Stress in Non-Human Animals

By Stacy Hackner, on 14 October 2015

This post is associated with our exhibit Stress: Approaches to the First World War, open October 12-November 20.

This post is associated with our exhibit Stress: Approaches to the First World War, open October 12-November 20.

A pig’s skull may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of stress. You may not think of non-human animals at all. However, humans are not the only animals that experience stress and related emotions. Many of the behaviors associated with human psychological disorders can be seen in domestic animals. Divorced from the dialogue of consciousness and cognition, animals have been seen exhibiting symptoms of depression, mourning, and anxiety. Wild animals in captivity ranging from elephants to wolves have exhibited signs of post-traumatic stress disorder; this is also an argument for why orcas in captivity suddenly turn violent. According to noted animal behaviorist Temple Grandin, animals that live in impoverished environments or are prevented from performing natural behaviors develop “stereotypic behaviors” such as rocking, pacing, biting the bars of their enclosure or themselves, and increased aggression. Many of these bear similarities to individuals with a variety of psychological conditions, and (most interestingly) when given psychopharmaceuticals, the behaviors cease.

The First World War unleashed horrors on human soldiers, resulting in shell shock (now called PTSD). However, many animals were also used, including more than one million horses on the Allied side, mostly supplied by the colonies – but 900,000 did not return home. Mules and donkeys were also used for traction and transport, and dogs and pigeons were used as messengers. (Actually, the Belgians used dogs to pull small wagons.) Since the advent of canning in the 19th century, armies no longer had to herd their food along, but apparently the Gloucestershire Regiment brought along a dairy cow to provide fresh milk, although she may have served as a regimental mascot as well – some units kept dogs and cats too.

Horses in gas masks. Sadly, they often confused these with feed bags and proceeded to eat them. Credit Great War Photos.

The RSPCA set up a fund for wounded war horses and operated field veterinary hospitals. They treated 2.5 million animals and returned 85% of those to duty. 484,143 British large animals were killed in combat, which is roughly half the number of British soldiers killed. Estimates place the total number of horses killed at around 8 million.

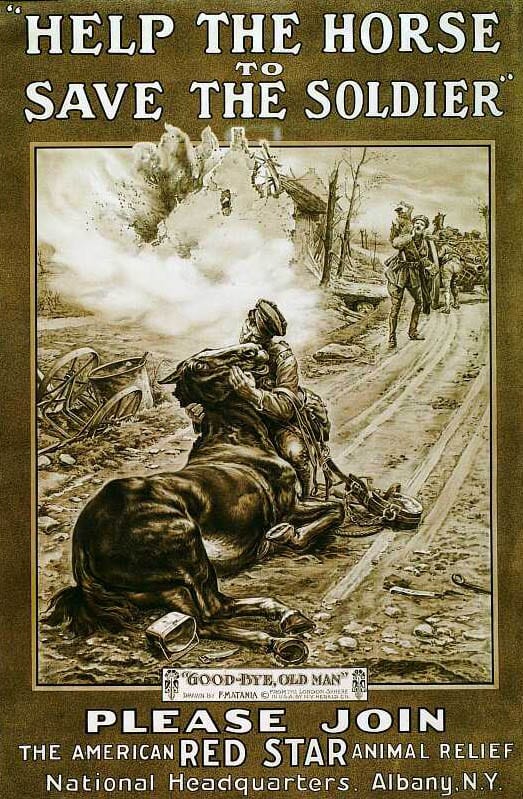

The horses in particular had a strong impact on the soldiers. Researcher Jane Flynn points out that a positive horse-rider relationship was imperative for both on the battlefield. She cites a description of the painting Goodbye Old Man:

“Imagine the terror of the horse that once calmly delivered goods in quiet suburban streets as, standing hitched to a guncarriage amid the wreck and ruin at the back of the firing line, he hears above and all around him the crash of bursting shells. He starts, sets his ears back, and trembles; in his wondering eyes is the light of fear. He knows nothing of duty, patriotism, glory, heroism, honour — but he does know that he is in danger.”

“Goodbye, Old Man” used in a poster. Credit RSPCA.

Historical texts tend to consider horses and other animals used in war as equipment secondary to humans, and even the RSPCA only covers their physical health. Horses don’t only have relationships with their riders, but with the other horses nearby and with the environment. They can easily be frightened by loud noises, not to mention explosions, ground tremors from trench cave-ins, and other things that scared humans sharing their situation. Many horse owners (many pet owners, in fact) argue that their horses have and express human-like emotions. Even if we can’t verify this scientifically, we can observe that horses experience fear, rage, confusion, gain, loss, happiness and sadness. Grandin argues that horses have the capacity to experience and express these simple emotions as well as recall and react to past experiences, but are unable to rationalize these emotions: they simply feel. It’s impossible to say whether that makes it more frightening for a horse or a human to wade through a field of dead comrades. In Egypt, I took a horse ride around the pyramids. The trail led us through what turned out to be an area of the desert where stable owners execute their old horses, resulting in a swath of rotting corpses. I was shocked, and my horse displayed all the signs of fear: ears pinned back, wide eyes, tensed muscles. He recovered after we’d left the area, but I wondered what psychological impact having that experience day after day would cause. If they are able to remember frightening experiences, they might be able to experience post-traumatic stress and be as shell-shocked as the returning soldiers. British soldiers reported that well-bred horses experienced more “shell-shock” than less-pedigreed stock, bolting, stampeding, and going berserk on the battlefield – all typical behaviors of horses under duress, – but did not elaborate on the long-term consequences of this behavior. It would be interesting to explore accounts of horses that survived the war (and were returned to their original owners instead of being sold in Europe or slaughtered) to see whether they exhibited more stereotypical behaviors of stress and shell-shock just as human soldiers did.

Sources

Thanks to Anna Sarfaty for advice.

Animals in World War One. RSPCA.org.

Bekoff, Mark. Nov 29, 2011. Do wild animals suffer from PTSD and other psychological disorders? Psychology Today (online).

Flynn, Jane. 2012. Sense and sentimentality: a critical study of the influence of myth in portrayals of the soldier and horse during World War One. Critical Perspectives on Animals in Society: Conference Proceedings.

Grandin, Temple and Johnson, Catherine. 2005. Animals in Translation: Using the Mysteries of Autism to Decode Animal Behavior. New York: Scribner.

Shaw, Matthew. ND. Animals and war. British Library Online: World War One.

Tucker, Spencer C. (ed.) 1996. The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland.

Close

Close