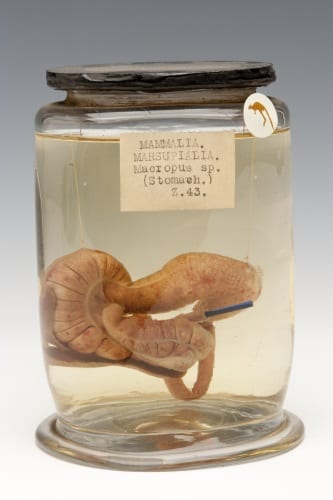

Specimen of the Week 363: The kangaroo stomach

By Christopher J Wearden, on 19 October 2018

After nearly a year working at the Grant Museum I realise I have become accustomed to aesthetics of my working environment. Decorations in your typical office might include team photos, prints of inspirational quotes and once a year, some tinsel. Here our walls are decorated with skulls, intestines and pickled reproductive organs. An interaction between a visitor and myself might involve them asking me ‘what is THAT??’, only for me to matter-of-factly reply ‘oh, that’s a bisected seal nose’. Not all interactions are so cordial however; when one visitor recently told me that our displays were ‘gratuitous’ I gently reminded them that our museum is primarily a teaching collection, meaning students across a wide range of disciplines often look at certain ‘unappealing’ parts of an animal in great detail. I hope that by writing about today’s specimen I can demonstrate why we have these ‘gratuitous’ objects on display, and what they can teach us about animals. Okay readers let’s hop to it, it’s the…

***Kangaroo stomach***

Kangaroos are marsupials which belong in the genus Macropus, part of the Macropodidae family. Marsupials differ from placental mammals (apes, dogs, cats etc.) in that they have a short gestation period and give birth to relatively undeveloped young. The young (in this case a ‘joey’) then spends a period suckling on the mother’s teat, where it gains the necessary nourishment to develop and grow. There are four known species of kangaroo, all of which are native to Australia; the red kangaroo, the the eastern grey kangaroo, the western grey kangaroo and antilopine kangaroo. Well-known physical characteristics shared by all kangaroos include their large feet, long tails and of course their pouch. It turns out they are very interesting on the inside, too. Today’s blog will explore how their stomachs are adapted to their diet and the challenging climatic conditions they live in.

The Kongouro from New Holland (Kangaroo), George Stubbs (1772). ZBA5754 (L6685-001). National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Difficult to digest

All terrestrial kangaroos (kangaroos that live on the ground) are strict herbivores. They regurgitate and re-chew digesta on an occasional basis which, to the informed reader, might sound an awful lot like rumination. However this process – known as ‘Merycism’ – differs from rumination in a number of ways. Rumination is the process by which cows, sheep and goats extract nutrients from their food, regurgitating partially chewed food and eventually swallowing it again.(1) Kangaroos however do not need to regurgitate their food, and do so only occasionally.(2) A study conducted by the University of New South Wales Animal Care and Ethics Committee (ACEC) found that merycism seemed to cause kangaroos distress and tended to occur when they were fed pellets, as opposed to hay. They do however share some similarities with ruminants in the way their stomachs break down food.

Strong stomachs

Kangaroos have two stomach chambers; the sacciform and the tubiform. The sacciform chamber contains bacteria, fungi and protozoa that begin the fermentation process necessary for digestion. During this process kangaroos may spit up bits of undigested food to be chewed and then swallowed again, much like a cow. As the food ferments, it passes into the kangaroos second stomach chamber, where acids and enzymes finish digestion. (3) Kangaroos therefore have modified stomachs which allow them to break their food down although this is all done in one stomach with two chambers, not four separate stomachs like a cow. Their specially designed stomach allows them to extract 70% of the energy from fibre digestion (4), which is more than cows.

Kangaroo eating by Jervis Bay via Wikimedia Commons. CC-BY-SA-4.0

Not a drop to drink

Kangaroos need very little water to survive and can go weeks, or even months, without drinking water. As all species of kangaroo experience frequent dry spells this adaptation is crucial to their survival. You may be asking at this point how they survive with very little water in such a challenging climate and the answers lie, once again, on the inside. By digesting their food slowly they are able to draw every last drop of moisture from their food before disposing of the waste.(5) Additionally, they are crepuscular animals which are most active at dusk and dawn. By limiting their activity to these cooler periods they are able to conserve water.

Out of gas

Another way in which kangaroos different from ruminants is that they produce almost no methane during digestion. The bacteria in their stomach turns hydrogen into acetate, not methane. A study conducted by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) investigated this process, with project leader Professor Mark Morrison stating a long term goal of redirecting feed digestion in livestock away from methane formation by using the bacteria in kangaroos which help produce acetate.(5) The impact the beef industry is having on the environment is well-documented (this BBC article suggested we need to cut out consumption by 90%) and many Australians are now looking at kangaroo meat as an environmentally friendly alternative.

I hope my blog today has helped you understand why we have objects like kangaroo stomachs on display. By comparing these specimens with others we can explore the diversity of the animal kingdom and look at different parts of animals in great detail. Basically it’s not all about displaying the gory bits – but we do like that too.

Chris Wearden is the Visitor Services Assistant at the Grant Museum

(1) http://www.cattle.ca/assets/Uploads/232d540861/ruminants.pdf

(2) Vendl, Catharina, ‘Mercyism in western grey (Macropus fuliginosus) and red kangaroos (Macropus rufus), Mammalian Biology, September 2017, p. 1

(3) https://sciencing.com/digestive-system-kangaroo-8638441.html

(4) Dawson, Terence J, Kangaroos, CSIRO Publishing, 2012. p. 132

(5) https://sciencing.com/digestive-system-kangaroo-8638441.html

(6) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-13946941

2 Responses to “Specimen of the Week 363: The kangaroo stomach”

- 1

-

2

Do Kangaroos Eat Meat? (And Eat Dogs?) – Animal Giant wrote on 20 October 2022:

[…] islands. Each species occupies a particular habitat and will have a diet that is mainly accessible. Kangaroos have two stomachs and chew their food twice before proceeding with digestion. But do kangaroos eat […]

Close

Close

Hi there. I am an agricultural education teacher in Colorado in the USA. I enjoyed this article and used it in one of my classes; however, I was dismayed to see a mistake in the fourth paragraph under the subheading “Strong Stomachs.” The sentence reads, “Kangaroos therefore have modified stomachs which allow them to break their food down although this is all done in one stomach with two chambers, not four separate stomachs like a cow.”

It is a common misconception that cattle and all ruminant animals have four stomachs. In fact, however, ruminant animals actually have one stomach with four separate chambers: the rumen, the reticulum, the omasum, and the abomasum. Therefore – kangaroos and cattle both have multi-chambered stomachs, but they only have one stomach. There are dozens of educational websites to back me up. Here is just one link: https://beefskillathon.tamu.edu/cows-digestive-system/

I respectfully ask that you fix this error. Agricultural literacy is a terrible challenge that all agriculturalists face, and institutes of higher education like UCL have a responsibility to portray truth in all facets.

Thank you.