Did we evolve to run?

By Stacy Hackner, on 5 January 2015

A few years ago, spurred by my research on just how deleterious the sedentary lifestyle of a student can be on one’s health, I decided to start running. Slowly at first, then building up longer distances with greater efficiency. A few months ago, I ran a half-marathon. At the end, exhausted and depleted, I wondered: why can we do this? Why do we do this? What makes humans want to run ridiculous distances? A half-marathon isn’t even the start – there are people who do full marathons back-to-back, ultra-marathons of 50 miles or more, and occasionally one amazing individual like Zoe Romano, who surpassed all expectations and ran across the US and then ran the Tour de France.[i] Yes, ran is the correct verb – not cycled.

I’ve met so many people who tell me they can’t run. They’re too ungainly, their bums are wobbly, they’re worried about their knees, they’re too out of shape. Evolution argues otherwise. There are a number of researchers investigating the evolutionary trends for humans to be efficient runners, arguing that we are all biomechanically equipped to run (wobbly bums or not). If you have any question whether you can or can not run, just check out the categories of races in the Paralympic Games. For example, the T-35 athletics classification is for athletes with impairments in ability to control their muscles; in 2012, Iiuri Tsaruk set a world record for the 200m at 25.86s, which is only 6 seconds off Bolt’s world record at 19.19 and 4 seconds off Flo-Jo’s womens record (doping aside). 2012 also saw the world record for an athlete with visual impairment: Assia El Hannouni ran 200m in 24.46.[ii] You try running that fast. Now try running with significant difficulty controlling your limbs or seeing. If you’re impressed, think about these athletes the next time you say you can’t run.

Let’s think about bipedalism for a bit. Which other animals walk on two legs besides us? Birds, for a start, although flight is usually the primary mode of transport for all except penguins and ostriches. On the ground, birds are more likely to hop quickly than to walk or run. Kangaroos also hop. Apes are able to walk bipedally, but normally use their arms as well. Cockroaches and lizards can get some speed over short distances by running on their back legs. However, humans are different as we always walk on two legs, keep the trunk erect rather than bending forward as apes do, keep the entire body relatively still, and use less energy due to stored kinetic energy in the tendons during the gait.[iii] Apparently we can group our species of strange hairless apes into the category “really weird sorts of locomotion” along with kangaroos and ostriches.

Following this logic, Lieberman et al point out that a human could be bested in a fight with a chimp based on pure strength and agility, can easily be outrun by a horse or a cheetah in a 100m race, and have no claws or sharp teeth: “we are weak, slow, and awkward creatures.”[iv] We do have two strokes in our favor, though – enhanced cognitive capabilities and the ability to run really long distances. Our being awkwardly bipedal naked apes actually helps more than one would think. First, bipedalism decouples breathing from stride. Imagine a quadruped running – as the legs come together in a gallop, the back arches and forces the lungs to exhale like a bellows. Since humans are upright, the motion of our legs doesn’t necessarily affect our breathing pattern. Second, we sweat in order to cool down during physical exertion. (In particular, I sweat loads.) Panting is the most effective way for a hairy animal to cool down, as hair or fur traps sweat and doesn’t allow for effective convection (imagine standing in a cool breeze while covered in sweat – this doesn’t work for a dog.) But it’s impossible to pant while running. So not only are humans able to regulate breathing at speed, but we can cool down without stopping for breath.

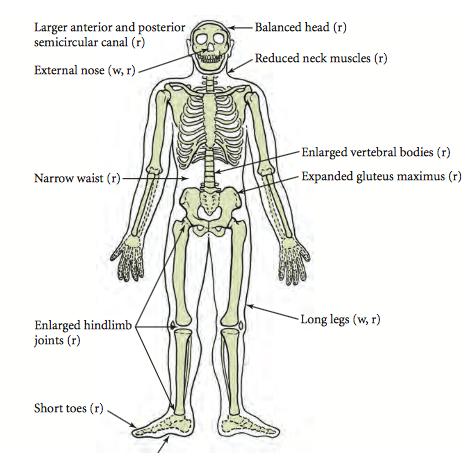

From a purely skeletal perspective, there is more evidence for the evolution of running. Human heads are stabilized via the nuchal ligament in the neck, which is present only in species that run (and some with particularly large heads), and we have a complex vestibular system that becomes immediately activated to ensure stability while running. The insertion on the calcaneus (heel bone) for the Achilles tendon is long in humans, increasing the spring action of the Achilles.[v] Humans have relatively long legs and a huge gluteus maximus muscle (the source of the wobbly bum). All of these changes are seen in Homo erectus, which evolved 1.9 million years ago.[vi]

H. erectus skeleton with adaptations for running (r) and walking (w). From Lieberman 2010.

The evolutionary explanation for this is the concept of endurance or persistence hunting. In a hot climate, ancient Homo could theoretically run an animal to death by inducing hyperthermia. This is also where we come full circle and bring in the cognitive capabilities of group work. A single individual can’t chase an antelope until it expires from heat stroke because it’ll keep going back into the herd and then the herd will scatter. But a team of persistence hunters can. If persistence hunting is how humans (or other Homo species) evolved to be great at long distance running, that’s also the why humans developed larger brains: the calories in meat generated an excess of calories that allowed nourishment of the great energy-suck that is the brain. However, persistence hunting is a skill that mostly went by the wayside as soon as projectile weapons (arrowheads and spears) were invented, possibly around 300,000 years ago. Why? Because humans, due to our large brains, are very inventive, but also very lazy. Any expenditure of energy must be made up for by calories consumed later, at least in a hunting and gathering environment – so less energy output means less energy input; a metabolic balance. Thus we have the reason why humans can run, but also why we don’t really want to. (As an aside, some groups such as the Kalahari Bushmen practiced persistence hunting until recently, although they had projectile weapon technology, probably because of skill traditions and retaining cultural practices. Humans are always confounding like that.)

Which brings up another point: gathering. As I’ve written before, contemporary hunter-gatherers like the Hadza rely much more on gathering than hunting. Additionally, it is possible that the first meat eaten by Homo species was scavenged rather than hunted. There is no such evolutionary argument as endurance gathering. If ancient humans spent much more time gathering, why would we evolve these particular running mechanisms? As with many queries into human evolution, these questions have yet to be answered. Either way, it’s clear that humans have a unique ability. Your wobbly bum is, in fact, the key to your running. Another remaining question is why we still have the desire to continue running these ridiculous distances – a topic for a future post, perhaps.

Sources

[i] http://www.zoegoesrunning.com

[ii] Check out all the records at http://www.paralympic.org/results/historical

[iii] Alexander, RM. Bipedal Animals, and their differences from humans. J Anat, May 2004: 204(5), 321-330.

[iv] Lieberman, DE, Bramble, DM, Raichlen, DA, Shea, JJ. 2009. Brains, Brawn, and the Evolution of Human Endurance Running Capabilities. In The First Humans – Origins and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo (Grine, FE, Fleagle, JG, Leakey, RE, eds.) New York: Springer, pp 77-98.

[v] Raichlen, DA, Armstrong, H, Lieberman, DE. 2011. Calcaneus length determines running economy: implications for endurance running performance in modern humans and Neandertals. J Human Evol 60(3): 299-308.

[vi] Lieberman, DE. 2010. Four Legs Good, Two Legs Fortuitous: Brains, Brawn, and the Evolution of Human Bipedalism. In In the Light of Evolution (Jonathan B Losos, ed.) Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts & Co, pp 55-71.

7 Responses to “Did we evolve to run?”

- 1

- 2

- 3

-

4

Why Talk to Engagers? | UCL Researchers in Museums wrote on 9 February 2015:

[…] by Stacy Hackner […]

-

5

Did we evolve to run? | Stacy Hackner wrote on 19 September 2016:

[…] published on Student Engagers on January 15, […]

-

6

Sports in the Ancient World | UCL Researchers in Museums wrote on 24 January 2017:

[…] written previously here about the antiquity of running, which was one of the original sports at the ancient Greek Olympics, […]

-

7

Sports in the Ancient World | Stacy Hackner wrote on 24 January 2017:

[…] written previously here about the antiquity of running, which was one of the original sports at the ancient Greek Olympics, […]

Close

Close

Actually there are a number of other flightless birds such as emus, kiwis, and a few other ratites