UCL open access output: 2023 state-of-play

By Kirsty, on 15 April 2024

Post by Andrew Gray (Bibliometrics Support Officer) and Dominic Allington Smith (Open Access Publications Manager)

Summary

UCL is a longstanding and steadfast supporter of open access publishing, organising funding and payment for gold open access, maintaining the UCL Discovery repository for green open access, and monitoring compliance with REF and research funder open access requirements. Research data can be made open access in the Research Data Repository, and UCL Press also publish open access books and journals.

The UCL Bibliometrics Team have recently conducted research to analyse UCL’s overall open access output, covering both total number of papers in different OA categories, and citation impact. This blog post presents the key findings:

- UCL’s overall open access output has risen sharply since 2011, flattened around 80% in the last few years, and is showing signs of slowly growing again – perhaps connected with the growth of transformative agreements.

- The relative citation impact of UCL papers has had a corresponding increase, though with some year-to-year variation.

- UCL’s open access papers are cited around twice as much, on average, as non-open-access papers.

- UCL is consistently the second-largest producer of open access papers in the world, behind Harvard University.

- UCL has the highest level of open access papers among a reference group of approximately 80 large universities, at around 83% over the last five years.

Overview and definitions

Publications data is taken from the InCites database. As such, the data is primarily drawn from InCites papers attributed to UCL, filtered down to only articles, reviews, conference proceedings, and letters. It is based on published affiliations to avoid retroactive overcounting in past years: existing papers authored by new starters at UCL are excluded.

The definition of “open access” provided by InCites is all open access material – gold, green, and “bronze”, a catch-all category for material that is free-to-read but does not meet the formal definition of green or gold. This will thus tend to be a few percentage points higher than the numbers used for, for example, UCL’s REF open access compliance statistics.

Data is shown up to 2021; this avoids any complications with green open access papers which are still under an embargo period – a common restriction imposed by publishers when pursuing this route – in the most recent year.

1. UCL’s change in percentage of open access publications over time

The first metric is the share of total papers recorded as open access. This has grown steadily over time over the last decade, from under 50% in 2011 to almost 90% in 2021, with only a slight plateau around 2017-19 interrupting progress.

2. Citation impact of UCL papers over time

(InCites all-OA count, Category Normalised Citation Impact)

The second metric is the citation impact for UCL papers. These are significantly higher than average: the most recent figure is above 2 (which means that UCL papers receive over twice as many citations as the world average; the UK university average is ~1.45) and continue a general trend of growing over time, with some occasional variation. Higher variation in recent years is to some degree expected, as it takes time for citations to accrue and stabilise.

3. Relative citation impact of UCL’s closed and Open Access papers over time

(InCites all-OA count, Category Normalised Citation Impact)

The third metric is the relative citation rates compared between open access and non-open access (“closed”) papers. Open access papers have a higher overall citation rate than closed papers: the average open access paper from 2017-21 has received around twice as many citations as the average closed paper.

4. World leading universities by number of Open Access publications

Compared to other universities, UCL produces the second-highest absolute number of open access papers in the world, climbing above 15,000 in 2021, and has consistently been the second largest publisher of open access papers since circa 2015.

The only university to publish more OA papers is Harvard. Harvard typically publishes about twice as many papers as UCL annually, but for OA papers this gap is reduced to about 1.5 times more papers than UCL.

5. World leading universities by percentage of Open Access publications

(5-year rolling average; minimum 8000 publications in 2021; InCites %all-OA metric)

UCL’s percentage of open access papers is consistently among the world’s highest. The most recent data from InCites shows UCL as having the world’s highest level of OA papers (82.9%) among institutions with more than 8,000 papers published in 2021, having steadily risen through the global ranks in previous years.

Conclusion

The key findings of this research are very good news for UCL, indicating a strong commitment by authors and by the university to making work available openly. Furthermore, whilst high levels of open access necessarily lead to benefits relating to REF and funder compliance, the analysis also indicates that making research outputs open access leads, on average, to a greater number citations, providing further justification for this support, as being crucial to communicating and sharing research outcomes as part of the UCL 2034 strategy.

Get involved!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, LinkedIn, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, LinkedIn, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

How understanding copyright can help you as a researcher

By Rafael, on 4 April 2024

Guest post by Christine Daoutis, Copyright Support Officer

Welcome to the inaugural blog post of a collaborative series between the UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship and the UCL Copyright team. In this series, we will explore important aspects of copyright and its implications for open research and scholarship.

Research ideas, projects, and their outcomes often involve using and producing materials that may be protected by copyright. Copyright protects a range of creative works, whether we are talking about a couple of notes in a notebook, a draft thesis chapter, the rough write-up of a data, a full monograph and the content of this very blog. While a basic knowledge of copyright is essential, particularly to stay within the law, there is much more to copyright than compliance. Understanding certain aspects of copyright can help you use copyright materials with more confidence, make use of your own rights and overall, enhance the openness of your research.

Image attribution: Patrick Hochstenbach, 2014. Available under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This first post in our series is dedicated to exploring common questions that arise during research projects. In future posts, we will explore some of these questions further, providing guidance, linking to new resources, and signposting relevant workshops. Copyright-related enquiries often arise in the following areas:

Reusing other people’s materials: How do you GET permission to reuse someone else’s images, figures, software, questionnaires, or research data? Do you always need permission? Is use for ‘non-commercial, research’ purposes always permitted, or are there other factors to consider? How do licenses work, and what can you do when a license does not cover your use? It’s easy to be overconfident when using others’ materials, for example, by assuming that images found on the internet can be reused without permission. It’s equally easy to be too cautious, ending up not making use of valuable resources for fear of infringing someone’s rights. Understanding permissions, licenses, and copyright exceptions – what may be within your rights to do as a user – can help you.

Disseminating your research throughout the research cycle: There are open access options for your publications and theses, supporting access to and often, reuse of your work. How do you license your work for reuse? What do the different licenses mean, and which one is most suitable? What about materials produced early on in your research: study preregistrations, research data, preprints? How can you make data FAIR through licensing? What do you need to consider when making software and other materials open source?

Is your work protected in the first place? Documents, images, video and other materials are usually protected by copyright. Facts are not. For a work to be protected it needs to be ‘original’. What does ‘original’ mean in this context? Are data protected by copyright? What other rights may apply to a work?

Who owns your research? We are raising questions about licensing and disseminating your research, but is it yours to license? What does the law say, and what is the default position for staff and students at UCL? How do contracts, including publisher copyright transfer agreements and data sharing agreements, affect how you can share your research?

‘Text and data mining’. Many research projects involve computational analysis of large amounts of data. This involves copying and processing materials protected by copyright, and often publishing the outcomes of this analysis. In which cases is this lawful? How do licences permit you to do, exactly, and what can you do under exceptions to copyright? How are your text and data mining activities limited if you are collaborating with others, across institutions and countries?

The use of AI. Speaking of accessing large amounts of data, what is the current situation on intellectual property and generative AI? What do you need to know about legal implications where use of AI is involved?

These questions are not here to overwhelm you but to highlight areas where we can offer you support, training, and opportunities for discussion. To know more:

- Follow future posts on this blog.

- Register for an upcoming copyright session. If you cannot make those dates, please contact copyright@ucl.ac.uk to arrange a bespoke session.

- Visit our training and resources page for more ideas and links to online tutorials.

- Have a head start: visit our guidance on copyright and publications, copyright and research data and look out for upcoming guidance on text and data mining.

Get involved!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, LinkedIn, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, LinkedIn, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

Call for Papers & Posters – UCL Open Science Conference 2024

By Rafael, on 21 March 2024

Theme: Open Science & Scholarship in Practice

Date: Thursday, June 20th, 2024 1-5pm, followed by Poster display and networking

Location: UCL Institute of Advanced Studies, IAS Common Ground room (G11), South Wing, Wilkins Building

We are delighted to announce the forthcoming UCL Open Science Conference 2024, scheduled for June 20, 2024. We are inviting submissions for papers and posters showcasing innovative practices, research, and initiatives at UCL that exemplify the application of Open Science and Scholarship principles. This internally focused event aims to showcase the dynamic landscape of Open Science at UCL and explore its practical applications in scholarship and research, including Open Access Publishing, Open Data and Software, Transparency, Reproducibility, Open Educational Resources, Citizen Science, Co-Production, Public Engagement, and other open practices and methodologies. Early career researchers and PhD students from all disciplines are particularly encouraged to participate.

Conference Format:

Our conference will adopt a hybrid format, offering both in-person and online participation options, with a preference for in-person attendance. The afternoon will feature approximately four thematic sessions, followed by a poster session and networking opportunities. Session recordings will be available for viewing after the conference.

Call for papers

Submission Guidelines:

We invite all colleagues at UCL to submit paper proposals related to Open Science and Scholarship in Practice, some example themes are below. Papers could include original research, case studies, practical implementations, and reflections on Open Science initiatives. Submissions should adhere to the following guidelines:

- Abstracts: Maximum 300 words

- Presentation Length: 15 minutes (including time for questions)

- Deadline for Abstract Submission: Friday, April 26

Please submit your abstract proposals using this form.

Potential Subthemes:

- Case Studies and Best Practices in Open Science and Scholarship

- Open Methodologies, Transparency, and Reproducibility in Research Practices

- Open Science Supporting Career Development and Progression

- Innovative Open Data and Software Initiatives

- Promoting and Advancing Open Access Publishing within UCL

- Citizen Science, Co-Production, and Public Engagement Case Studies

- Open Educational Resources to Support Teaching and Learning Experiences

Call for Posters

Session Format:

The poster session will take place in person during the evening following the afternoon conference. Posters will be displayed for networking and engagement opportunities. Additionally, posters will be published online after the conference, potentially through the Research Data Repository. All attendees are encouraged to participate in the poster session, offering a platform to present their work and engage in interdisciplinary discussions.

Submission Guidelines:

All attendees are invited to propose posters showcasing their work related to Open Science and Scholarship in Practice. Posters may include research findings, project summaries, methodological approaches, and initiatives pertaining to Open Science and Scholarship.

Deadline: Friday, May 24

Please submit your poster proposals using this form.

Next Steps

Notifications of acceptance will be sent in the week ending May 10th for Papers and June 7th for Posters.

Recordings of the UCL Open Science Conference 2023, are available on this blog post from May 2023.

For additional information about the conference or the calls, feel free to reach out to us at openscience@ucl.ac.uk.

Watch this space for more news and information about the upcoming UCL Open Science Conference 2024!

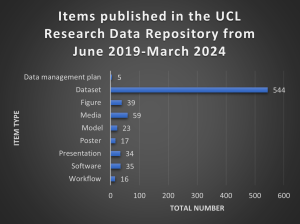

From Seed to Blossom: Reflecting on Nearly 5 Years of the UCL Research Data Repository

By Rafael, on 13 March 2024

Guest post by Dr Christiana McMahon, Research Data Support Officer

In June 2019, the Research Data Management team from Library Services and the Research Data Group from the Centre for Advanced Research Computing embarked on an exciting journey: the launch of the UCL Research Data Repository. As we approach our fifth anniversary, we find ourselves reflecting on the progress we’ve made, what we’ve achieved and what could be improved. To better understand the impact and gather insights from our UCL community, we invite you to complete this survey here. Join us in celebrating this important milestone!

Since its inception, the Research Data Repository has been a pivotal tool for openness and accessibility, offering UCL staff and research students a platform to archive, publish, and share their research outputs as widely and openly as possible. From datasets to figures, presentations to software, the repository has become a hub of scholarly exchange and collaboration. The journey thus far has been marked by significant milestones. Since 2019, we’ve seen over 385,000 downloads and 610,000 views, underscoring the repository’s impact and reach within the academic community.

The Research Data Repository enables users to:

- archive and preserve research outputs on a longer-term basis at UCL;

- facilitate the discovery and sharing of work by publishing metadata records;

- assign a digital object identifier (DOI) to permanently link to and identify a record in the online catalogue as part of a full data citation enabling others to reference published works;

- comply with the UCL Research Data policy and other applicable research policies.

Three highlights from the Research Data Repository:

The most viewed record is: Silvester, Christopher; Hillson, Simon (2019). Photographs used for Structure from Motion 3D Dental model generation Part 2. University College London. Figure. https://doi.org/10.5522/04/9939419

The most downloaded record is: Acton, Sophie; Kriston-Vizi, Janos; Singh, Tanya; Martinez, Victor (2019). RNA seq – PDPN/CLEC-2 transcription in FRCs. University College London. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.5522/04/9976112.v1

The most cited record is: Manescu, Petru; Shaw, Mike; Elmi, Muna; Zajiczek, Lydia; Claveau, Remy; Pawar, Vijay; et al. (2020). Giemsa Stained Thick Blood Films for Clinical Microscopy Malaria Diagnosis with Deep Neural Networks Dataset.. University College London. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.5522/04/12173568.v1

These milestones demonstrate the repository’s impact and reach within the academic community, serving as a testament to the collaborative efforts of our dedicated researchers and staff.

Why is the Research Data Repository essential to supporting academic communities across UCL?

It mostly stems from wanting researchers to manage and share their outputs in line with the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) and embrace open science and scholarship practices. Essentially, by depositing outputs into the Research Data Repository and creating associated metadata records, other researchers and members of the public are better placed to find, understand, combine, and reuse the outputs of our research without major technical barriers. In turn, this can help to enhance transparency of the research process, promote enhanced research integrity, and ultimately maximise the value of research findings.

Going forward:

To continue building and developing the service, we are asking staff and research students to tell us what they think. What works well? What could be improved? Which functionalities would you like to see added or enhanced?

The survey closes on Friday, March 22nd, so get in touch and tell us what you think!

Survey link: https://forms.microsoft.com/e/U20yJPAi0W

More information about the Research Data Repository can be found in Open Science & Research Support dedicated webpage.

Any questions or queries about the Research Data Repository can be sent to: researchdatarepository@ucl.ac.uk.

General research data management queries can be sent to: lib-researchsupport@ucl.ac.uk.

Any questions or queries about open science can be directed to: openscience@ucl.ac.uk.

Get involved!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

The Predatory Paradox – book review

By Kirsty, on 29 February 2024

Guest post from Huw Morris, Honorary Professor of Tertiary Education, UCL Institute of Education. If anyone would like to contribute to future blogs, please get in touch.

Review of The Predatory Paradox: Ethics, Politics and the Practices in Contemporary Scholarly Publishing (2023). Amy Koerber, Jesse Starkey, Karin Ardon-Dryer, Glenn Cummins, Lyombe Eko and Kerk Kee. Open Book Publishers. DOI 10.11647/obp.0364.

Review of The Predatory Paradox: Ethics, Politics and the Practices in Contemporary Scholarly Publishing (2023). Amy Koerber, Jesse Starkey, Karin Ardon-Dryer, Glenn Cummins, Lyombe Eko and Kerk Kee. Open Book Publishers. DOI 10.11647/obp.0364.

We are living in a publishing revolution, in which the full consequences of changes to the ways research and other scholarly work are prepared, reviewed and disseminated have yet to be fully felt or understood. It is just over thirty years since the first open access journals began to appear on email groups in html and pdf formats.

It is difficult to obtain up-to-date and verifiable estimates of the number of journals published globally. There are no recent journal articles which assess the scale of this activity. However, recent online blog sources suggest that there are at least 47,000 journals available worldwide of which 20,318 are provided in open access format (DOAJ, 2023; WordsRated, 2023). The number of journals is increasing at approximately 5% per annum and the UK provides an editorial home for the largest proportion of these titles.

With this rapid expansion questions have been raised about whether there are too many journals, whether they will continue to exist in their current form, and if so how can readers and researchers assess the quality of the editorial processes they have adopted (Brembs et al., 2023; Oosterhaven, 2015)

This new book, ‘The Predatory Paradox,’ steps into these currents of change and seeks not only to comment on developments, but also to consider what the trends mean for academics, particularly early career researchers, for journal editors and for the wider academic community. The result is an impressive collection of chapters which summarise recent debates and report the authors’ own research examining the impact of these changes on the views of researchers and crucially their reading and publishing habits.

The book is divided into seven chapters, which consider the ethical and legal issues associated with open access publishing, as well as the consequences for assessing the quality of articles and journals. A key theme in the book, as the title indicates, is tracking the development of concern about predatory publishing. Here the book mixes a commentary on the history of this phenomenon with information gained from interviews and the authors’ reflections on the impact of editorial practices on their own publication plans. In these accounts the authors demonstrate that it is difficult to tightly define what constitutes a predatory journal because peer review and editorial processes are not infallible, even at the most prestigious journals. These challenges are illustrated by the retelling of stories about recent scientific hoaxes played on so-called predatory journals and other more respected titles. These hoaxes include the submission of articles with a mix of poor research designs, bogus data, weak analyses and spurious conclusions. Building on insights derived from this analysis, the book’s authors provide practical guidance about how to avoid being lured into publishing in predatory journals and how to avoid editorial practices that lack integrity. They also survey the teaching materials used to deal with these issues in the training of researchers at the most research-intensive US universities.

One of the many excellent features of the book is its authors practicing much of what they preach. The book is available for free via open access in a variety of formats. The chapters which draw on original research provide links to the underpinning data and analysis. At the end of each chapter there is also a very helpful summary of the key takeaway messages, as well as a variety of questions and activities that can be used to prompt reflection on the text or as the basis for seminar and tutorial activities.

Having praised the book for its many fine features, it is important to note the questions it raises about defining quality research which could have been more fully answered. The authors summarise their views about what constitutes quality research under a series of headings drawing on evidence from interviews with researchers in a range of subject areas they conclude that quality research defies explicit definition. They suggest, following Harvey and Green, that it is multi-factorial and changes over time with the identity of the reviewer and reader. This uncertainty, while partially accurate, has not prevented people from rating the quality of other peoples’ research or limited the number of people putting themselves forward for these types of review.

As the book explains, peer review by colleagues with an expertise in the same specialism, discipline or field is an integral part of the academic endeavour. Frequently there are explicit criteria against which judgements are made, whether for grant awards, journal reviewing or research assessment. The criteria may be unclear, open to interpretation, overly narrow or overly wide, but they do exist and have been arrived at through collective review and confirmed by processes involving many reviewers.

Overall I would strongly recommend this book and suggest that it should be required or background reading on research methods courses for doctoral and research masters programmes. For other readers who are not using this book as part of a course of study, I would recommend also reading research assessment guidelines for research council and funding body websites and advice to authors provided by long established journals in their field. In addition, it is worth looking at the definitions and reports on research activity provided by Research Excellence Framework panels in the UK and their counterparts in other nations.

Get involved!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, LinkedIn, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, LinkedIn, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

Getting a Handle on Third-Party Datasets: Researcher Needs and Challenges

By Rafael, on 16 February 2024

Guest post by Michelle Harricharan, Senior Research Data Steward, in celebration of International Love Data Week 2024.

ARC Data Stewards have completed the first phase of work on the third-party datasets project, aiming to help researchers better access and manage data provided to UCL by external organisations.

The problem:

Modern research often requires access to large volumes of data generated outside of universities. These datasets, provided to UCL by third parties, are typically generated during routine service delivery or other activities and are used in research to identify patterns and make predictions. UCL research and teaching increasingly rely on access to these datasets to achieve their objectives, ranging from NHS data to large-scale commercial datasets such as those provided by ‘X’ (formerly known as Twitter).

Currently, there is no centrally supported process for research groups seeking to access third-party datasets. Researchers sometimes use departmental procedures to acquire personal or university-wide licenses for third-party datasets. They then transfer, store, document, extract, and undertake actions to minimize information risk before using the data for various analyses. The process to obtain third-party data involves significant overhead, including contracts, compliance (IG), and finance. Delays in acquiring access to data can be a significant barrier to research. Some UCL research teams also provide additional support services such as sharing, managing access to, licensing, and redistributing specialist third-party datasets for other research teams. These teams increasingly take on governance and training responsibilities for these specialist datasets. Concurrently, the e-resources team in the library negotiates access to third-party datasets for UCL staff and students following established library procedures.

It has long been recognized that UCL’s processes for acquiring and managing third-party data are uncoordinated and inefficient, leading to inadvertent duplication, unnecessary expense, and underutilisation of datasets that could support transformative research across multiple projects or research groups. This was recognised in the “Data First, 2019 UCL Research Data Strategy”.

What we did:

Last year, the ARC Data Stewards team reached out to UCL professional services staff and researchers to understand the processes and challenges they faced regarding accessing and using third-party research datasets. We hoped that insights from these conversations could be used to develop more streamlined support and services for researchers and make it easier for them to find and use data already provided to UCL by third parties (where this is within licensing conditions).

During this phase of work, we spoke with 14 members of staff:

- 7 research teams that manage third-party datasets

- 7 members of professional services that support or may support the process, including contracts, data protection, legal, Information Services Division (databases), information security, research ethics and integrity, and the library.

What we’ve learned:

An important aspect of this work involved capturing the existing processes researchers use when accessing, managing, storing, sharing, and deleting third-party research data at UCL. This enabled us to understand the range of processes involved in handling this type of data and identify the various stakeholders involved—or who potentially need to be involved. In practice, we found that researchers follow similar processes to access and manage third-party research data, depending on the security of the dataset. However, as there is no central, agreed procedure to support the management of third-party datasets in the organization, different parts of the process may be implemented differently by different teams using the methods and resources available to them. We turned the challenges researchers identified in accessing and managing this type of data into requirements for a suite of services to support the delivery and management of third-party datasets at UCL.

Next steps:

We have been working on addressing some of the common challenges researchers identified. Researchers noted that getting contracts agreed and signed off takes too long, so we reached out to the RIS Contract Services Team, who are actively working to build additional capacity into the service as part of a wider transformation programme.

Also, information about accessing and managing third-party datasets is fragmented, and researchers often don’t know where to go for help, particularly for governance and technical advice. To counter this, we are bringing relevant professional services together to agree on a process for supporting access to third-party datasets.

Finally, respondents noted that there is too much duplication of data. The costs for data are high, and it’s not easy to know what’s already available internally to reuse. In response, we are building a searchable catalogue of third-party datasets already licensed to UCL researchers and available for others to request access to reuse.

Our progress will be reported to the Research Data Working Group, which acts as a central point of contact and a forum for discussion on aspects of research data support at UCL. The group advocates for continual improvement of research data governance.

If you would like to know more about any of these strands of work, please do not hesitate to reach out (email: researchdata-support@ucl.ac.uk). We are keen to work with researchers and other professional services to solve these shared challenges and accelerate research and collaboration using third-party datasets.

Get involved!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

FAIR Data in Practice

By Rafael, on 15 February 2024

Guest post by Victor Olago, Senior Research Data Steward and Shipra Suman, Research Data Steward, in celebration of International Love Data Week 2024.

The problem:

We all know sharing is caring, and so data needs to be shared to explore its full potential and usefulness. This makes it possible for researchers to answer questions that were not the primary research objective of the initial study. The shared data also allows other researchers to replicate the findings underpinning the manuscript, which is important in knowledge sharing. It also allows other researchers to integrate these datasets with other existing datasets, either already collected or which will be collected in the future.

There are several factors that can hamper research data sharing. These might include a lack of technical skill, inadequate funding, an absence of data sharing agreements, or ethical barriers. As Data Stewards we support appropriate ways of collecting, standardizing, using, sharing, and archiving research data. We are also responsible for advocating best practices and policies on data. One of such best practices and policies includes the promotion and the implementation of the FAIR data principles.

FAIR is an acronym for Findable, Accessible Interoperable and Reusable [1]. FAIR is about making data discoverable to other researchers, but it does not translate exactly to Open Data. Some data can only be shared with others once security considerations have been addressed. For researchers to use the data, a concept-note or protocol must be in place to help gatekeepers of that data understand what each data request is meant for, how the data will be processed and expected outcomes of the study or sub study. Findability and Accessibility is ensured through metadata and enforcing the use of persistent identifiers for a given dataset. Interoperability relates to applying standards and encoding such as ICD-10, ICDO-3 [2] and, lastly, Reusability means making it possible for the data to be used by other researchers.

What we are doing:

We are currently supporting a data reuse project at the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit (MRC CTU). This project enables the secondary analysis of clinical trial data. We use pseudonymisation techniques and prepare metadata that goes along with each data set.

Pseudonymisation helps process personal data in such a way that the data cannot be attributed to specific data subjects without the use of additional information [3]. This reduces the risks of reidentification of personal data. When data is pseudonymized direct identifiers are dropped while potentially identifiable information is coded. Data may also be aggregated. For example, age is transformed to age groups. There are instances where data is sampled from the original distribution, allowing only sharing of the sample data. Pseudonymised data is still personal data which must be protected with GDPR regulation [4].

The metadata makes it possible for other researchers to locate and request access to reuse clinical trials data at MRC CTU. With the extensive documentation that is attached, when access is approved, reanalysis and or integration with other datasets are made possible. Pseudonymisation and metadata preparation helps in promoting FAIR data.

We have so far prepared one data-pack for RT01 studies which is ‘A randomized controlled trial of high dose versus standard dose conformal radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer’ which is currently in review phase and almost ready to share with requestors. Over the next few years, we hope to repeat and standardise the process for past, current and future studies of Cancer, HIV, and other trials.

References:

- 8 Pillars of Open Science.

- Digital N: National Clinical Coding Standards ICD-10 5th Edition (2022), 5 edn; 2022.

- Anonymisation and Pseudonymisation.

- Complete guide to GDPR compliance.

Get involved!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

Finding Data Management Tools for Your Research Discipline

By Rafael, on 14 February 2024

Guest post by Iona Preston, Research Data Support Officer, in celebration of International Love Data Week 2024.

While there are a lot of general resources to support good research data management practices – for example UCL’s Research Data Management webpages – you might sometimes be looking for something a bit more specific. It’s good practice to store your data in a research data repository that is subject specific, where other people in your research discipline are most likely to search for data. However, you might not know where to begin your search. You could be looking for discipline-specific metadata standards, so your data is more easily reusable by academic colleagues in your subject area. This is where subject-specific research data management resources become valuable. Here are some resources for specific subject areas and disciplines that you might find useful:

- The Research Data Management Toolkit for Life Sciences

This resource guides you through the entire process of managing research data, explaining which tools to use at each stage of the research data lifecycle. It includes sections on specific life science research areas, from plant sciences to rare disease data. These sections also cover research community-specific repositories and examples of metadata standards. - Visual arts data skills for researchers: Toolkits

This consists of two different tutorials covering an introduction to research data management in the visual arts and how to create an appropriate data management plan. - Consortium of European Social Science Data Archives

CESSDA brings together data archives from across Europe in a searchable catalogue. Their website includes various resources for social scientists to learn more about data management and sharing, along with an extensive training section and a Data Management Expert Guide to lead you through the data management process. - Research Data Alliance for Disciplines (various subject areas)

The Research Data Alliance is an international initiative to promote data sharing. They have a webpage with special interest groups in various academic research areas, including agriculture, biomedical sciences, chemistry, digital humanities, social science, and librarianship, with useful resource lists for each discipline. - RDA Metadata Standards Catalogue (all subject areas)

This directory helps you find a suitable metadata scheme to describe your data, organized by subject area, featuring specific schemes across a wide range of academic disciplines. - Re3Data (all subject areas)

When it comes to sharing data, we always recommend you check if there’s a subject specific repository first, as that’s the best place to share. If you don’t know where to start finding one, this is a great place to look with a convenient browse feature to explore available options within your discipline.

These are only some of the different discipline specific tools that are available. You can find more for your discipline on the Research Data Management webpages. If you need any help and advice on finding data management resources, please get in touch with the Research Data Management team on lib-researchsupport@ucl.ac.uk.

Get involved!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

Research Data Stewardship at UCL

By Rafael, on 13 February 2024

Guest post by James A J Wilson, Head of Research Data in Advance Research Computing at UCL, in celebration of International Love Data Week 2024.

A Research Data Steward is a relatively recent term for someone undertaking a range of jobs that have already been undertaken for some time, albeit sometimes without due appreciation. If you have helped researchers manage their data – helping with data management plans, adding metadata, providing services for data hosting, preparing datasets for analysis, scripting data transformations, readying data for sharing or publication, or engaging in long-term data preservation and curation – you may have unwittingly been a data steward.

As the importance of data for enabling research reproducibility and transparency becomes more widely recognized, so does the importance of good data stewardship. In 2016, the European Commission’s publication ‘Realising the European Open Science Cloud’, estimated that, “on average, about 5% of research expenditure should be spent on properly managing and stewarding data”[1]. Whilst the world and UCL are not at that level yet, the importance of managing research data more effectively has not passed the university by.

Advanced Research Computing (ARC) has established four different Research Technology professions. Besides our Research Software Engineers (who already have more than a decade of experience behind them at UCL) there are now groups of Research Infrastructure Developers, Data Scientists, and Data Stewards. None of the roles that the teams take on are new, but there are advantages to treating the people who make up those professions as members of a profession, rather than assorted and frequently rather isolated postdocs. Firstly, we now have a pool of people who can exchange experiences, impart knowledge to one another, and lend each other a bit of moral support. Secondly, it enables the development of focused career paths. No longer do research technology professionals need to kick their heels working on barely recognized tasks until they get an opportunity to break into the research big time. Their importance is recognized and can be rewarded.

There are now more than a dozen professional research data stewards in ARC. Team members develop and support services, collaborate with research teams from other departments to ensure that their data is as well managed and as FAIR as possible (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), and undertake research themselves. Examples of research projects include work with eChild; preparing data packs for the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit (MRC CTU); supplying the MAESaM and CAAL archaeology projects with geospatial data and mapping software expertise and helping to prepare bids across a range of disciplines. Some projects are more infrastructure based, such as the EU-funded DICE project to establish services for data processing pipelines. Other work is focused on improving UCL’s services and their coordination, such as the ‘3rd-party data’ project, which seeks to help researchers obtain data from other organisations and enable broader awareness of and access to that data. We’re also working with departments, helping them migrate data to centrally managed storage.

The ARC Research Data Stewards are not the only people engaged in data stewardship at UCL. Many people across different projects and teams are involved in aspects of data stewardship. Most obviously, our close colleagues in UCL Library’s Research Data Management team, but also those working on services to provide particular datasets or metadata, plus all those on research contracts working away at polishing and processing data in labs, libraries, and offices across Bloomsbury and beyond. We will shortly begin forming a Data Stewardship Community of Practice, to create a forum where everyone involved in this important work can exchange ideas and start to form a sense of what really constitutes ‘best practice’.

If you are based at UCL and are potentially interested in working with us, drop us a line at researchdata-support@ucl.ac.uk.

Get involved!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

[1] European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Realising the European open science cloud – First report and recommendations of the Commission high level expert group on the European open science cloud, Publications Office, 2016, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/940154

Research Data Management: A year in review

By Rafael, on 12 February 2024

Guest post by Dr Christiana McMahon, Research Data Support Officer, in celebration of International Love Data Week 2024.

From that spark of an idea through to publishing research findings, the Research Data Management team have once again been on-hand to support staff and students.

What’s been happening?

A new version of the Research Data Repository is now available simplifying the process of archiving and preserving research outputs here at UCL for the longer-term.

In 2023 we published 200 items 151 of which were datasets.

Over the past year…

Over the past year…

- The most downloaded record was: Griffiths, David; Boehm, Jan (2019). SynthCity Dataset – Area 1. University College London. Dataset.

- The most viewed record was: Heenan, Thomas; Jnawali, Anmol; Kok, Matt; Tranter, Thomas; Tan, Chun; Dimitrijevic, Alexander; et al. (2020). Lithium-ion Battery INR18650 MJ1 Data: 400 Electrochemical Cycles (EIL-015). University College London. Dataset.

- The most cited record was: Manescu, Petru; Shaw, Mike; Elmi, Muna; Zajiczek, Lydia; Claveau, Remy; Pawar, Vijay; et al. (2020). Giemsa Stained Thick Blood Films for Clinical Microscopy Malaria Diagnosis with Deep Neural Networks Dataset. University College London. Dataset.

More information is available about the UCL Research Data Repository. Alternatively, check our FAQs.

Data Management Plan Reviews

The RDM team can review data management plans providing researchers with feedback in-line with UCL’s expectations and funding agency requirements where these apply. In 2023, we reviewed 32 data management plans covering over 10 different funding agencies. More information is available in our website.

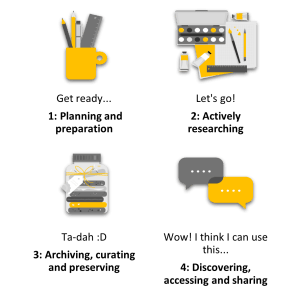

Mini-tutorial: Research data lifecycle

The RDM team often refer to the research data lifecycle, but what is it? Essentially, these are the different stages of the research process from planning and preparation through to archiving your research outputs, making them discoverable to the wider research community and members of the public.

The four stages:

1: Get ready – You’ve had an idea for a research study so it’s time to start making plans and getting prepared. Have you considered writing a data management plan?

- Remember, if you are in receipt of external funding, there may be data management requirements to consider.

- Feel free to reach out to Open Science and Research Support to assist you.

2: Let’s go – You are now actively researching putting all those research plans into action.

- Don’t forget to revisit your data management plan and update it to reflect your latest decision making.

- It’s also useful to consider documenting your research as you progress.

3: Ta-dah – The research is complete and it’s time to archive your research outputs to preserve them for the longer-term.

- Aim to utilise subject-specific archives and repositories where possible.

- Creating a metadata record in a public facing online catalogue with links to any related publications can be useful to building online networks of linked research outputs.

- Consider making your research outputs as openly accessible as possible remembering that controlling or restricting access is fine as long as it is justified and there is a set data access protocol in place to facilitate a data access request.

- Did you know you can archive most research outputs in the UCL Research Data Repository?

4: Wow! I think I can use this – making your research discoverable to others for potential reuse can help to maximise research opportunities

- Consider having an agreement in place between parties before sharing research outputs – issues like copyright, IP, commercialisation of (subsequent) work may be discussed here.

- For secondary researchers, time to head back to the start to begin the research process.

And so the research data lifecycle begins again!

Get involved!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

The UCL Office for Open Science and Scholarship invites you to contribute to the open science and scholarship movement. Stay connected for updates, events, and opportunities. Follow us on X, formerly Twitter, and join our mailing list to be part of the conversation!

Close

Close

!["We invite you to share your insights on the UCL Research Repository and help us improve our service! Take just 5-10 mins to complete a brief internal survey. Thank you! [Link: https://buff.ly/3Tg1Fna] Image: A figure with blue & green clothing with a speech bubble reading 'tell us what you think'.](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/open-access/files/2024/04/Copy-of-Pink-Minimal-Recruitment-Twitter-Post-1-5d3ce82295fad533-300x169.png)