The Nahrein Network’s recent trip to Iraq

By Zainab, on 20 March 2024

On our first port of call in Iraq was Kirkuk, where the Nahrein Network’s Professor Eleanor Robson and Dr Mehiyar Kathem had the opportunity to visit its provincial capital. The Nahrein Network met with Dr Mustafa Muhsin (Kirkuk University) and Dr Khalil al Jabouri (Tikrit University) to discuss their project on cultural heritage and minorities in the province. Dr Mustafa Muhsin and Dr Dlshad Oumar (also a historian at the University of Kirkuk and a previous Nahrein Network – British Institute for the Study of Iraq Visiting Scholar) arranged a superb seminar on the work of the Nahrein Network.

Professor Eleanor Robson at University of Kirkuk speaking with colleagues in the History Department

We were warmly welcomed by the Dean of the College of Arts, Dr Omar al Deen, who also participated in the workshop at the university.

A scientific event and symposium held by the Dept of History @UOKIRKUKHISTOR1 at the College of Arts,Univer of Kirkuk,in which the Director @Eleanor_Robson of @NahreinNetwork participated and was attended by the Deputy @Mehiyar and the staff as well as students of college ⤵️⤵️ pic.twitter.com/IMYK4Kvww9

— Dr mustafa mehsen (@DrMustafa112016) February 12, 2024

The team also had the pleasure of meeting the president of the University of Kirkuk, Dr Omran Hussein, where Professor Eleanor Robson spoke about the rich history of Kirkuk and its significance to Iraq.

In addition, the team led by Dr Mustafa Muhsin organised a meeting with Dr. Yousif Thomas Mirkis, Archbishop of the Chaldean Archeparchy of Kirkuk and Sulimaniyah, who welcomed the Nahrein Network supported project on Kirkuk’s minorities and proposed to host several of its workshops and other activities.

London team visits the historic Kirkuk Citadel

A visit to Kirkuk citadel and the Shrine of Prophet Daniel was also a highlight of the trip to Kirkuk.

Another major highlight of our trip, this time in Baghdad, was a joint workshop organised with five teams who are working on different cultural heritage related projects in Iraq. Discussions ensued, good lessons were exchanged and the project teams were able to network with each other.

On this trip to Baghdad, Professor Eleanor Robson and Dr Mehiyar Kathem had the pleasure of meeting Dr Naeem Abed Yasir, the Minister of Higher Education and Scientific Research. The Nahrein Network’s current activities and plans for future collaboration were discussed as well as how to strengthen UK – Iraq higher education knowledge-based partnerships and exchange.

Prof Eleanor and Dr Mehiyar with the Minister of Higher Education and Scientific Research

The Nahrein Network team also met with Dr Bahaa Ansaf, President of the University of Baghdad, where ideas for research collaborations were discussed, including initiatives led by the university for the rehabilitation of their natural history museum as well as strengthening museum skills development.

Professor Eleanor Robson and Dr Mehiyar Kathem with Professor Bahaa Ansaf, President of the University of Baghdad

The team then visited the archaeological site of Babylon, accompanied by Ammar al Taee (archaeologist at the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage) and Dr Haider al Mamori (archaeologist and academic at the University of Babylon). Dr Ali Naji from the University of Kufa also accompanied the Nahrein Network team on a tour of the ancient city.

UNESCO listed World Heritage Site of Babylon

From Babil, the Nahrein Network team then visited historic Kufa, in the province of Najaf, where Dr Ali Naji is implementing a project exploring the historic buildings of the city.

After Najaf, the Nahrein Network visited the marshes in al Chibayish, in the province of DhiQar, accompanied by our colleague Dr Hamid Samir (Head of Architecture at the University of Basrah).

Dr Hamid Samir of Basra University with Eleanor Robson in Chibayish

The Nahrein Network also had the pleasure of meeting with the President of the University of Basrah where Dr Hamid Samir’s project on climate change and its impact on heritage buildings in Basrah (in collaboration with Loughborough University in the United Kingdom) was discussed. Later, in the presence of Dr Hamid Samir, a discussion took place with his undergraduate students at the university.

This trip ended with a visit to Al Ashar canal and its rich cultural heritage, an area that was recently worked on for rehabilitation by UNECO and the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage.

Mustafa al Hussainy, Head of Basrah’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage also accompanied the Nahrein Network team on a short walk to visit some of the 11 heritage buildings that had recently been worked on for rehabilitation.

The low groundwater level in Babylon

By Zainab, on 20 February 2024

BY AMMAR AL-TAEE

Babylon, especially as the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626-539 BC), is significant for its historical and cultural accomplishments but it also was a place where early technologies sought to address water management through incomparable feats of engineering. The Shatt al-Hillah, one of the branches of the Euphrates River, passes through the center of Babylon, dividing it into eastern and western parts. That relationship served well in trade, transport, defending the city, and irrigating its fields, but it also posed complicated challenges to maintain the city. Groundwater, tied to the level of the Shatt al-Hillah, continued to confound the Babylonians throughout the city’s history. Likewise, it posed challenges to modern archaeological excavations. First, the German presence at the turn of the last century, and later Iraqi expeditions, struggled to go deeper into the city’s archaeological layers; as soon as they were excavated, pits filled with water, preventing archaeologists from knowing more about the early periods, including those of Hammurabi.

Water shortages in the Shatt al-Hillah occurred in the second half of the 19th Century because the intensity of discharge of the Euphrates caused scouring of the river bed downstream of the Shatt al-Hillah branch. Hence, water movement increased toward the main branch of the Euphrates with fewer discharges into the Shatt al-Hillah; sediments began to accumulate in the Shatt al-Hillah branch causing the river bed to rise. Ottoman Authorities took measures in the last quarter of the 19th Century when a French engineer named Schoenderfer was entrusted to find a solution. A weir across the Euphrates River was built, but it could not withstand the currents.

After the British engineer Willcock’s intervention, a barrage known as the Hindiyah Dam was completed and opened in 1913, and as Shatt al-Hillah water levels began to rise again, so did groundwater levels in Babylon. Between the initial weir and barrage, there was a golden opportunity for the Robert Koldewey expedition to excavate Babylon. Olof Pedersen mentions in his book Babylon the Great City that in between the constructions, the groundwater dropped to −3.55 meters (= 21.95 MASL, meters above sea level), allowing Koldewey’s team to excavate down to levels now impossible to reach. As a result, the first excavations of Old Babylonian and Middle Babylonian levels took place at higher parts of the city, especially at private houses in the Merkes area.

Figure 1, North wall of the Palace after the groundwater level decreased, November 1911, Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft

After the barrage was built at Sadat al-Hindiyya, the groundwater levels at Babylon became one of the biggest problems facing the process of developing the ancient city for tourism. In the late years of royal rule, the Iraqi monarchy sent experts, headed by young archaeologists Taha Baqir and Fouad Safar, to ascertain ways to develop Babylon’s visitor infrastructure and find appropriate solutions to the issues of groundwater levels. The responsible team set to work, but alas, the monarchy soon collapsed in 1958 with a military coup led by Abdul Karim Qasim and the project was halted.

Later, referring to the King’s initial idea, Saddam Hussein launched a project called the ‘Revival of Babylon’ and instructed Iraqi archaeologists and engineering teams to start planning tourism development. The first initiative, coming out of a 1979 international conference, addressed the issue of groundwater under Babylon. However, the revival of the country’s heritage and archaeological resources was hijacked by Hussein’s political ambitions steeped in a personal agenda, which cost Babylon an important and essential part of its heritage.

With the beginnings of the Iraq-Iran war in full swing and accompanying signs of political unrest in the country, Saddam Hussein sought to enhance his personal glory by twisting the Babylon project, and instead of working to address the high levels of groundwater, he dug water canals with four artificial lakes, surrounding the central part of Babylon with water on all sides, and the groundwater problem increased. Between the 1960s and 1980s, the effect was caustic on Babylon’s exposed archaeology. The increased moisture brought salts with it, and capillary action devastated the original masonry walls just above ground level; Ishtar Gate’s famed animals, the mušhuššu-dragons and the bulls, began dissolving into dust.

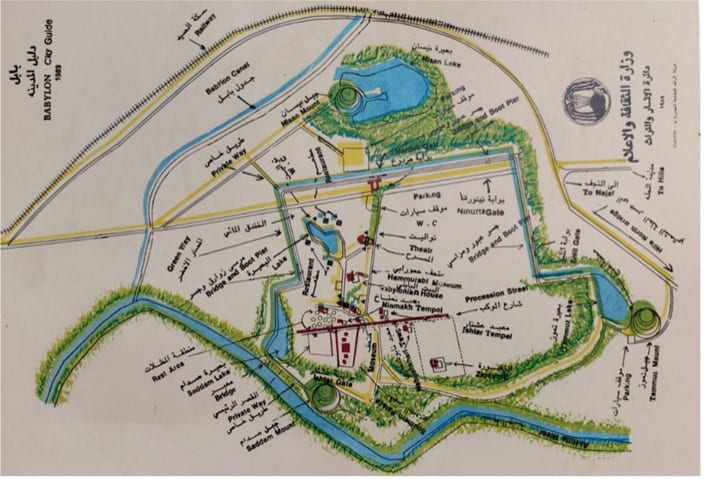

Figure 2, Map of Babylon after completing Babylon Revival Project and filling the lakes with water, 1989, credit: SBAH

Several cosmetic remedies tried to hide the problem by treating Ishtar Gate’s degrading masonry symptoms rather than solving the root cause. Rather than replace crumbling ancient Babylon’s mud and bitumen mortars and respect Neo-Babylonian brick types, the Ishtar Gate was subjected to heavy-handed and inappropriate cement mortars and wrongly selected brick masonry infills. Instead of matching the Neo-Babylonian masonry, a patchwork installation featuring modern construction bricks normally used in houses was installed. To add insult to injury, at the Ishtar Gate, a heavy concrete floor was poured inside, blocking moisture evaporation. With no place to go, trapped humidity migrated deep into the masonry. These interventions only accelerated the erosion of the lower parts of the monument.

After the downfall of Hussein, removing the cast concrete floor became a priority. World Monument Fund (WMF) and the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH), pulled it up and explored the depth of the Ishtar Gate. They were not able to reach Koldewey’s levels, as Babylon had become, so to speak, a floating city on a lake of groundwater sitting mere centimeters below.

Later, in the summer of 2016-2017, the WMF and SBAH made another section on the western side of the Ishtar Gate, hoping that groundwater levels in the summer would be low, but they discovered underground water 150 cm below the floor, and an intact mušhuššu relief swimming up to its neck in groundwater.

Figure 3, The Mushkhushu is swimming in the water 150 cm below the ground, 2016, credit: WMF

In July 2023, WMF and SBAH began large-scale replacement of Ishtar Gate’s inappropriate modern infill bricks and their cement-based mortar. Excavations along the masonry facades meant to find the depth of these modern replacements to calculate costs for substituting in more sympathetic brickwork. Surprisingly, in some locations, the replacement continued 250 cm to 300 cm below the former concrete floor level, and the groundwater level was now below that. The mystery of why the infills were so deep was found in the SBAH’s archive. Only one paper mentioning that in 1958, a team from the SBAH, headed by Salem al-Alusi, with Kadhim al-Janabi and Najib Kiso, removed the dragons and bulls from the lower eastern side of the Ishtar Gate for the purpose of maintenance in the SBAH laboratories. But that created another question: why were the reliefs not returned to their places after their maintenance and why were they not in SBAH’s stores? So where did they go?

A piece of the riddle happened in 2019. Wahbi Abdel Razzaq, a retired SBAH archaeologist, who had an important role in the project to revive of Babylon, told me, “The SBAH removed parts of the masonry from below and reinstalled the dragons and bulls, on top of the Ishtar Gate.” Mr. Wahbi did not explain to me the details, which seemed strange to me at that time.But the historic photos of Babylon explain to us the process clearly and provide the final clue to understanding what happened. Photos taken in the 1950s show that the level of the excavated intact parts of the Ishtar Gate found by the Koldewey, and later Iraqi missions, show it was not that high, but rather lower. Mr. Wahbi’s words were correct. That is, in reflection of the masonry damage suffered on the west side, the lower parts being affected by rising damp on the east side were raised to be at the top of the Ishtar Gate.

Figure 4, before the animals were moved to the top of Ishtar gate from the bottom, 1950s, credit: SBAH

Figure 5, after the animals were moved to the top of the gate from the bottom, 2023, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

The strange thing is that despite our descent to more than three meters underground, the groundwater did not emerge before reaching 26.3 MASL! Which indicates a significant decrease in groundwater levels in Babylon compared to the year 2016. This is positive for those wishing to carry out archaeological excavations within the site of Babylon. On the other hand, this matter is a serious indicator that the groundwater levels in Babylon, which is in the middle of Iraq are witnessing a widespread and accelerating decline.

Figure 6, during the excavation process, 2023, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

Recently, the Water Resources Department provided me with the water levels of the Shatt al-Hillah, during the past seven years. The water level had decreased by about 2 m from 28 MASL in 2020 to 26 MASL in 2023. The result is a decline in groundwater levels in Babylon because the groundwater is mostly fed by the river. Especially after many of the neighboring upstream countries took an offensive stance to ensure that their people get enough water at the expense of Iraq’s water shares, ignoring international treaties related to the regulation and use of water.

As the Shatt al-Hillah continues to shrink, groundwater has become a major source of water for farmers after river water levels decreased or dried up. This was confirmed by Omran Nahr, who lives in one of the villages adjacent to Babylon and works in drilling wells. Nahr says, “During the last seven years, my business started to boom, to the point that I abandoned the manual method of digging wells and bought a machine for digging wells.” According to Nahr’s opinion, the groundwater level in the villages surrounding Babylon was reduced by about 3-4 m. As for southern Babylon, especially in the villages surrounding Borsippa around 20 km to the south of Babylon, it decreased by 8 m. “I used to dig 10 m to reach groundwater, but now I need to dig around 18 m”.

This is an indication of the beginning of the depletion of groundwater, which represents a major economic and environmental threat, especially in light of the major climate change crisis that is afflicting Iraq, in turn, will lead to a decline in crop yields, and it is expected that the current trend represented in Iraq will continue. Hotter, drier, and a large water deficit for decades, which will reduce the country’s domestic food supply and turn the land into salt fields.

Figure 7, the land turned into salt, the area south of Ninurta temple in 2023, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

Intangible Heritage of Najaf

By Zainab, on 24 January 2024

We talk to Dr Ali Naji Attiyah, Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Engineering, University of Kufa. Dr Ali Naji Attiyah held a Nahrein – BISI Visiting Scholarship at Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL. Dr Ali Naji Attiyah’s project is titled Intangible Heritage of Najaf and is under the supervision of Professor Edward Denison.

Tell us a little about yourself.

Dr Ali Naji with Prof Eleanor Robson at UCL

My name is Dr. Ali Naji Attiyah, I am an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Engineering in University of Kufa. I got a Ph.D. in Structural Engineering from University of Baghdad. My interest in cultural heritage started in 2003 when I worked as a consultant on the conservation of the Imam Ali shrine in Najaf City. I wrote a book titled the “Spiritual Values of the Holy Shrines Architecture”. I tried to explore the intangible values affected the traditional design of the shrines. I was appointed to be a member of the National Committee to inscribe Wadi Al-Salam Cemetery to the World Heritage List. For this I got training courses at the UNESCO Iraq Office on the protection and enhancement of tangible and intangible heritage. In 2019, I earned a grant of 30,000 GBP from Nahrein Network to document the heritage buildings in Kufa City.

Tell us more about your project.

The project aims to explore the interrelation between tangible and intangible cultural heritage to increase the awareness of people to cultural heritage. The proposed project briefly discusses the idea of the correlation between spirit and matter from the fact of that the strength of urban output is the product of its moral dimension. The historic centre of Najaf with its society and culture represents the treasure of knowledge and culture, a centre for science and human development. Hence, there is a need to keep all these values through revival of the historic part of the city. An approach will be presented and discussed with experts in UK to revive Najaf tangible cultural heritage in the historic centre of the city. The approach will depend on defining the intangible cultural heritage elements related to the buildings and old city fabric, which will arise the values imbedded inside the tangible heritage. Such values will increase the awareness of communities belong to Najaf to the importance of its cultural heritage.

What was the highlight of your trip?

A seminar was organized by Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa EAMENA, which was based at the University of Oxford. I described the role of intangible cultural heritage in the revival of tangible heritage and he considered the historic City of Najaf as a case study, where the presentation title was: “Najaf, Iraq: Developing a Sustainable Approach to Threatened Heritage”.

The Nahrein Network – UCL and the British Institute for the Study of Iraq organized a symposium on the “Future of Najaf Cultural Heritage, A View on Sustainable Approach”. The seminar was a good opportunity to make use of the experience of visiting many British heritage cities such as Oxford and York. The comparison focused on the challenges faced by their heritage and are continued, because of the needs and development projects. However, the regulations written for the York City Council in the 1990s were briefly reviewed as they may be a good resource for the recently established Najaf Historic Center municipality.

The visit to the Cities of Oxford and York was very useful, as those cities keep their urban and architectural identity. The university buildings at Oxford were deep-rooted and survived for a hundred years and are attractive for visits of tourists. So, they are good examples of living heritage buildings, their academic function still works in the same traditions. Najaf’s old schools have the same cultural identity and can be attractive for tourism, where thousands of scientists lived and studied. The City of York’s heritage faced a lot of challenges since the late 1960s, when the need for development projects increased rapidly. Many similarities and differences as well can be seen between York and Najaf. For example, both cities receive millions of visitors annually and this issue adds pressure on their cultural heritage. The main difference can be seen in the living heritage, where this type of heritage has been practiced in Najaf for a hundred years and is threatened by the potential changes in the city buildings and alleys. But in the case of York, the main challenge is the archeological sites under the city, where the ruins of Romans and Vikings are the base of the buildings built later.

What was the highlight of your trip?

A seminar was organized by Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa EAMENA, which was based at the University of Oxford. I described the role of intangible cultural heritage in the revival of tangible heritage and he considered the historic City of Najaf as a case study, where the presentation title was: “Najaf, Iraq: Developing a Sustainable Approach to Threatened Heritage”.

A seminar was organized by Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa EAMENA, which was based at the University of Oxford. I described the role of intangible cultural heritage in the revival of tangible heritage and he considered the historic City of Najaf as a case study, where the presentation title was: “Najaf, Iraq: Developing a Sustainable Approach to Threatened Heritage”.

The Nahrein Network – UCL and the British Institute for the Study of Iraq organized a symposium on the “Future of Najaf Cultural Heritage, A View on Sustainable Approach”. The seminar was a good opportunity to make use of the experience of visiting many British heritage cities such as Oxford and York. The comparison focused on the challenges faced by their heritage and are continued, because of the needs and development projects. However, the regulations written for the York City Council in the 1990s were briefly reviewed as they may be a good resource for the recently established Najaf Historic Center municipality.

The visit to the Cities of Oxford and York was very useful, as those cities keep their urban and architectural identity. The university buildings at Oxford were deep-rooted and survived for a hundred years and are attractive for visits of tourists. So, they are good examples of living heritage buildings, their academic function still works in the same traditions. Najaf’s old schools have the same cultural identity and can be attractive for tourism, where thousands of scientists lived and studied. The City of York’s heritage faced a lot of challenges since the late 1960s, when the need for development projects increased rapidly. Many similarities and differences as well can be seen between York and Najaf. For example, both cities receive millions of visitors annually and this issue adds pressure on their cultural heritage. The main difference can be seen in the living heritage, where this type of heritage has been practiced in Najaf for a hundred years and is threatened by the potential changes in the city buildings and alleys. But in the case of York, the main challenge is the archeological sites under the city, where the ruins of Romans and Vikings are the base of the buildings built later.

Did you have any promising conversations or collaborations with colleagues at UCL or other institutions?

The first activity was the meeting with Dr. Eleanor Robson, the principal investigator of the Nahrein Network project at UCL. She encouraged visiting heritage cities in UK to have good experience in dealing with Iraq heritage.

Mrs. Macrae is administrating the archeology department in the City Council of York. Meeting with an expert holding such a position in a historical city was very useful as well. She mentioned that regulations were developed for the City Council in the 1990s and helped the city to keep its heritage. Recently, a new municipality was established in the historic part of Najaf, which is the first initiative step in Iraq. York City Council and its experience in managing historic cities can be a good example for the new Najaf municipality.

ArCHIAM, Centre for the Study of Architecture and Cultural Heritage of India, Arabia, and the Maghreb, is an interdisciplinary forum based at the University of Liverpool. Crossing traditional disciplinary boundaries, the Centre provides an exciting opportunity for the study of both historical and contemporary phenomena with the aim to develop theoretical positions but also practice-based research. A meeting in person was held with the ArCHIAM team to discuss the potential cooperation in cultural heritage projects. Last year, the ArCHIAM team worked with the University of Kufa on our Nahrein Network funded project: Heritage Buildings of Kufa. The team’s role was training the students on documenting heritage buildings. The training was online and an in-person meeting was necessary to introduce more cooperation potential. Three main issues were discussed, such as cooperation in research works, building capacity, and partnership in submitting for grants.

What are your future plans now that you are back in Iraq?

The project proposal was to design an action plan to be implemented by students at University of Kufa. The plan will contain training program for the students to learn them how to do inventorying for the intangible cultural heritage elements. Four communities are related to Najaf old city: pilgrims, scientific religious students, workers, and residents. Documenting of the chosen elements will increase the heritage awareness.

Dr Ali in front of the Wilkins Building

The Impact of Social and Climate Changes on Iraqi Earthen Buildings

By Zainab, on 3 January 2024

Written by Ammar Al-Taee

Mud as an essential material has been associated with Mesopotamia since the early maturity of civilization in the land now known as Iraq, with its earliest mentions in religious epics and myths. One of the first concepts that apparently occupied human thought was the origins of existence and the creation of humans. The Sumerians, as well as the Babylonians, considered mud the primary material from which humans were created, with this belief echoed in later Abrahamic ideas.

One of the key features of Mesopotamian construction and architecture was that, throughout the ages, it relied primarily on mud. The environment determined both types of building materials and construction methods, as well as architectural styles and designs. From these historical, ideological and environmental notions, earthen buildings, constructed as they were from mud, became crucially important to ancient Mesopotamia, representing an essential part of the identity of this early civilisation.

Earthen houses:

Today, the towns, cities and even villages of modern-day Iraq are primarily concrete in nature, as cement has become the most widely used basic construction material, at the expense of mud.

To discover why Iraqis have become reluctant to continue the country’s long traditions of relying on earthen buildings, we find examples of earthen houses still in use today. After a long search, we found a small village called Al-Samoud (Resilience) in Babel Governorate. This village still steadfastly preserves some of the ancient traditions of earthen buildings. We met Abu Abbas, the head of the village, who told us about local mud-built houses still in use today and discussed his own involvement in building earthen houses. However, he told us that because of developments in building materials and the popularization of cement – an economic material that can be prepared quickly, unlike mud, which needs specific mixtures and seasons to prepare it for construction – local people increasingly turned to cement.

Abu Abbas beside a traditional mud bread oven with one of his sons, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

His son Abbas believes there are other reasons for earthen houses falling from favour. The introduction of cement contributed to the gradual disappearance of craftsmen who specialized in making mud bricks and earthen plaster. The process of building mud bricks is similar, in principle, to the process of building fired bricks. However, building earthen structures requires specialist skills in preparing mud bricks, binding materials, and plastering methods, as well as expert knowledge of the timings and duration required to ferment mixtures appropriately. These processes are far from instantaneous, meaning that building earthen dwellings requires additional time and costs than constructing concrete buildings. In addition, earthen houses require annual maintenance to ensure they remain weatherproof, unlike cement which requires more minimal and sporadic attention. Abbas believes that dwindling local interest in earthen houses is not only a result of these practical aspects and loss of skilled and knowledgeable craftsmen but because people have also come to reject earthen houses as a symbol of poverty and low social standing.

A group of earthen houses that were abandoned by their owners after they moved to the city, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

Abu Abbas said that, whilst his son’s points were correct at the current time, building with mud bricks was previously a considerably cheaper option than cement as work depended on villagers helping each other. His perspective is that earthen buildings were linked to a strong, stable and mutually beneficial social environment. Abu Abbas also pointed out that, although the village is surrounded by earth, after several drought years, the decrease in groundwater levels and the increase in salinity has had an additional impact on the environment upon which this community, and even its social cohesion, long depended. “We are no longer able to farm or raise our livestock easily, as both our lives and the lives of our animals today depend on the water truck that stands next to my house,” he said. He views these environmental changes as the main reason for the migration of many village residents towards Iraq’s towns and cities, something which, in turn, has speeded up the disappearance of previously common building methods and customs.

The impact of such climate changes is not only limited to tangible heritage, such as the earthen buildings themselves, but its threat extends to intangible heritage. Traditional customs, social living, especially tribal social structures and the songs and oral traditions that have long been part of the fabric that binds communities together, are now also under threat.

Abu Abbas prefers earthen houses because they are cool in summer and warm in winter, in contrast to concrete properties which retain heat, something which is incompatible with the local climate, especially the soaring summer temperatures of central and southern Iraq. According to recent studies, average temperatures in the region have been consistently rising, something regularly described as a result of climate change. Although Abu Abbas is committed to preserving his earthen house and traditional way of life for the time being, he admits that, if consistent and reliable electricity and water supplies were to become available in his remote village, he would sacrifice his earthen house and replace it with a cement one, relying on air conditioners to cool it in the summer months.

The village river drought and layers of salt appear on the river banks, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

During our visit to the house of Abu Abbas, I noticed beds and chairs also constructed out of mud, which evoked many household scenes depicted on ancient Sumerian cylinder seals. The Iraqi Museum in Baghdad holds collections of miniature models of mud furnishings very similar to those seen in Abu Abbas’ residence. The mud bed was located in the outside courtyard of the house and is where Abu Abbas sleeps at night in the summer, under the stars, to enjoy the cooling dawn breeze. The survival of mud tools and furniture is linked to the presence of earthen houses, which will also disappear with the disappearance of earthen houses.

Earthen heritage monuments:

Many specialists believe that protecting this Mesopotamian heritage of earthen buildings, as well as all aspects relating to mud craftsmanship, is very important. The responsibility of protecting this cultural heritage falls primarily on Iraqi governmental and non-governmental institutions working with heritage, but Iraqi universities should also share this responsibility. To this day, departments of architecture, whether in Baghdad University or at Babil University, do not generally study the earthen architecture of Mesopotamia.

“There is no real interest in teaching the earthen architecture of Mesopotamia in Iraqi universities, and all we know about such earthen buildings is that they used mud to make mud bricks and added straw to them,” said Dima Saad Zabar, an architect who holds a Master’s degree from Nahrain University, Baghdad. “After my work documenting the Temple of Ninmakh in the ancient city of Babylon with the World Monument Fund, I realized the importance of this architecture, and I now believe it deserves to have a special section dedicated to its teaching in Iraqi universities.”

Dima is working on documenting the Ninmakh Temple, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

The Iraqi higher education system also faces an additional problem, as archeology departments countrywide lack specialists in teaching conservation. Despite this, there has been a recent trend towards lecturers encouraging students to write theses focusing on the maintenance of historic buildings and/or ancient artefacts. There have been reported instances of professors specialising in, for example, Islamic arts and having no practical field experience in maintenance, supervising theses on the preservation of ancient buildings or artefacts. This not only threatens to undermine the value of Iraqi qualifications but, in the future, could put valuable archaeological sites and artefacts in danger. Graduates with backgrounds lacking in sound historic preservation principles, an understanding of international practice, and practical experiences may one day be responsible for maintaining Iraq’s precious heritage.

During a 2015 overland trip visiting Iranian heritage and religious sites, which encompassed Mehran, Khorramabad, Arak, Qom, Nishapur, Mashhad, Yazd and Isfahan, I found that earthen buildings and related crafts received significant care and attention. Furthermore, I discovered that Iranian plans for managing, preserving, and protecting earthen heritage sites differed greatly from our limited capabilities in Iraq, where heritage management and maintenance has long been a low priority for successive governments.

Today, the earthen monuments in Iraq, and in Babylon in particular, suffer from many problems that urgently need to be addressed. The first of these is the lack of overall management plans for individual sites, as well as a lack of any comprehensive countrywide maintenance strategies. Another problem is one of recent history. Between 1979 and 2003, monument maintenance relied on direct implementation of maintenance work without any prior studies for long-term viability of this and without suitable consideration of materials used. Such prior studies would have represented not only a doctor’s diagnosis of a disease but also could have identified appropriate methods of treating it in the long term.

Part of Babylon’s inner walls after they were maintained with baked bricks and cement in the eighties of the last century, Credit: Ammar Al-Taee

Therefore, previous maintenance work undertaken on earthen monuments included reinforcing ancient structures by filling them with hundreds of tons of cement, concrete, fire bricks and assorted other materials. For example, more than 40 different non-earthen building materials were used on the Ninmakh Temple alone in order to keep it standing. Whilst this gave an outward appearance of the integral strength of the temple, during a Babylon International Festival, in fact the use of modern construction materials meant that its interior was carcinogenic to the structure itself.

Unfortunately, since 2003 and up to the present day, the reality of Iraq’s earthen monuments has become bitterer. Valuable ancient buildings and sites have suffered from two decades of near-total neglect. The result of an ongoing lack of regular maintenance, the impact of climate change and human interventions, and the negative impact of former inappropriate modern materials deployed during maintenance is that large parts of earthen monuments have been lost.

Today, Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH) which is the institution responsible for these monuments does not have the funds needed to maintain them. When funds are available, usually at the end of the fiscal year (in the months of October and November) these are very modest and must be spent within these two months. The question is: What can be accomplished in just two months?

A project to maintain parts of just one of Ancient Babylon’s temples in an appropriate scientific manner require at least two years. Here we return to the words of Abu Abbas from the village of Al-Samoud: “Building with mud requires not only prior preparations but also specific seasons for the processes.” Long-term successful maintenance using sympathetic materials requires years not months. In addition, the effects of the climate changes seen in the region over the last few years have further complicated maintenance operations as base materials – including water and earth – now have higher salinity and a greater presence of pollutants. Processes to make sympathetic maintenance materials now have to include more careful soil selection, and the purification of both water and earth before construction materials can be made, which takes still more time.

Another challenge – also seen in Al-Samoud village – is that the mud brick craftsmen and masons have all but disappeared, abandoning their former careers due to the prevalence of cement, fire bricks and concrete in not only construction but also building maintenance.

A group of young Iraqi masons, after rebuilding the the Cella room of Ninmakh temple, Babylon. Credit: Ammar Al-Taee

Today, those specialists and experts have grown old, and their health does not often allow them to practice this arduous craft. Therefore, since 2018, the World Monument Fund has focused on training a new generation of specialists by selecting 10 local youth from villages surrounding ancient Babylon to become mud brick and earthen craftsmen, to fill the gap that the cement created it. The goal is for these young people to have the skills to be able to maintain the earthen buildings in Babylon in the event that Iraqi institutions concerned with heritage preservation ask them to do so in the future.

Although undoubtedly a valuable initiative for Babylon, it does raise concerns about what the future might hold for the thousands of other earthen heritage sites spread across Iraq.

Egyptian architect Mohammad Tantawi, who specializes in earthen buildings, is working with us today to maintain Babylon’s Temple of Ninmakh. He believes that traditional adobe (clay) buildings in Egypt face similar problems to those seen in Iraq, both from maintenance and climate perspectives.

Preserving and maintaining earthen heritage and even reviving traditional building practices in the Middle East and North Africa is something largely dependent on international universities and maintenance missions. Unfortunately, in light of the apparent inability of national governments and institutions to prioritise heritage and provide appropriate levels of financial and practical support and expertise in this field, foreign institutions remain a key supporter in the fight to preserve this cultural heritage from further ruinous deterioration or even extinction.

Interview with Niyan Ibrahim Recipient of the 2022 Graduate Studentship

By Zainab, on 7 December 2023

Meet Niyan Hussein Ibrahim, the first recipient of the UCL-Nahrein Network Graduate Studentship. Niyan recently completed an MSc in Sustainable Heritage at The Bartlett Institute for Sustainable Heritage and has secured a PhD place in the same department, fully funded by the Nahrein Network.

Tell us a little about yourself.

My Name is Niyan Ibrahim. I am from Sulaimani City in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. I have both my BSc and MSc degrees in City Planning from Sulaimani Polytechnic University. I worked as an Urban Planner at Sulaimani City Municipality and at the Sulaimani Directorate of Antiquities. I am also a co-founder and deputy head of the Cultural Heritage Organization for Developing Cultural Heritage (CHO), funded by the Nahrein Network. I have worked with the heritage neighborhoods within Sulaimani City and on other aspects of urban planning within the different departments I worked in. That’s why I am trying to have a disciplinary research approach because of my different carrier experiences.

Niyan at UCL’s Japanese Garden Pavilion

How was your experience studying at The Bartlett?

Studying at The Bartlett is a wonderful opportunity, as it is UK’s largest and most multidisciplinary school for studying and researching the built environment. While conducting my MSc at the Institute of Sustainable Heritage within The Bartlett, I had a great opportunity to cover various aspects of heritage studies and conduct practical work and research on different projects.

How is learning in the UK different from Iraq?

Learning in the UK is different from Iraq, in the sense that it is more practical and more based on empirical studies, and the courses are more appropriate for the working environment. You don’t just attend lectures which are taught by your professors, but they collaborate with people who are conducting the work on the projects, and they are also the ones who will deliver it to you. So it is a mix of academic and research education and empirical studies.

What was the focus of your Master’s research?

The focus of my Master’s dissertation was ‘Assessing the Level of Sustainability of Public Policies Regarding Cultural Heritage in the Kurdistan Region Iraq’, in which I aimed to assess the state of public policies regarding cultural heritage in the Kurdistan Region. This field of research is quite novel in general and for the context of Iraq especially.

Niyan at UCL’s Student Centre

Has completing this Master’s degree shifted your research interests and how?

Completing the Master’s provided me with a clearer perspective and narrowed down my research objectives. Before finishing the master’s program, I had a general proposal for my PhD studies. I knew what I wanted to achieve but not exactly how. But after undertaking the modules I had a better vision, and I knew exactly what I wanted to study and how to conduct my research.

Tell us more about your PhD research proposal and how you see your career benefitting from a PhD.

It is about exploring the relationship between sustainable heritage management and public transportation. There is a gap in this research area, and it has not been explored extensively. So as a researcher, it naturally gives me the opportunity to contribute to a novel research field that has yet to be explored. And in the context of a developing country with a rich heritage like Iraq, this kind of research is needed to inform policymakers and direct the country towards the sustainable development agenda through managing its heritage. So as an urban planner and a heritage professional, I will develop my career in many different aspects and levels.

Follow Niyan on X: @NHusseinu

Remembering the ‘Camp Speicher‘ atrocities

By Mehiyar Kathem, on 6 December 2023

Not all atrocities are remembered equally. Some are forgotten, or deliberately erased from public memory, buried like the victims. Sites of memory, including monuments, art and other public depictions and displays, can help society remember and negotiate traumatic pasts.

On 13th June 2023, the provincial government of Wasit in Iraq unveiled a memorial to the events that unfolded in and around Tikrit’s Camp Speicher in 2014. The military site was renamed by the US Occupation after Michael Scott Speicher, a US pilot shot down by the Iraqi Army in the 1991 Gulf War. Camp Speicher was used from 2003 up to the withdraw of the US Army from the country in 2011 where it was then renamed the Tikrit Air Force Academy. In the Iraqi public sphere, the name Speicher however has lingered and become indelibly associated with the military camp and the unfolding atrocities.

In June 2014, DAESH rounded up some 2000 student air cadets who had tried to escape the disorder and collapse in Iraq’s security command chain. After Mosul fell to DAESH, Tikrit and its environs, including Camp Speicher became under the control of local tribes who proclaimed allegiance to the armed group. Student air cadets, most of whom were between the ages of 18 and 24 years fled hurriedly on foot in civilian clothes. They were told by local tribes that they would be offered a route to safety. Sunni air cadet trainees were freed and the Shia among them were quickly rounded up by Tikrit’s tribes and marched to trucks that would then take them to Saddam Hussein’s former palace compound, overlooking the Tigris river.

They were divided into groups and distributed between Tikrit’s main tribes, with each participating tribe now free to enact the most grotesque forms of torture on those in their possession. After those ordeals, some of which lasted for two or three days, most were shot and then dumped in shallow trenches in and around the palace compound. On another key location, prisoners were executed at the edges of the river Tigris in the palace compound. The presidential compound was effectively transformed into a factory of torture and death.

Former Presidential Palace Compound. At the one of the sites of the massacres. 2023.

The Speicher Memorial in Kut, the provincial capital, is one of Iraq’s first attempts to remember those atrocities in the form of a physical, public-oriented structure. The new memorial in Kut is inspired by Freedom Monument – an iconic emblem in central Baghdad’s Tahrir Square. Designed by renowned artist Jawad Salim, Freedom Monument represents notions of justice and dignity through a collective storytelling of Iraq’s modern and ancient history. Whereas Freedom Monument represents Iraq’s self-determination, calling to the stories of its peoples and rich histories for inspiration, this new memorial depicts the suffering of victims of the Camp Speicher massacres.

Wasit, Kut. 2023.

The memorial weaves this event’s traumatic memories, derived from those graphic images captured in videos and photographs posted on social media by DAESH. The spiralling cone structure, not unlike that of Samarra’s famous minerat, is dotted with artistic pieces made of brass depicting scenes of the ordeals endured by the victims. The memorial depicts handcuffed and blindfolded prisoners, some kneeling on a staircase adjacent to a palace building where their bodies would then be dumped into the river.

A site of execution, at the former Presidential Palace Compound. 2023.

Painting by Iraqi Artist Ammar Al-Rassam of the former presidential palace adjacent to the Tigris river, Tikrit.

This is the not the first attempt to memorialise the Speicher massacres. Since 2014, families from different parts of Iraq would visit on every 12 June the former presidential palace compound. A monument that had been erected at the palace complex displays three mothers, one standing defiant and two wailing over a mass grave containing replicas of human skulls and bones strewn on the ground. In addition to recognition and remembrance, those now annual visitations serve group mourning. In the absence of any form Iraqi or foreign psychosocial support – particularly for victim’s children, wives and mothers– the gatherings have assumed a site for catharsis, even in a situation of an absence of justice for victims and where over 700 air cadet students are still missing.

A ‘Speicher Camp’ memorial at the former Tikrit Presidential Compound. Tikrit, Iraq.

Other than families’ own ad hoc efforts to print and display photos of their children, up to the present moment, this was the only memorial to the camp Speicher atrocities in the country. Printing and raising a photo of their missing or deceased loved ones has been a common way families have sought recognition for those atrocities. Significantly, and as simple as this act is, it is perhaps one of the few ways those mostly impoverished and marginalised families can ask for a semblance of justice expressed through society-oriented remembering.

Former Presidential Palace Compound, Tikrit. June 12th 2023.

A woman whose son was killed by Daesh collapses at the Speicher Memorial site in Kut, Wasit. June 2023.

On a recent visit to the former presidential palace, Victims of Camp Speicher, a registered Iraqi non-governmental organisation made up of family members whose sons were killed, discovered an unidentified human skull lying in a heap of earth next to a staircase. Human remains continue to pop out of the ground on the site as a result of rain and wind. The Victims of Camp Speicher Organisation is Iraq’s only non-governmental organisation working to document what happened. It is made up of members of families of those killed by DAESH. Abu Ahmed, the director of the Baghdad office, retrieved his son’s body from one of the mass graves in the Tikrit Presidential compound.

Photo from Sadiq Mahdi at the former presidential palace, Tikrit. 2023.

Many identified mass graves have not been excavated and those that have been opened lie without any labelling or proper, professional or even basic demarcation, a sign of the dysfunctional nature of the management of this case. Indeed, anyone visiting the site could easily be walking over a mass grave without knowing it. The presence of unidentified human remains and absence of informational panels or professional management of mass graves is symptomatic of the wider neglect victims and their families continue to endure.

A mass grave at the former Presidential Palace Compound. Tikrit, Iraq. 2023. Photo: Sadiq Mahdi.

The absence of professional and organised documentation is indicative of forgetting of the ‘Camp Speicher’ atrocities. Similarly, US-European governments and their funding agencies and organisations in Iraq have up to recently shown little interest in the case. Their interest has focused instead on one section of Iraqi society, namely the plight of Iraq’s Yezidis. US-European funding has imposed and reinforced on Iraq a ‘hierarchy of suffering’ where some groups or sections of Iraqi society are seemingly more worthy of support than others.

Through a UN Security Council resolution in 2017, the United Nations Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh/ISIL (UNITAD) was established. A year later, a director was installed. UNITAD’s mandate is seemingly meant to serve the people of Iraq, namely through ‘collecting, preserving and storing evidence’ on the crimes of DAESH. In a recent discussion at the UN, the Iraqi Government has underlined its unwillingness to extend UNITAD’s mandate, with a closure date of September 2024.

A central reason cited by Iraq’s representative at the United Nations for this decision has been that UNITAD has shared information and data with European governments but not with the Government of Iraq, instigating questions about violations of Iraq’s sovereignty, ethics pertaining to how victim-related and also Government-obtained information is used and who it is shared with and more broadly issues of accountability.

The year 2024 will mark ten years since those atrocities were enacted on the people of Iraq. It will be a time of reflection and hopefully an opportunity to better explore how memorialisation can assist its people in recovering or at least coming to terms with a traumatic recent past.

The Zindan Archaeological Site in Diyala

By Mehiyar Kathem, on 5 December 2023

Written by Mehiyar Kathem and Ahmed Abdul Jabbar Khamas

Iraq contains tens of thousands of archaeological and heritage sites. One of its most significant though little known sites is the Zindan Archaeological Site in the province of Diyala. The Zindan, a Persian name for a prison, was one of the Sassanian Empire’s largest and significant fortresses. It lies about 80 km northeast of Baghdad or about 30 km from Baquba, the provincial capital of Diyala. More specifically, the Zindan is located about 12 km east of the city of Muqdadiyah, and near the village of Al-Jejan.

Historically, the site was on the Great Khorasan Road, an inter-city network connecting Asia with the Middle East and further afield. The size of the Zindan, measuring 40,800 sqm in total, is commensurate with its significance as a key component in Sassanian security infrastructure provided along the Great Khorasan Road. The Zindan is considered as one of the facilities and extensions of the Sasanian Royal Capital City of Dastgird, located about 5.6km north of it. The brick-structure is 502m in length, 14.5m in width and 16m in height. It has 14 pillars or towers, of which 10 are still standing.

Before the commencement of work

After the commencement of work

The Zindan Archaeological Site is located in Diyala’s rich agricultural plain, in the middle of the Lower Diyala river basin, watered until recently by the Diyala River that flows into the country from Iran. In recent years, Iran has redirected its own water resources away from Iraq. The agricultural areas adjacent to the Zindan have consequently turned from a green, fertile land supporting a diverse and large crop output for Iraq’s population to ocherish fields of dry and increasingly fallow farms.

In 2021, as director of the Diyala’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH) office, Ahmed Abdul Jabbar Khamas undertook a project to safeguard and research the Zindan. This was the first initiative to investigate the site since 1957-1958, when Robert McCormick Adams, an archaeologist-anthropologist, undertook a survey of the site and Diyala’s surrounding archaeology. That research and work to document Diyala’s archaeology was formative for a field that was increasingly using new methods of documentation, namely arial-based surveying. It is worth noting that work carried was out on the site by Mr. Claudius James Rich in 1820. Rich stated that this site could be a royal shrine.

SBAH sought to protect the site by re-installing a previously damaged 2000m fence wall. That would be the first line of defence for safeguarding the site from vehicles and other infringements on the structure, not least by the expansion of farming. Khamas’ team would then unveil the structures of the Zindan by removing some 17,000 tonnes of material accumulated on the site over the past few centuries.

Once that had been completed, the SBAH team were able to better understand the architectural structure of the Zindan, which was surveyed for documentation and further research. Several new structures within the site were discovered and some 68 artefacts were retrieved and submitted for cataloguing at the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. Throughout 2021 and 2022, a total of $300,000 was spent by SBAH on the project and 140 temporary workers, most from the district of al Muqdadiyah itself, where the Zindan is located, were employed.

Workers from the nearby villages and towns in Diyala

Work challenges included the presence of snakes and scorpions, posing a threat to workers on the site. The site itself is not connected to local electricity grids and water networks. Access roads are not paved, making it difficult to reach the site on rainy and muddy days. A service infrastructure would need to be implemented before the site can better welcome visitors. The site however is open to tourists and there are a growing number of residents, numbering on average 300 or so per week, from Diyala itself who are visiting the site. As of yet there are no information or educational panels.

The discovery of arches and Iwans at the Zindan.

The original brick floors.

A view from inside the Zindan.

The re-discovery of the Zindan by Iraqi heritage authorities and archaeologists marks a major turning point in the safeguarding, study and celebration of Iraq’s neglected Persian Empire heritage. Such Iraqi-led initiatives are central to strengthening the country’s own body of knowledge and research regarding its past and that of the wider region. Significantly, SBAH, led by Ahmed Khamas were also recently able to discover the Sassanian-era royal city of Khosrow that had been the residence of King Khosrow and his armies that would eventually, like the Zindan itself, be attacked and looted by the Byzantine Emperor Heraclious. Evidence of that attack on the Zindan are visible on its structures and walls and require further documentation and study.

This Sassanian Empire era fortress also paved the way for SBAH Diyala to survey the historic site of Jalula, also on the Great Khorasan Road, where Islamic armies of the Rashidun Caliphate had defeated a Sassanian garrison that eventually led to the capture of historic Mosul and the spread of Islam in the region and into ancient Iran itself. The Zindan forms a central part of this story and could potentially be registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site along with other key sites in the region.

For connecting with communities, SBAH organised a cultural event that invited nearby villagers, farmers, government workers and other constituents of local society to an opening of the Zindan, which helped raise awareness of its historical significance and the work that had been conducted.

A community event was organised to raise awareness of the site and to celebrate the completion of this initial phase of the project.

The heritage of the Zindan and the wider Diyala region is an assemblage of the histories of ancient Iraq, Iran and the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the wider Muslim world. The Zindan as part of wider complex of archaeology could make for a superb educational and tourist location. The site is also potentially significant for historians of early Islam.

Considering the site’s diverse and rich history, it could be a vector for Iranian archaeologists and historians to work with their counterparts in Iraq. This would help reverse or address decades long neglect in Iraq’s university system of the country’s Persian and Ottoman heritage past. New collaborations would be welcome, not least to build networks of research and knowledge within the region and help diversify Iraq’s body of archaeology. Such possible and productive research partnerships, formed around shared heritage sites, could help center knowledge production within the region.

SBAH’s relatively small initiatives to invigorate a long-forgotten component of Iraqi cultural heritage bodes well for the construction of an Iraqi-oriented school of archaeology and history, not least one that is determined and shaped by Iraqis themselves.

All photos were taken by Ahmed Abdul Jabbar Khamas.

Ceramic Craft in the Babylon Province

By Zainab, on 30 November 2023

Written by Ammar Al-Taee

Ceramic is one of the oldest crafts in Mesopotamia, having its roots in the depths of prehistory, and it represents the extent of human profound harmony with earth, a versatile material that was formed by man for many uses. Ceramic was known in the Sumerian language as bakhar, synonymous of the Akkadian pakḫāru, which became fakhar in modern Iraqi accent.

Four methods to produce ceramic have been listed so far in Iraq.

In the beginning, ceramists shaped clay using fingers to form the sides of the pots. In a second period, they used a different method, manufacturing separately the base, the sides, and neck of the pot, and then connecting them together.

The inhabitants of Mesopotamia used a third method for making pottery, proceeding by placing clay rolls in spirals one on top of another, until reaching the required height. These spirals were then further hydrated and pressed to obtain the desired shape. This method is still widely used in Iraq, especially in the local bread oven industry.

The fourth method implies the use of a wheel. Clay dough is placed on a disc turned by a wheel put in action by the artisan with his foot. The artisan uses then his hands to form the shape of the pottery. This method is the best one to produce pottery, in terms of speed and quality. The first traces of the pottery wheel were found in the city of Uruk, in the south of Mesopotamia: a seal dating back to the fourth millennium BC contains scenes representing the fabrication of pottery. According to the cuneiform written texts, the owners of this profession used to operate in workshops in the cities.

At present, ceramists became very rare. The craft of pottery production, like other crafts traditional and techniques of the ancient cities of Mesopotamia, is in rapid decline.

The ceramist Aqeel Al-Kawaz in Borsippa, photo by Ahmed Hashim

Aqeel Al-Kawaz, a professional ceramist from Borsippa in the Babil province makes pottery for various uses in different shapes and colors. The clay he uses comes from different provinces in Iraq such as Kirkuk, Diyala, Najaf, Samawah and, of course, Babil. The reason for the variety of clay he uses is for artistic purposes, as some pottery pieces are preferably made from the soil of certain provinces.

Some of the pottery that Aqeel is currently producing, is used to preserve food and water, but he focuses on the most requested pottery in the Iraqi market: ceramic drums. He also produces a kind of small coloured jug that symbolizes female and male kids. These are symbolically used in commemoration of the birth of the Prophet Zakariya, to keep evil away from children.

The clay is prepared in advance, collected in tubs during the summer. He sometimes adds cow bones in the basins to increase the quality of the clay. Based on his experience, Aqeel believes that bones help to spread a type of bacteria, which makes the clay smoother and better workable.

Although the craft of making pottery seems very easy to those who see Aqeel making an object in a few minutes and with a few swift movements, reaching this skill is difficult and requires long training and endless patience.

Ceramic drums, photo by Ammar Al-Taee

Nowadays Aqeel works alone in his modest workshop and fights to preserve the craft, as he is the only member of a family of artisans who kept the craft alive. Before I left his workshop together with Zainab, Nahrein Network’s media officer, he told us “I’m the last pottery maker in the Babil province, and my children refuse to work and even to learn this craft”. He is not optimistic about the future of the pottery profession, not only in the Babil province, but in all of Iraq.

Finally, one of the worst challenges the pottery craft is called to face, is that it is considered a symbol of poverty and primitiveness.

For all these reasons, there’s an urgent need to create training and education both to increase the numbers of professional artisans, to revive the countless crafts and skills necessary to maintain precious elements of the local heritage, and to sustain the still operating artisans with governmental support.

These actions together will also help to contain the threat represented by the introduction on the market of foreign pottery, which is sold at a much cheaper price.

Pottery is an environmentally friendly material, it is easily renewable, opposite to plastic or metal cans that cause great pollution at global level. Drinking water from- or cooking with pottery is healthy and recommended. Moreover, pottery is a natural water-cooling tool used in the countryside in Iraq to reduce the impact of the summer heat, helping to overcome power outages occurring for many hours every day.

Ceramist Aqeel Al-Kawaz in his Borsippa workshop, photo by Ahmed Hashim

Preserving traditional crafts in Iraq is a challenging effort that requires continuous support to create an environment that guarantees financial and social stability for artisans. Therefore, to ensure the survival of these memories and crafts, it is necessary to disseminate community awareness on the importance of preserving this heritage and increasing the numbers of pottery craftsmen.

Christian Cultural Heritage in Mosul

By Zainab, on 31 October 2023

We talk to Dr Abdulkareem Yaseen Ahmed, Lecturer in Linguistics at Diyala University. Dr Abdulkareem held a Nahrein – BISI Visiting Scholarship at University of Leicester. Dr Abdulkareem’s project is titled Christian Cultural Heritage in Mosul and is under the supervision of Dr Selena Wisnom.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and your background.

Dr Abdulkareem Yaseen with Professor Eleanor Robson at UCL

My name is Abdulkareem Yaseen, a lecturer at University of Diyala. My academic journey took me to the United Kingdom, where I achieved an MA from the University of York and subsequently completed my PhD at Newcastle University in 2018. Recently, I have successfully concluded a Nahrein Network/BISI-funded project in my role as a co-investigator, centered on the intricate process of identity reconstruction within the war-torn region of Karma, situated in Anbar, to the west of Iraq. This project nicely aligned with my research background, as I have previously engaged with the culturally rich community of Mosul.

What is your project about?

Well, my current project has brought me to the University of Leicester, where I’ve embarked on a mission dedicated to the preservation of the intangible cultural heritage of Mosul’s Christian community. This project is kindly supported by the Nahrein Network, based at University College London, as well as The British Institute for the Study of Iraq. Within the framework of this project, I have delved deeply into the intangible cultural heritage of Mosul’s Christian community and the considerable challenges it confronts. My research findings underscore the pivotal role played by oral traditions and dialects within the cultural heritage of this community. Moreover, I’ve illuminated how conflicts and socio-political turmoil have led to the decline of certain aspects of this intangible cultural heritage. Nevertheless, this project offers a ray of hope by outlining a comprehensive approach aimed at safeguarding and promoting the intangible cultural heritage of Mosul’s Christian community.

How was your stay in the UK?

In fact, my 8-week stay in Leicester has opened doors to new research possibilities and strengthened my commitment to safeguarding the cultural heritage of Mosul’s Christian community and beyond. Everyone at the Nahrein Network as well as the host institution (University of Leicester) has played a pivotal role in ensuring my stay was productive and enjoyable. I can’t thank them enough for what they did for me.

Have you had promising conversations or collaborations with colleagues?

During my stay in Leicester, the scholarship has undeniably broadened my horizons in multiple dimensions. Firstly, it has exposed me to a diverse community of researchers with a wide array of research interests. Interacting with these scholars has provided me with fresh perspectives and invaluable insights into various aspects of heritage preservation and cultural studies. These interactions have not only expanded my academic horizons but have also enriched my personal growth. Moreover, the Department of Archaeology has been a hub of expertise in heritage-related fields. Working closely with specialists from different research backgrounds related to heritage has given me an up-close look at their methodologies and approaches to preserving both tangible and intangible cultural assets. This exposure has deepened my understanding of the multifaceted challenges and opportunities involved in safeguarding cultural heritage. The vibrant academic environment at the University of Leicester has allowed me to engage in numerous meetings and gatherings where ideas and experiences were freely exchanged. So, I feel incredibly fortunate to have had the opportunity to engage with such fantastic individuals.

How do you plan to further your research once you’re back in Iraq?

Looking ahead, my ambitions extend beyond the boundaries of my initial project. I intend to expand the scope of my research to encompass a broader array of communities of interest. In particular, I envision a new chapter in this project that will delve into the rich history and heritage of the Jewish communities in northern Iraq. By doing so, I aim to create a more comprehensive and inclusive portrayal of Iraq’s cultural heritage landscape, shedding light on the multifaceted tapestry of traditions, narratives, and legacies that have shaped this region over centuries. This will not only deepen our understanding of Mosul’s Christian community but also contribute to a more holistic appreciation of the diverse cultural heritage that defines Iraq.

Dr Abdulkareem at UCL’s Japanese Garden Pavilion

How will your scholarship help you with your research?

Upon my return, I am wholeheartedly committed to forging enduring collaborations with the Christian community of Mosul, building upon the invaluable connections I’ve cultivated with the local residents while conducting my project. These relationships have not only enriched my understanding of their cultural heritage but have also demonstrated the genuine commitment of the community to preserving its traditions.

Reviving the Local Identity of the City of Basrah

By Zainab, on 25 September 2023

We talk to Dr Hamed H. Samir, Head of Architecture Department, Collage of Engineering, University of Basrah. Dr Hamed held a Nahrein – BISI Visiting Scholarship at University of Loughborough. Dr Hamed’s project is titled Reviving the Local Identity of the City of Basrah and is under the supervision of Dr Sura al-Maiyah.

Tell us about more about your project.

Dr Hamed with “Auto-Icon” of philosopher and reformer, Jeremy Bentham at UCL

Built heritage conservation is essential in post-war areas. In recent years, Iraqi traditional architecture has been deeply affected by several wars, challenging the cultural memory of local people.

My research considers Basra as a pilot case study. Basra is classified as a city rich in cultural heritage. In particular, the canals are a unique feature of the city. Within Iraq, Basra holds the nickname of “Venice of the East”, surrounded by its distinctive architectural identity. Basra today faces urban decay and is losing its architectural heritage and identity in a severe way.

A significant problem is the continuous altering of traditional architecture. The value of Basra’s built environment and its architectural heritage is absent from the local residents. This has contributed to losing countless historical buildings and the unique Basra charm.

The aim of my research is to explore how the legacy of Basra’s past can be transmitted to future generations. My project focuses on digitally documenting the tangible and intangible heritage of Basra. I am hoping to create a digital library to revive the collective memory of residents and to raise awareness regarding the value of Basra’s heritage.

How was your stay in the UK? Did you have promising conversations with colleagues?

It was an amazing experience to be in the UK. I got the chance to meet and work with many colleagues working in similar projects from across the world. In addition, I had the opportunity to visit labs and got experience on the newest cutting-edge tools for heritage documentation.

The colleagues are friendly and very helpful, they were always available to listen and discuss my project and constantly giving feedback. I believe that all this will no doubt lead to developing a solid project and reducing the challenges and barriers.

How will your scholarship help you with your research?

As a researcher, the scholarship in the UK has given me the opportunity to learn the newest technology and tools, such as laser scanning and photogrammetry. In addition, this scholarship has improved my skills regarding the new heritage documenting tools and how to use it. This is very necessary to my project. Moreover, in order to set a plan to create the digital library for Basra city heritage, the interaction with the experts in this field is much required, and this was achieved during my stay in the host university as well as other institutions in UK.

How do you plan to further your research once you are back in Iraq?

The future plan for me after finishing my scholarship and returning to Iraq will focus on creating a digital library for the heritage of Basra city. I believe this library will enhance the knowledge of young architects. In addition, I hope this will raise the awareness of the local people and revive the collective memory of Basra’s heritage and traditional architecture particularly the younger generations.

You can watch Dr Hamed’s seminar titled, Safeguarding the diversity of cultural heritage in Basrah on our YouTube page.

Close

Close