What remains to talk about? Human bodies on display

By Alice Stevenson, on 24 July 2014

I’ve recently returned from holiday in Cascais, near Lisbon in Portugal, which was for the most part a fairly relaxing break. For the most part. There was the small matter of a rather lengthy complaint furiously scribbled into a comments book at one particular museum we visited and my husband being subjected to an in-depth critique of ethical museum display practice – for several hours. So what got me so agitated? The display of three mummies: two Peruvian and one Egyptian in the Museu Aqueológico do Carmo, Lisbon.

The subject of human remains in museum displays has been picked over extensively in recent years (some might say ad nauseam) and in the UK several ethical guidelines exist (e.g. from the former Department of Media, Culture and Sport). It is an emotive topic, one that is frequently selected as the focus of graduate masters dissertations (there were in fact two independent requests for information about human remains from students awaiting my attention on my return to the museum). Yet after so much scholarly and media scrutiny are there still issues to disentangle or recognise?

My ire at the displays in Lisbon was because of a complete lack of contextual information for the ancient remains. The only substantial text panel in the room announced that the purpose of the gallery was “to evoke the memory of the two most emblematic presidents of the Associaçäo dos Arqueólogos Portugueses”. Two short biographies of these 19th-century dignitaries followed. We learn therefore about Portuguese colonial aspirations, but nothing about the culture of the ancient people silently staring out from their glass cases under the watchful gaze of an assembly of oil-painted portraits of the establishment.

Back home here in London there is a very different sort of approach to the exhibition of human bodies being presented to the public this summer. The British Museum’s cutting-edge Ancient Lives exposition foregrounds the ancient individual and what scientific studies can reveal about eight specific lives and deaths.

In Portugal then human remains are objects, vignettes to a colonial legacy that is at least apparent, if not explicated or problematised as such. In the British Museum, on the other hand, human remains are subjects, with the colonial history of acquisition and subsequent study out of focus. Nor is much said about the ancient meanings of mummies. In some sense therefore, both the displays in London and Lisbon tell us more about the production of modern, western knowledge and power structures, including the primacy of taxonomic classification and scientific endeavour, than anything about how ancient peoples might have understood or valued these bodies.

But are we even asking the right questions about such collections? The recent book Unwrapping Ancient Egypt by Christina Riggs suggests not. Riggs convincingly argues that the very practice of mummification was a transformative act that made the human body something other, something divine. Neither object, nor subject the mummy that is revealed in her masterful study is a complex cultural artefact, both in ancient and in modern times. She calls then on museums and Egyptology to be far more transparent and self-reflexive in the narratives they choose to embed displays of human remains in, ones that are sensitive to these multi-layered histories.

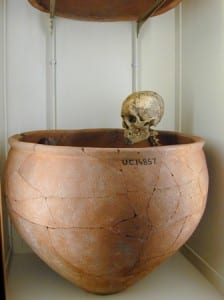

UC14856-58. A Badarian (4300-3900 BC) pot burial excavated by Ali Suefi in 1923 at Hememieh (North Spur burial 59) and first published by Guy Brunton and Gertrude Caton-Thompson in 1928.

The Petrie Museum itself looks after realtively few human remains (including body parts and hair) and no complete mummies (a full list is available here). Only one complete skeleton, from a prehistoric male burial, is presently visible in the gallery. The current text panel gives several histories from the ancient culture, the modern discovery of the burial in the 1920s and the scientific analysis of the 1960s. We also directly invite the viewer to think about the ethics of such display. This is just one approach, and I think there’s yet more we can do to address how such exhibits are presented, perceived and received. It is these processes of thinking, debating and critiquing that needs to be continuously returned to because there will always remain much to discuss as new contexts and historical conditions emerge.

One Response to “What remains to talk about? Human bodies on display”

- 1

Close

Close

Fabulous, what a web site it is! This blog provides valuable

data to us, keep it up.