Specimen of the Week: Week 166

By Mark Carnall, on 15 December 2014

Following on from last week’s focus on one of our specimens that will be receiving a spot of conservation TLC as part of our Bone Idols: Protecting Our Iconic skeletons conservation project, this week’s specimen is another specimen we’re looking to raise funds to conserve.

Following on from last week’s focus on one of our specimens that will be receiving a spot of conservation TLC as part of our Bone Idols: Protecting Our Iconic skeletons conservation project, this week’s specimen is another specimen we’re looking to raise funds to conserve.

This specimen is one of the largest* single specimens in the museum and sits in the heart of the displays. Although the specimen isn’t instantly recognisable, visitors I talk to about it are in reverance to it’s overall ‘bigness’ and after a few clues can identify what it is.

So pack your trunk and prepare never to forget this week’s specimen of the week which is…

**THE ASIAN ELEPHANT SKULL**

Image of the elephant skull LDUCZ-Z237 and LDUCZ-Z238 (the cranium and mandible are numbered seperately) as it is in the museum today

1) Heavy lifting. There’s little about an elephant’s anatomy that isn’t amazing from adaptations to deal with being a massive animal through to the well known but still strange trunk and of course the large ears which, according to at least one documentary, Dumbo, can be used for flight. What we have here with the business end of the animal is a skull that needs to support the massive weight of the teeth and tusks, which you can attest to if you’ve ever been to one of our events and felt the weight of a single elephant tooth. This is the skull of an Asian elephant, Elephas maximus distributed from Southeast Asia to Borneo. Currently there are thought to be three subspecies of Asian elephant all of which are endangered due to a lethal mix of poaching and widespread habitat destruction and loss.

2) A ‘Grant’ specimen If you are a regular reader of this blog you’ll know that a big challenge of being the curator of the Grant Museum is trying to recompile the history of the collection and individual specimens from our partial archive, scattered label information and the odd UCL meeting minutes and council reports. Frustratingly we know very little about the first 70 years of the collection until the first catalogue of the collection was produced in 1898 and critically, this unknown time covers the period when our founder Robert Edmond Grant started the collection. The only direct evidence we have of what was in the collection are two curious documents from 1850 which go to great pains to describe the system for denoting material that belonged to UCL and the material the belonged to Grant. The documents are meticulous about about how the specimens and the equipment were to be labelled (blue marks forUCL, red for Grant), ordered and stored together but the details on the specimens themselves are quite sketchy only listing vague ‘dried parts’ and ‘soft parts’ under each animal group. Under elephants “4 Skulls of Elephants/2 young 2 adults” are listed and it just so happens we have four near-complete elephant skulls in the collection and on display today, 2 of which are adults and 2 of which are young. It’s suggestive but not definitive proof that it’s the same elephant skull, but quite a few of the specimens listed in the 1850s document are no longer present in the collection.

3) History on open display As with a lot of our larger specimens, the size contraints means that many have been on open display (not protected in a display case) since they were acquired. A photo dating from 1930 when the museum was in the Medawar Building, shows this skull on open display, complete with the tusks in the skull in what looks like a rather precarious position, through our health and safety concious eyes, perched on top of the display cases with the tusks overhanging. Since then the tusks have been removed, probably for space saving and safety reasons. The elephant skull is still on open display today but the plan for the specimen as part of our conservation fund raising drive through the bone idols project is to encase the skull so that it is slightly buffered from environmental changes, the pollutants that coat the specimen from the heavy traffic and our visitors in addition to curious hands of our visitors.

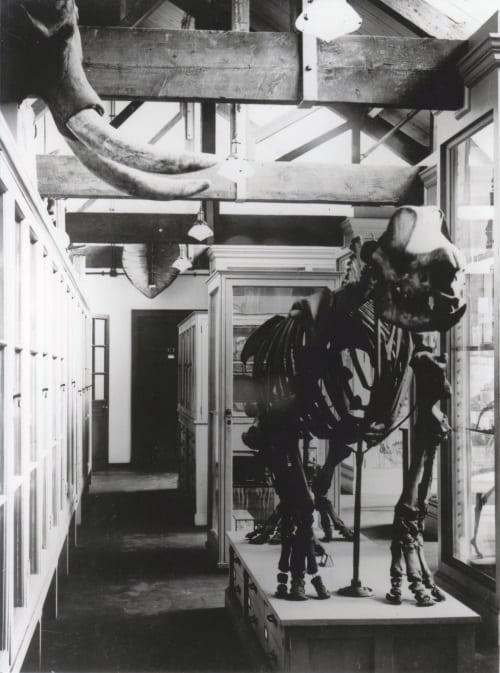

Image of the skull and tusks on display in the Museum in the Medawar Building in the 1930s alongside our rhino skeleton which is also part of the Bone Idols project.

4) Rain cap In between dangling over visitors in the Medawar and sitting in the heart of the museum today, the large skull was also on open display in the museum’s former premises in the Darwin Building at the end of one of the bays of display cases underneath on of the air conditioning units. Unfortunately, due to the air conditioning system being too small to deal with the size of the space, the issue that they were regularly clogged up with dust from Gower Street traffic and, as we found out during a refurbishment, the fact that the air conditioning units weren’t plumbed into anything, these units would regularly fail and either spray water or occassionally sooty hail over the skull. Because there was no other space to move the skull and it needs heavy lifting equipment to move, the only way of protecting the specimen from the air con units was with the use of a comedic rain hat (bin liners) we’d put over the specimen.

5) Conserving the Elephant. This elephant skull has likely been on open display for at least 164 years without protection from the environment and this has taken its toll on the specimen. In between being moved around campus over the years, evacuated during the second world war, no doubt handled and prodded by students, spat on by air conditioning units, coated in dust and pollutants, exposed to daylight and gas lamps it’s amazing that the specimen exists at all. This rather tramatic museum history of this specimen can be seen on the specimen today, there are stains, cracks, pits and sections of broken bone. The proposal for Bone Idols project is to clean and stabilise the specimen, buffering the robust but somewhat brutal way the skull is attached to the mount and to encase the specimen, keeping this historic specimen available to our visitors albeit in the hope that it will last another 164 years. It’s critical work that will safeguard our rarest and most significant specimens for the long term future. We still need to raise the funds to complete the project so please do support the project here.

Mark Carnall is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology

* As ever set the hyberbole detectors to maximum as we can quibble for hours about what largest, biggest, rarest and all the other extreme elements of our specimens actually means (see a previous blog post about the rarest skeleton in the world). This specimen is one of the largest single specimen in the museum in general terms of bulkiness that isn’t a whole skeleton, although it is a cranium and a mandible. There are others that are longer (whale baleen) and ones that would give it a run for it’s money in terms of weight (our Megaloceros skull and antlers for one) and indeed general pain-in-the-backsideness when it comes to having to move the thing as I have now done at least three times in my career here.

Close

Close