Specimen of the Week 341: The Bark Scorpion

By Jack Ashby, on 4 May 2018

This week’s Specimen of the Week is a guest edition by Front of House Volunteer and UCL Student of History and Philosophy of Science, Leah Christian.

As a native of Texas, this week’s Specimen of the Week is one that is always near and dear to my heart and occasionally in my shoes. And my sheets. And my hair. This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

** The bark scorpion **

There are many types of bark scorpion. The genus Centruroides contains roughly 70 species, many of which have some form of “bark scorpion” as part of their common name. If you’re in the United States of America and hear the term “bark scorpion”, however, it is very likely the speaker refers to one species in particular: the Arizona bark scorpion (C. exilicauda). This species earned its recognition by being the most venomous of the United States’ scorpions. The other species, lurking under rocks and in my nightmares, deliver a painful sting but are not considered deadly. (My own frenemy, the striped bark scorpion or C. vittatus, allegedly has a less painful sting than a honey bee. I don’t want to test that claim.)

These scorpions may be identified by their narrow pincers (or pedipalps) and tail. Their average size is around 60mm, and males tend to have a longer tail than females

Background on the Scorpion

In North America, various species of bark scorpion can be found across the southwestern part of the continent. Their range extends down into Central America and northern South America. For example, the specimen at the top, C. edwardsii, ranges from Mexico to Colombia. These scorpions are highly adaptable and may be found in deserts, forests, and grasslands. They hide in crevices, under rocks, or beneath tree bark, among many other places. Like my mailbox.

Like spiders, scorpions are arachnids. They don’t catch prey in a web, however. Instead they wait until their prey wanders by, feeling with the sensitive hairs on their pedipalps for the vibrations it creates. They ambush the animal—be it a spider, insect, or even a centipede—and sting it with the venom in the telson at the end of their tails. When the prey is paralyzed, they liquefy it with enzymes and slurp up what remains.

Party Facts about the Scorpion

Scorpions don’t get just one party fact. They get three because they are awesome animals.

1) Although bark scorpions are generally solitary, they occasionally congregate in large groups, particularly in winter. This makes for extra excitement when taking the trash out barefoot if they’ve chosen to congregate under the bin.

2) Scorpions are viviparous, meaning their offspring are born live. The offspring, averaging 30 in number, then crawl onto the female’s back. She carries and protects them until their first moult, which is when they climb down to fend for themselves. Although they live independently after leaving the female, immature scorpions have been observed climbing onto the backs of other adult female scorpions.

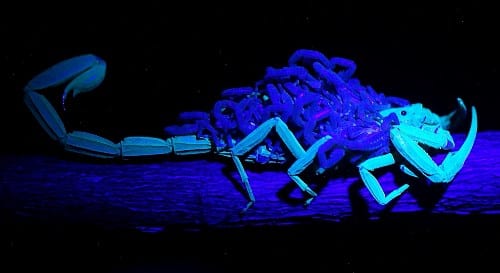

3) The scorpion is covered by a waxy cuticle that helps prevent water loss. This cuticle fluoresces a bright blue under UV light (but we don’t know why).

Beyond being an easy way to spot this nocturnal crawler at night (if you have a UV torch), the fluorescent capabilities of the scorpion have medical uses. Tumor Paint, derived from deathstalker scorpion (Leiurus quinquestriatus) of the Middle East and North Africa, is currently undergoing clinical trials. The molecules “stick” to the cancer tumour and fluoresce, allowing doctors to spot it more easily during surgery. (Okay, so the deathstalker isn’t a bark scorpion, but it’s still a scorpion and still cool.)

UV induced fluorescence of an adult scorpion and absence of fluorescence in juvenile scorpions (that are hanging onto mom).

(C) Frank.starmer, CC 4.0

And remember, if you ever visit scorpion country, shake out your clothes. You never know where one will pop up next.

References

Gouge, D. and Olson, C. (June 2011). Scorpions. Arizona Cooperative Extension.

Hurst, N. (19 October 2016). How Scorpion Venom is Helping Doctors Treat Cancer. Smithsonian Magazine.

San Diego Zoo. (2017). Scorpion. Animals and Plants.

Stafford, M. (November 2015). Arizona Bark Scorpion. U.S. National Park Service, Grand Canyon National Park.

Texas A&M University. (n.d.). Striped Bark Scorpion. Field Guide to Common Texas Insects.

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (February 2013). North American Centruroides (Bark Scorpion Venom). Toxicology Data Network.

Leah Christian is Front of House Volunteer in the Grant Museum of Zoology, and a UCL student of History and Philosophy of Science.

Close

Close