A[got]chu! Surviving the Flu

By Sarah Savage Hanney, on 2 December 2013

As the temperature drops and the wind blows harshly through the wind tunnels of the Tube, it genuinely feels like winter in London! When visitors arrive in the UCL museums blowing their noses and smelling of Strepsils, I am yet again reminded it is cold and flu season.

When I discuss my research on the Spanish Influenza and Encephalitis Lethargica epidemics, one of the first responses I get from visitors is: “So you’re a medical doctor, right? How can I treat [insert ailment]?” Unfortunately I am not licenced nor qualified to give such advice; however, I can discuss from a historical perspective what treatments have worked and not worked for illnesses ranging from the common cold to malaria.

Throughout the history of medicine, societies have sought to find more effective and fool-proof treatments for everyday illnesses. Simple home remedies such as tying a bulb of garlic around the neck to ward off insects (potentially carrying an infectious disease such as malaria) and drinking water rich in minerals for health have existed for thousands of years and are practiced consciously or subconsciously still today. Even the types of vitamins we consume, including vitamin C and zinc, to prevent and cure colds, are influenced by this inherited medical knowledge passed down from generation to generation.

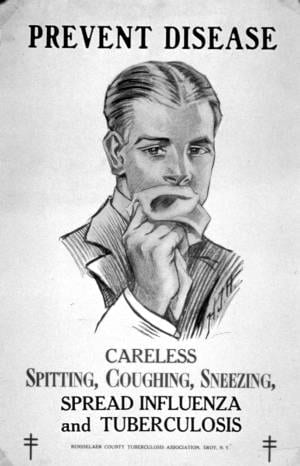

Perhaps the most frequently asked question I receive is: “How do I prevent influenza?” The short answer is, you can’t. Since influenza is a viral infection that spreads through transmission in human contact or infected surface contact, it is very difficult to live in a virus-free zone. Especially in London where travellers sneeze openly in trains and residents rely upon communal areas for business and pleasure, we are flu-prone.

However, what are some ways that Londoners a hundred years ago combatted the same illnesses we suffer with today? In the early 20th century, medicine was as much preventative as it was curative. Diet was an essential tool that families used as part of inherited medicinal knowledge [think of your mother’s advice]. Certain foods including milk, citrus, and broths became the main ‘sick foods’ during the 1918 Spanish Influenza epidemic in England alongside fever reducers, purgatives, and even morphine. In addition to the prescribed manufactured drugs, residents also turned to older recipes to combat the initial signs of the flu. Dried flowers, including nettle, would have been used to make teas, while crushed herbs, such as mint, could be applied with a salve to the chest to improve breathing.

Although medical professionals did not understand the cause or spread of influenza viruses in 1918, boards of health throughout England closed public spaces of leisure and business to prevent human-to-human transmission of the killer flu. Despite public health departments’ attempts to isolate and quarantine populations across the globe, an estimated 20 to 50 million died worldwide. Since influenza commonly has a three to five day incubation period (when the virus becomes settled in your body) before a patient begins showing symptoms, it is naturally difficult to isolate all infected persons to prevent spread to the healthy. As medicine advances further and we develop more complex, powerful vaccinations, it is possible that illnesses such as the common flu will become less common, or at least less severe.

From looking at past influenza epidemics, the best tips are:

- Self-quarantine!

- Maintain a healthy diet both before and during illness

- Avoid public transport during an outbreak

- Stay at home if you are feeling ill

- Use fresh supplies when tending to the ill (boil utensils, wash bedding and clothing at a high temperature, etc.)

- Always give an ill patient ample ventilation

- If someone begins bleeding from the eyes (as in the case of Spanish Flu), it’s best to move down to the next train car

For more information concerning helpful tips during Flu season, visit the NHS, World Health Organization, and Centre for Disease Control websites.

Close

Close