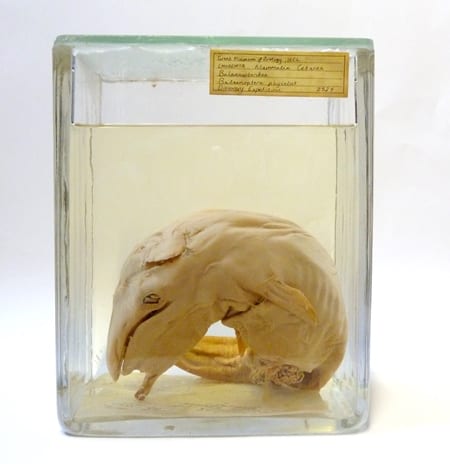

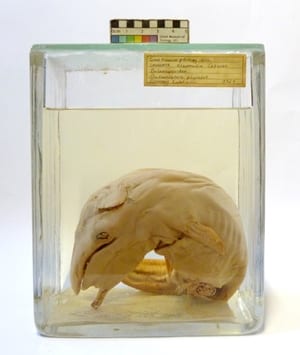

Specimen of the Week 210: the fin whale foetus

By Will J Richard, on 19 October 2015

Hello! Will Richard here, bringing you your weekly dose of specimen. And this time it’s a real giant. I did a quick calculation and the average fully-grown version is equal to 875 of me. That’s 10 more than the “maximum capacity” of a District line tube train, 10 and a half packed double-decker buses or 175 full cars. So in conclusion… it’s lucky that fin whales don’t commute. This week’s specimen is…

** the fin whale foetus**

1) Big baby

Just to make things clear this is not the world’s biggest jar. The foetus is much smaller than the adult (logically), measuring a mere 27cm. We know, therefore, that this is an immature individual within the early stages of development. The average gestation period for a fin whale is about a year and the calf is six metres long and weighs three and a half tonnes at birth – ours is nowhere near that. Calves feed every 10 minutes for the first six months but they never suckle. Huh? Instead, as they have no lips, the mother contracts muscles to force the milk into her baby’s mouth. Think syringe. Before weaning the calf will double in size, gaining kilogrammes an hour.

2) Fill up a fin whale (part one: the stomach)

Fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) are the second largest animals (probably ever) in the world, big females growing to 27 metres and weighing over 100 tonnes. Despite their size these whales do not hunt large prey, instead they use bristle covered sheets (called baleen plates) suspended from their upper jaw to filter the water of plankton, small fish, crustaceans and squid. They also take big gulps from schools of fish and it has been hypothesised that they present their bright underside to the panicking shoal as they circle: dazzling them, forcing them together and making them easier to catch. While feeding they can dive for 40 minutes at depths of over half a kilometre.

3) Fill up a fin whale (part two: the lungs)

Yes, they have enormous lungs but these are actually comparatively small for their body size (air sacks make diving difficult). Instead less is more, though it’s hard to think of a few thousand litres as “less”. Humans breathe shallowly, clearing approximately 15% of our lungs with each breath. Fin whales, on the other hand, with increased elastic fibres in their lungs’ lining push an estimated 90% of the air out with each exhalation before replacing this with “fresh”, more oxygenated air. They can also store more of the oxygen that they inhale (whales 75%, humans 36%) due primarily to an increased concentration of oxygen storing protein (myoglobin) in the muscle tissue.

Fin whale from above by Sabine’s Sunbird. Image in the public domain.

4) Wailing

Fin whales live in groups (pods) usually containing six or seven individuals and communicate through a wide range of vocalisations all of which, unfortunately, are out of our hearing range. They have a cruising speed of over 37 kilometres an hour and so a straggler can quickly be left behind and it’s very difficult to find a child, a parent or a partner in the open ocean. It is vital, therefore, that their calls carry far and wide which low frequencies do in water: whale song can be heard thousands of miles away from the singer. They use different calls depending on who they’re talking to and what they want to say and pods have been recorded conversing in a process known as counter-calling. It is thought that the whales can learn a lot about their surroundings by the way the sound travels between the groups.

5) Whaling

It is estimated that fin whale numbers dropped by over 70% between 1929 and 2007 mainly because of the mass harvesting that was commercial whaling. The “industry” reached its peak in the 1960s with more than 30,000 fin whales killed each year. It is very difficult to come across accurate figures for the total numbers of whales taken, though by adding up local estimates I came to a figure of 926,000. That means that nearly a million fin whales were killed in the first 75 years of the 20th century. It’s amazing there are any left really…

Whaling ship circa 1900 by Colporteur. Image in the public domain.

References:

Whitlow W.L. edited by Fay R. R., Popper A. N. (2000) Hearing by Whales and Dolphins; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

The IUCN red list of Threatened Species: Balaenoptera physalus

Will Richard is Visitor Services Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

Close

Close