This review of Otar Iosseliani’s Favourites of the Moon by our Executive Editor Eugenia Ellanskaya recently appeared in the Soviet cinema journal Obskura:

It is 1984 and it’s almost the dusk of the USSR. In other words: high time to submerge into the full cacophony of life’s true diversity and casual perverseness. Favourites of the Moon (Les favoris de la lune) is possibly one of the greatest delicatessens in the alternative Soviet cinema scene. The film’s pretension to an aristocratic and elegant flow is as intricate and disguising as the superficial lifestyles of its characters. Its illusion of beauty and aesthetics seems to hide nothing other than a careless abyss. And guess what? There seems absolutely nothing wrong with that! Embrace the abyss! The movie’s walking-pace speed literally pulls you into a stroll across what seems as random and parallel lives of people, unburdened by thoughts of their long-term ‘destination’ – a suggested happiness recipe in a close-to-apocalypse Soviet society?

Iosseliani is a master architect who builds and tosses around social stratums, giving us surprising combinations of their interaction, which even they aren’t always aware of. An all-penetrating image of a painting and a set of luxury china dinner plates recur throughout the film, taking us from the black and white world of stability to a colourful film of relationship chaos. The black and white images of courting and stern ascetics keep on appearing from time to time alongside the modern timeline, where everything is rushed, stressful and, in the end, truly purposeless. Each social strata has its own philosophy and convincing morals, which are never dwelt on too deeply, but are shown as if at a glimpse of a walker-by.

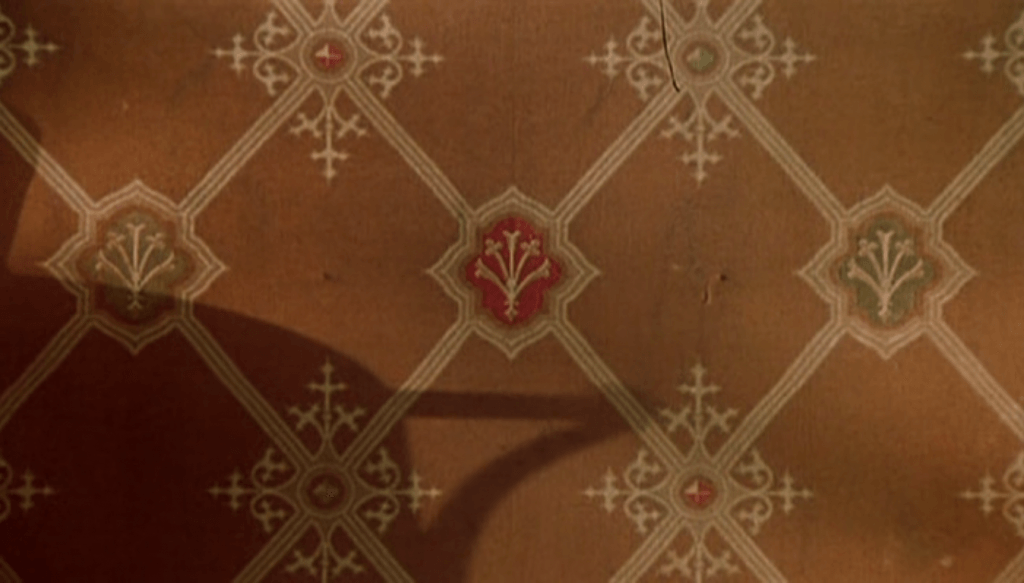

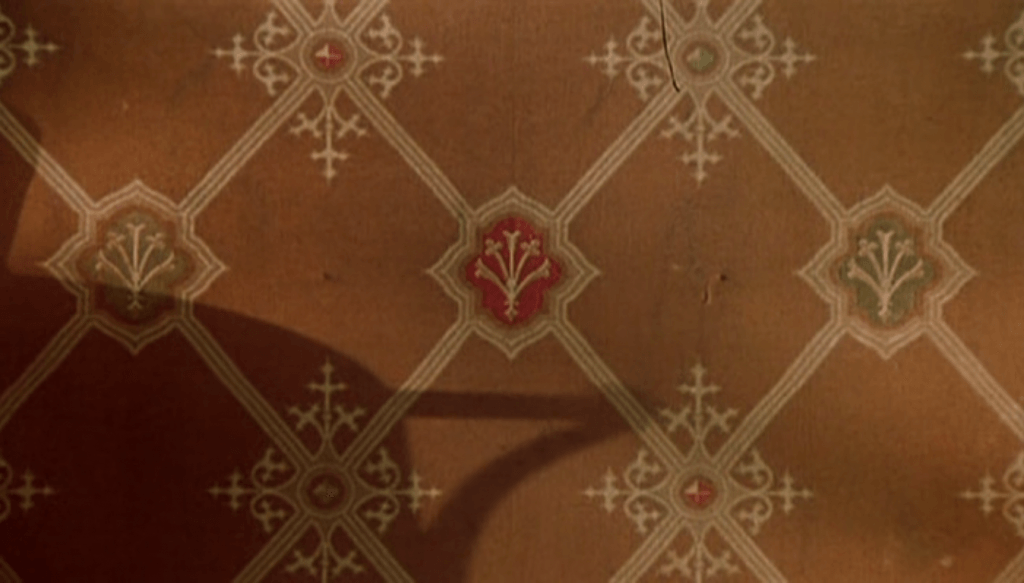

The picturesque black and white world of The Favourites of the Moon

Iosseliani gives each character a chance to take over the objects (the painting and the china dishes) and reveal themselves through it. The ‘upper class’ is gripped in a superficial status-seeking consumption of aesthetics. The illusion the audience too appears involved in… The rich enter an involuntary nostalgia over the aristocratic and genuine 18th century, when the objects were made. They borrow these status props as shamelessly as they rehearse dinner quotes in order to impress their host, and remove socially inconvenient elements, like a disabled family member, from a dinner party. The stressful pace of the diverse colourful world shows people, who are too busy to catch up with the full moral package of the black and white world. But the world has long since been reversed and interrupted by the brief wallpaper still, which is actually full of information:

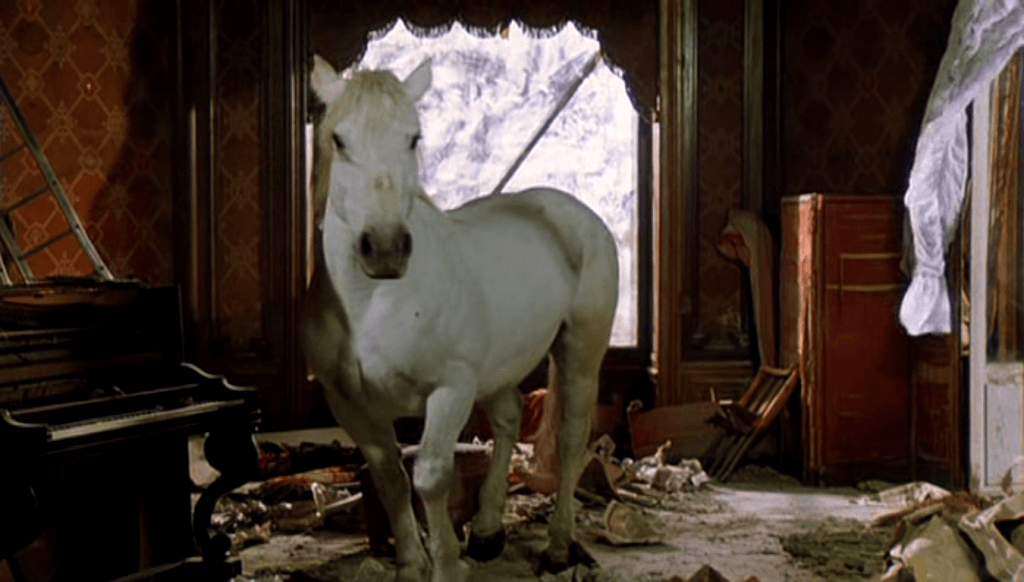

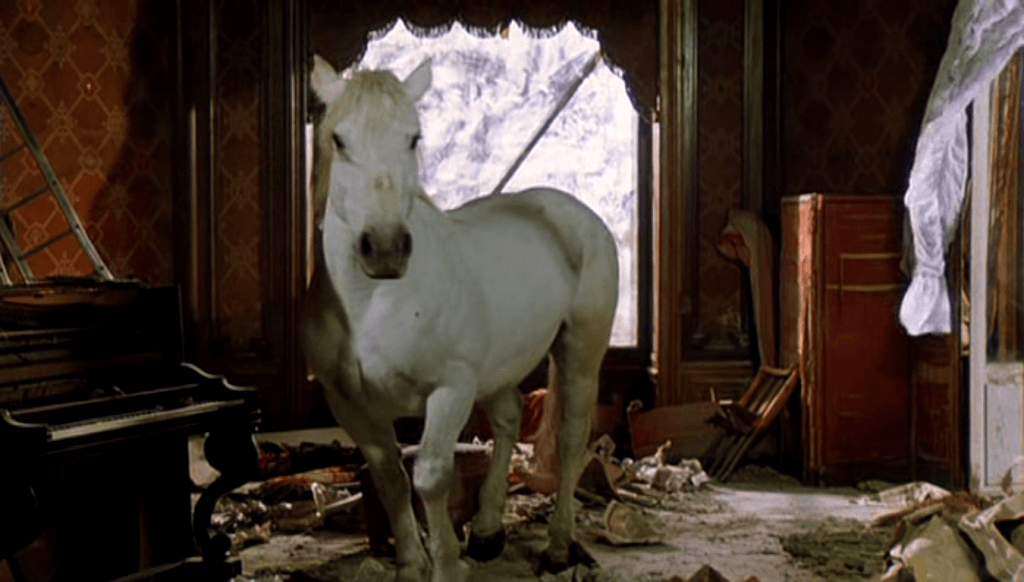

This wallpaper’s soundtrack of shooting and explosions might not necessarily imply a war per se, but a symbolic collapse of the old social order. It is followed by a random appearance of a white horse indoors, which somewhat awkwardly and clumsily stamps on the already familiar broken china plates:

From now on the objects are passed on, modified, broken or stolen…What the rich had broken or lost, forsaking faith in the objects’ repairability, regains its meaning back in the hand of the ‘mob’, the local prostitutes and bin men who try to mend it. This seems symbolic of the hypocrisy and social role play which is never what it seems. In the end, it is the thieves and the prostitutes who are truly loyal to their friends, all sharing a kin relation: the prostitute and thief argue over the “up-bringing” of their “child”, a young thief accomplice.

Although things said remain the same between past and the modern worlds, they surely mean very different things. As the film suggests, the silence the actors are so afraid of breaking in both worlds is at the expense of truth in one case and stupidity in the other. Be it a change of ideology or social paradigms that gives different meaning to silence, we will never know what was unsaid, as both worlds are muted and polluted by worldly chats, as if the director is avoiding direct confrontation… just yet. It is interesting that Iosseliani, a Soviet Georgian, moved to France at the time of the film’s making precisely to avoid Soviet censorship, but is he ready to speak the unspoken? Either way, for now we are expected to continue to admire the aesthetic illusion, which the film is so rich in.

Favourites of the Moon is a provocation. A convincing provocation which asks us to rethink our class conceptions and biases. It upturns our comfortable ideology. It forces us to accept the unexpected niche of nobility amongst the mob and sympathise with the unsympathisable. Like the quote from Shakespeare at the beginning of the film, Iosseliani wants to elevate the prostitutes, tramps and thieves into the new and possibly only domain of hope and nobility, which the rich are only superficially rehearsing. Long live the knights of the night, the favourites of the moon, the whores and the tramps!

As much as everything about this movie promotes excess, class and nonchalance, glorifying form over content, it seems that Iosseliani is also aware of the futility of everything he has glorified in the lifestyles of the characters. It is therefore a caricature, with comic casual explosions, but also seriously perverse social implications of cheating, stealing and so on. And yet Favourites of the Moon is not revolutionary. Neither is it a strong statement. Surprisingly, it is unlike some aggressive Soviet taboo breaking movies. Instead it comes across as a calm and even helpless meditation over the not so great Western reality of the superficial nouveau riche and the romanticised life of the mob. Confronted by the Western reality Iosseliani must have too learnt (or chose?) not to judge, but meditate over this liberal social reality and accept – an attempt to let go of the strong ideological claims and arguments at least for the time being.

Originally published on http://www.obskura.co.uk/favourites-of-the-moon/

Close

Close