Rosetta: The best ever opportunity to study a comet

By Oli Usher, on 7 July 2014

The European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission, coming to its climax only now, a decade after launch, will have a number of scientific firsts: the first probe to follow a comet around the Sun while it orbits, the first to orbit a cometary nucleus, and the first to deploy a lander on the comet’s surface.

UCL has made a major contribution to the scientific programme the spacecraft, thanks to its long-standing expertise in plasma physics. Much of this expertise was gained in a previous space mission.

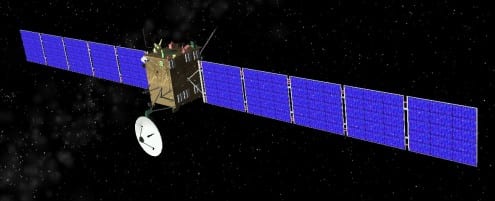

Artist’s concept of the Giotto spacecraft approaching Comet Halley. Credit: Andrzej Mirecki (CC-BY-SA 3.0)

In 1986, the Giotto probe flew by Comet Halley, giving the first ever close-up view of a comet’s nucleus. UCL built the probe’s Fast Ion Sensor and led the Johnstone Plasma Analyser team. Thanks to this detector, scientists were able to study the interaction between the comet and the solar wind as the comet ploughed through it, including the enormous bow-shock in front of the comet that extended for around a million kilometres, and the processes by which cometary ions are ‘picked up’ by the solar wind.

Rosetta should give us a lot more than this. Two decades of technological progress mean sharper photos and more sensitive instruments. But the major improvement is in how long the probe will be able to study the comet for, as well as its close-up study of the comet’s ionosphere. Giotto made only a relatively short flyby of Halley, in large part because the comet’s orbit is highly inclined and moves in the opposite direction to Earth’s, and it only passes through the plane of the Solar System on two brief occasions every 76 years. Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko, Rosetta’s target, is in an orbit that is easier to rendezvous with, which means – with some admittedly difficult and time-consuming orbital mechanics – Rosetta can be brought into orbit around it.

This, in turn, means the changes in the comet, including the growth of its coma, and plasma (gas) and dust tails, can be charted in detail as it proceeds around the Sun.

UCL scientists at the Mullard Space Science Laboratory are particularly closely involved in the Rosetta Plasma Collaboration, a scientific group which will study the electrical properties of the comet as it interacts with the Solar wind. This is a direct continuation of the work done with Giotto nearly three decades ago.

The wait won’t be long now – Rosetta is less than 30,000km from its goal (less than the distance between Earth and geostationary communications satellites), and will begin manoeuvring into orbit in early August. Early data will come sooner, with the first detection of the comet’s plasma expected perhaps as early as this week.

Rosetta is one of a number of missions being discussed at the Alfvén Conference this week at UCL. Named after Hannes Alfvén, a Swedish plasma physicist and Nobel laureate, the conference is bringing together experts from around the world in the field of Solar System plasma interactions, such as those Rosetta will study.

As part of the conference, Matt Taylor, the scientific leader of the Rosetta project will be giving a public lecture tomorrow (Tuesday 8 July) at 6pm. He will outline the probe’s amazing ten year journey, outline Rosetta’s scientific goals and explain why comets are such an important window into the distant past of our Solar System. The lecture is free and open to all, but please reserve your seat as spaces are limited.

Close

Close