Not waving

By uccafau, on 19 January 2015

By 2050, London is likely to be severely in drought. The cause is a combination of growing population, the way we use water and pipe it around our cities and towns, and climate change. If we carry on as we are, there will be a deficit amounting to the water use of 2 million people in a short few decades. On the other hand, risks of water related natural disasters are set to increase, particularly the likelihood of large parts of the UK submerging if all Arctic ice melts. It’s the same story around the globe.

We know all this, and yet as a species we are doing little to address the problem. We protest, we raise awareness, but overall we are still heading for a vastly altered world.

This week, I’m exhibiting my sculpture Not Waving at The Crystal in East London, as part of New Atlantis, an immersive theatre production from LAStheatre. Consisting of 100 miniature people atop 3 miniature icebergs in a bath, an urn and a lot of clever electronics, this interactive installation determines the micro-people’s fate dependent on how much we are chattering about #water on Twitter. Tweet enough and they may survive the show, but if there isn’t enough chatter, water is released from the urn above them – they are drenched and doomed.

The icebergs are made of between 3 and 6 litres of water, which takes quite a while to freeze. Preparations for the sculpture began back in late November, when I started making the moulds for the icebergs with the help of prop-maker Ben Palmer. Once the moulds were ready, I brought them to UCL’s Ice Physics lab where the icebergs were frozen over the course of the last 2 months by Ben Lishman, of UCL’s Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction, who’s also appearing in the show.

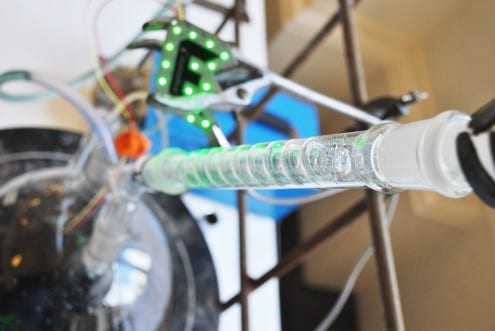

Next came the electronics – a Raspberry Pi and servo hacked into a water urn. This rig talks to the internet and controls the urn’s tap, releasing water when there has been insufficient tweeting about #water. What’s insufficient? Well, I worked out an average number of tweets per 10 minutes across an evening, and set it at just above that mark – 50 per 10 minutes. This is all connected up to a screen, programmed with the help of Jun Matsushita to look like this:

Of course, the secret is that the fate of our 100 micro-people is sealed: the urn will empty into the bath at the end of the show. Because it turns out social media chatter doesn’t change our fate – we need to act here in the physical, real world. The one in which the water is wet, the ice is melting, and the little people are struggling to stay dry.

Of course, the secret is that the fate of our 100 micro-people is sealed: the urn will empty into the bath at the end of the show. Because it turns out social media chatter doesn’t change our fate – we need to act here in the physical, real world. The one in which the water is wet, the ice is melting, and the little people are struggling to stay dry.

That’s the reason the drowning is staged in a bath, with a hot-water urn above it, and tweets scrolling on a screen above that. All these activites – heating and processing water, and our endless online activity – they have a carbon footprint. They are all contributing to climate change.

That’s the reason the drowning is staged in a bath, with a hot-water urn above it, and tweets scrolling on a screen above that. All these activites – heating and processing water, and our endless online activity – they have a carbon footprint. They are all contributing to climate change.

Happily, we aren’t at the end of the show yet – and New Atlantis gives the audience the opportunity to learn about how we might deal with water stress in the future – and make decisions within the world of New Atlantis about how we might move forward.

Lots of the details of production are on my blog, and if you’re thinking of doing something similar I’d be very happy to tell you more of what I’ve learned. I also explain a bit more about it in this interview for iScience.

If you’d like to check it out, New Atlantis runs until the 25th January at The Crystal.

Kat Austen is Artist in Residence at UCL Faculty of Mathematical & Physical Sciences

Close

Close