Is it ever acceptable for museums to lie?

By Jack Ashby, on 16 April 2014

I ask this question to our Museum Studies Masters students every year, and last month put it to our new Bachelor of Arts and Sciences students. Despite the difference in the age, background and interests of these two groups, the reaction is the same – anger and horror. I am playing devil’s advocate in these debates, but my own opinion is yes, there are circumstances when everyone benefits from museums lying.

The lectures I discuss this in focus on object interpretation, and I use a tiger skull as a prop for discussing how to decide what information to include in labels. The choice of a tiger isn’t important – I just need something to use as an example I can attached real facts about natural history and conservation to, but I spend the two hours talking about tigers.

At the end of the lecture I reveal that the skull is in fact from a lion. Everything else I told them about tigers is true. Did it matter that I lied?

Lying about what objects are?

Museums surely can’t lie about an object’s identification, right? But if a museum didn’t have any tigers, is it reasonable that they can’t talk about tigers? Let’s say a museum was putting on an exhibition about Indian wildlife. It would be absurd to run that exhibition without a tiger*. Why not just use a lion skull and label it “tiger”?

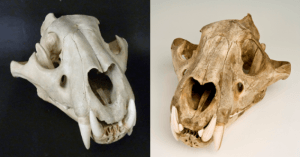

There are anatomical differences between tiger and lion skulls, but they are slight. Any normal visitor reading labels about tigers wouldn’t know the difference, or need to know. There is no question that a museum shouldn’t deceive an academic researcher studying the specimens, but in a display for the general public, could this lie be acceptable?

My students say that this calls into doubt everything they have been told – how can they trust anything? “Museums are supposed to repositories of knowledge” (however old fashioned you might think that notion to be).

Think of it another way. Some skulls in the Grant Museum are labelled gibbon, but we don’t know which species.

In an exhibition about Indian wildlife, would it be lying, or wrong, to use one of these gibbons to represent hoolock gibbons (an Indian species)? It probably isn’t a hoolock gibbon, but it doesn’t seem as wrong as the tiger vs. lion “lie”, does it? But it’s the same as if that skull was just identified as “big cat”.

The students say that you can still tell the facts about tigers, but at the bottom of the label say “this is actually a lion”. I think that would look very weird and confuse the visitor.

I asked this on Twitter and two responses said “If you need to lie about the object to tell the story, the story isn’t true.” I disagree.

Lying about where objects are from?

I’m not suggesting something like “This tiger was caught in Brixton” – that would be factually incorrect and misleading. What about an exhibition about British wildlife… About half the world’s grey seals breed in Britain, but what if a museum didn’t have any British grey seals?

Would it be acceptable to include a Danish grey seal? It’s the same species. How different is this to the lion/tiger above?

Both of these examples raise a question about what objects are really for in museums. People wouldn’t visit just to come and read labels without objects. The objects are the source of interest – people look at them, learn what they are (or what we tell them they are) and leave happy that they’ve seen them. They may read the text, but many wont.

It could be argued, then, that it doesn’t matter if they have seen the object; just that they think they have. This is the bottom a slippery, dangerous slope that makes me very uncomfortable, but I think the two questions above are often acceptable, and they are definitely on this spectrum of deceit.

Lying about whether objects are real?

The students I mentioned are genuinely gutted when I tell them that most of them have never seen a real large dinosaur skeleton. Dinosaur skeletons are heavy (fossils are made of stone), often incomplete and the demand out-strips the supply, so the same fossil replicas are displayed in more than one museum. Most museums use plaster casts of real dinosaurs, and most label them as such.

Nevertheless people are surprised when they are told they aren’t real (they don’t read the labels). The disappointment they feel might detract from both the awe and enjoyment they feel about them, and the facts they learn about them. Not to mention that some will doubt they ever existed in the first place.

Such distractions might tempt museums not to mention that the objects are replicas. Is this ever acceptable?

I used to say no, and certainly never when it came to handling objects, fossils or archaeology (“fake” artworks, I feel, are fraud of a different nature). But then I remembered there is a viper skull in the Grant we don’t bother to label as a cast, as it just doesn’t seem important. It’s a “Bone Clone” – a kind of cast that is essentially indistinguishable from the real thing in look and feel. We use it in teaching a lot, and people are amazed by this skull. Snake skulls are too fragile to handled, so this cast allows us to tell their fascinating story. Unless people ask, we don’t remember to tell them it isn’t real.

Somehow a common object like a viper feels different to a dinosaur skeleton, but deep down I know it isn’t.

Are any of these “lies” acceptable, or are there others you can think of? Let me know in the comments box.

Jack Ashby is the Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology.

*let’s assume they had been unsuccessful in trying to borrow one from elsewhere.

18 Responses to “Is it ever acceptable for museums to lie?”

- 1

-

3

Sam Barnett wrote on 16 April 2014:

I think there are times when a museum should lie but I don’t think the examples you gave fit that bill. If a member of the general public sees the sign indicating that a rhino horn is artificial, asks whether you have any real ones, and you do have some? By all means lie for the sake of the safety of the collection. If a member of the public has come to see your tiger, you’d better have a tiger. So what if the differences are slight? He might have seen a lion skull in the museum near home and gone out of his way to come and see your tiger to see if he can spot the differences. You have a duty to present the truth as it is presently understood. I don’t know enough about regional seal variation to assume – are the Danish and British seals near-identical? If they differ greatly you have to mention it. If they’re near-enough the same it still wouldn’t hurt to mention it. If they don’t read it, their not knowing is on them. Some of your visitors will read. Some of those will be Danish and be quite tickled that they came to England to see a Danish seal.

The cast vs real thing bugs me – always has. I appreciate casts need to be made but tell me I’m looking at the real thing or if I’m looking at a cast: when you know it’s real, it’s awe-inspiring to be near. You get the same feeling when you’re told it’s real and it’s not of course but the betrayal once you find out makes you less likely to believe that the next thing is real even if it is. The museum who cried wolf.

-

4

Nick Poole wrote on 16 April 2014:

Such an interesting question, and a very useful post. To me, what museums do is analogous to a kind of object-based journalism. In the same way that the whole integrity of journalism hinges on a professional code of ethics that is defined in a professional deontology, the trust which society places in museums hinges on our underlying ethics. In journalism, these ethics rest on balance and safeguards (such as checking sources and seeking corroboration). In museums, they depend on objectivity, research and the willingness to adapt to new knowledge – the idea that we always present our knowledge as fluid and subject to better evidence (in the same way as science in the Western rationalist tradition) is particularly important in this question of lying. If we deliberately falsify, or claim that something is an inalienable fact rather than an assertion, or rewrite provenance to increase value or promote propaganda, this is a direct abuse of the fundamental role of our sector. It is interesting that, unlike doctors or journalists, the professional deontology of museums is usually informal (there’s no Hippocratic oath for museum professionals) and yet, despite resting on an honour system, most of the time it seems to work!

-

5

Elizabeth Jones wrote on 16 April 2014:

I have encountered this issue in other museums. I like that you address this topic! There is certainly a tension between the whole truth for education and the part truth for entertainment. Do you avoid discussion of the giant ground sloth fossils in the basement collections just in case it were to expose museum visitors to the reality that much of the giant ground sloth on the exhibition floor is a reconstruction? Do you want education? Or entertainment? What is the point? And more importantly, can a museum uphold multiple objectives (education and entertainment) and make exceptions with “lies” in different instances?

-

7

Ian wrote on 16 April 2014:

I wonder how many people realise that the huge dinosaur skeleton in the main foyer of the Natural History Museum is not a genuine fossil, but a cast made from several then assembled to form one final animal display, and if they care.

-

8

Alexander Borchard wrote on 16 April 2014:

Thanks for sharing your interesting thoughts Jack. Lying about an object to get a story across strikes me as really strange and not just morally. Do you assume that visitors will only pick up the ‘facts’ the label offers? In that case, lying won’t matter much, maybe. But people construct knowledge against the backdrop of their past and future experiences, and it’s the future experiences where lying about an object becomes particularly problematic. Imagine one of these only slight anatomical differences between lion and tiger skull as the centre of a future learning experience. It would be (and maybe not just ‘slightly’ anymore) faulty and outside the control of the museum that lied about it.

-

10

Erika wrote on 18 April 2014:

Completely unethical and not excused by hiding behind the short labels excuse. By using that excuse you are essentially saying that visual design and look of an exhibition is more important than truth. When museums start crossing that line as standard I’m out, I’ll change careers.

-

11

Museums, Politics and Power | Weekly News Roundup: April 21, 2014 wrote on 21 April 2014:

[…] Is it ever acceptable for museums to lie? […]

-

12

Paul I wrote on 9 May 2014:

“The students say that you can still tell the facts about tigers, but at the bottom of the label say ‘this is actually a lion’. I think that would look very weird and confuse the visitor.”

Interesting post! I think your problem isn’t an ethical issue, it’s a copywriting issue.

I think it’s fairly obvious that you shouldn’t lie at a museum. You shouldn’t present x as y, even if x is really, really like y. And if a dinosaur bone is actually a plaster cast? Disappoint the kids and label it as such.

The problem is: you’ve got to find someone who’s really, really good at writing labels. There’s no reason the truth shouldn’t be as interesting as a lie, if it’s written well enough.

-

13

Mark Carnall wrote on 9 May 2014:

Paul, your last paragraph really struck a chord with me. Particularly with many museums ‘boasting’ about the collections they don’t display it seems counter-intuitive to have to fudge interpretation to say something interesting.

Personally, I find having to be creative about using specimens which aren’t of obvious interest or even using specimens which aren’t obvious themselves can be more interesting than the objects and interpretations you’d expect to see.

-

14

Paul I wrote on 9 May 2014:

Yes – agreed. And the given the fantastic Grant Museum blogs, it’s clear you don’t want for good copy writers.

-

15

Mary wrote on 8 January 2015:

I call out the “science” museum for all their Global Warming/Climate Change/Whatever it is today non-science hype.

-

16

Handling Collection: Origin | Wellcome Collection Blog wrote on 7 July 2015:

[…] question about the significance of using “real” objects versus replicas in museums is often raised. Clearly, there is a wow factor and an emotional effect with genuine objects, but this does not […]

-

17

Specimen of the Week 204: The ringtail skeleton and tail skin | UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 7 September 2015:

[…] Our ringtail skeleton is unique in the Grant Museum (as far as I have noticed) in that it still has its penis bone mounted. Most mammals have bones in their penises – including primates (but not humans), rodents, moles, shrews, hedgehogs, carnivorans (including ringtails) and bats. There’s a really handy acronym to remember that but it’s borderline sweary, so maybe tweet me if you’re super keen. However, Victorian (and later) prudishness resulted in the vast majority of these bones – and their clitoris counterparts – being removed from museum displays and hidden in drawers. Yet more evidence that museums lie all the time. […]

-

18

Do some animals look too boring to be in a museum? | UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 22 March 2016:

[…] all options require us to tell the truth is, of course, a […]

Close

Close

If museums simply exist as you say, for “people [to] look at them, learn what they are (or what we tell them they are) and leave happy that they’ve seen them,” then they are an anachronism; a Victorian freak side-show. If they exist to educate and as “repositories of knowledge” then you must tell the truth, even if it appears only in small sub-text. Not only is that the morally correct thing to do, but surely those were actually the most interesting facts about the examples you have given – that Tigers and Lions skulls are practically indistinguishable, that snake skulls are too fragile and replicas must be used, that the plaster casts of Dinosaurs are usually incorrect because they were made a Century ago. Do what you must do, but explain why you need to do that. Educate your audience rather than patronizing their ignorance.