, these come on the whole from two distinct and atypical groupings: the Czech Communists (KSČM) and Latvia’s Harmony Centre, a curious hybrid of Russian minority party and dullish responsible socialist party. Only the rise of Croatian Labourists, set to build on their success in the previous (2013) Euro-elections in the EU’s newest member state, would seem to compare with radical left inroads of the kind seen in the old member states. There is, to paraphrase Luke March, not much left of the radical left in Central and Eastern Europe.

The picture is rather worse, however, for the Greens: the Greens/European Free Alliance G/EFA) is, Pollwatch estimates, are set to slip badly in terms of overall representation the falling from 57 seats (7.4%) to 41 (4.5%). But both 2009 and projected 2014 result starkly emphasise that electorally successful Green parties are an almost entirely West European phenomenon: in the outgoing Parliament the G/EFA had a solitary, single member from the CEE member states: Indrek Tarand of Estonia, who was not even a Green but a radical independent (the official Estonian Green Party polled 2.9% in 2009).

Compared with 2009 CEE Greens seem set for a ‘mini boom’: they will double their EP representation with predicted one seat each in Hungary and Croatia and this time from genuinely Greenish parties: the Croatian Sustainable Development party (ORAH [= ‘walnut’]) of former environment minister (and ex-Social Democrat and noted social liberal) Mirela Holy and Hungary’s Politics Can Be Different (LMP) which despite a fractious existence as part of Hungary’s ineffective and divided left-liberal opposition seems, as in the April 2014 parliamentary election, set to squeak 5%. The bottom line is, while Green parties and activism exist (often quite vigorously) on the margins of CEE two decades after the fall of communism they still below (and usually way below) the 5-10% effective threshold needed to make in any numbers it even into the EP – even allowing for the smaller size of CEE states (median size of national delegation: 13 MEPs) compared to other EU states (21).

The liberal ALDE group will, Pollwatch predicts, also slip back badly coming in with a predicted 63 MEPS or 8.4% in the new EP as opposed to 10.3% in the old – although it may get a boost if the Czech ANO party of billionaire Andrej Babiš joins. Despite the divided and estranged relationships of members of the liberal party family, ALDE has rather the same catch-all appeal as the EPP for the CEE parties and (if we assume ANO does get on board) is predicted to have representatives from all the CEE member states bar Latvia and Hungary – suggesting slight gains in CEE, which could partly compensate for losses elsewhere. As with the EPP and ECR (if it endures), East and Central Europeans are predicted to be more heavily represented in ALDE relative to their overall EP representation. However, as the controversy over the recruitment of the much reviled media magnate and informal political powerbroker Delyan Peevski to the number two spot in the EP list of Bulgarian’s Turkish minority DPS party highlights- the CEE members of ALDE are something of a motley crew.

Finally, there are the non-inscrits: parties which have not – or do not appear likely to join any of the existing EP groups. Pollwatch’s projections suggest that the numbers of non-inscrits is likely to triple to around 12-13 percent of MEP, although this figures has to discounted given that many of the new, non-aligned parties will join existing group or form new groups. There, as Cas Mudde notes, is already intense manoeuvring to organise the far-right and more moderate but unorthodox right-wing eurosceptic parties in the new Parliament.

The rise of the non-inscrits according on Pollwatch’s projection, will be of very scale in both new CEE member states and the older EU. And, as in Western Europe, the non-inscrits will be a patchwork of old and new anti-establishment and outsider parties, some of the far-right, some not. Hungary’s very radical extreme right party Jobbik is projected to come in with alarming 22% which could see it radical edge into second place ahead of the mainstream left-liberal ‘Together’ alliance.

However, elsewhere the CEE far-right will enjoy only a modest uptick in already modest fortunes: the Slovene National Party (SNS), which dropped out of Slovenia’s parliament in 2011, seem sets to poll 10.4 per cent and win one MEP; Slovak National Party which exited its own national parliament in 2012 is forecast to pick up 6.7% (also one MEP); the new Alliance for Croatia is predicted to perform similarly (forecast 7.1%, 1 MEP). Here again the 2014 EP election seem set – with the exception of Hungary – to confirm the relative weakness of the radical right in Central and Eastern Europe compared to its bastions in Western Europe (France, Denmark, Austria, Finland, Holland)

Interestingly, nowhere in CEE is there any emergence of the intermediate anti-establishment-yet-of-the-establishment right-wing euroscepticism of the type pioneered by UKIP and the Alternative for Germany, occupying no man’s lands between radical right populism and mainstream eurosceptic centre-right conservatism.

Overall, viewed through the prism of East-West difference, the forecasts for upcoming European elections suggest not a political earthquake a basic continuity of long-standing patterns of difference in the party-political landscapes of the ‘old’ West and Southern European EU and the newer post-communist member states – but some surprisingly similarities in trends in support for different party groupings across the two regions of Europe.

Seán Hanley is Senior Lecturer in Comparative Central and East European Politics at UCL-SSEES.

He will be discussing the European elections in Central and Eastern Europe with Eric Gordy (UCL-SSEES), Roxana Mihaila (University of Sussex), Allan Sikk (UCL-SSEES) Aleks Szczerbiak (University of Sussex) at a roundtable event at UCL-SSEES on Monday 19 May, 5.30pm in room 431.

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the SSEES Research blog, nor of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, nor of UCL

2 Responses to “What will the Euro elections tell us about Eastern Europe?”

- 1

-

2

EP Elections: from the library’s campaign notebook (2) | Central Library wrote on 21 May 2014:

[…] at the UCL SSEES looks at differences and similarities in the party landscapes of ‘old’ Member States and the Central and Eastern European […]

Close

Close

[…] Hanley at the UCL SSEES Research Blog assesses how the European elections are likely to play out in Eastern Europe, and what the results might say about the enduring differences between Western and Eastern […]