On the Origin of Our Specimens: The Minchin Years

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 6 March 2014

The collection of specimens, known since 1997 as the Grant Museum of Zoology, was started in 1827 by Robert E. Grant. Grant was the first professor of zoology at UCL when it opened, then called the University of London, and he stayed in post until his death in 1874. The collections have seen a total of 13 academics in the lineage of collections care throughout the 187 year history of the Grant Museum, from Robert E. Grant himself, through to our current Curator Mark Carnall.

Both Grant and many of his successors have expanded the collections according to their own interests, which makes for a fascinating historical account of the development of the Museums’ collections. This mini-series will look at each of The Thirteen in turn, starting with Grant himself, and giving examples where possible, of specimens that can be traced back to their time at UCL. Previous editions can be found here.

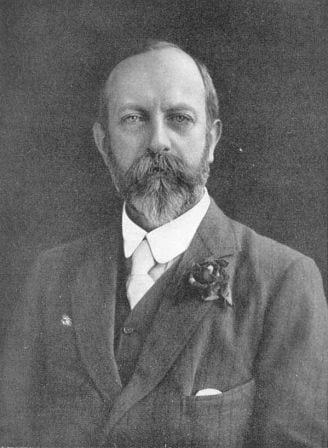

Number Five: Edward Alfred Minchin (1899-1906)

Number Five: Edward Alfred Minchin (1899-1906)

Born in 1866, Minchin was plagued from an early age with a debilitating medical condition. Although information regarding the nature of the condition can not be located, it is known that it left Minchin with physical disabilities. According to those that knew him however, whatever disabilities Minchin may have faced, he did not let them deter him from the pursuit of his goals. Minchin received a private education, as seems to be the way of The Grant Museum Curator (thus far). In 1880, at the age of 14 Minchin moved to India where his parents had been living, and continued his education there. After a few years, he returned to the UK to study zoology at the University of Oxford, and graduated in 1890 with a first class degree. He became the assistant to E. Ray Lankester, another previous curator at the Grant Museum, and demonstrated comparative anatomy at Oxford from the time of his graduation up until 1899.

In 1899, the most important chapter of Minchin’s life began as he took over from our third curator, Professor Weldon, and became the fourth successor to Grant as curator of the Grant Museum at UCL*. Along with the care of the collections, Minchin was appointed Chair of Zoology, which he held until he was elected Chair of Protozoology in 1906, also at UCL*, which he remained until his death.

In 1899, the most important chapter of Minchin’s life began as he took over from our third curator, Professor Weldon, and became the fourth successor to Grant as curator of the Grant Museum at UCL*. Along with the care of the collections, Minchin was appointed Chair of Zoology, which he held until he was elected Chair of Protozoology in 1906, also at UCL*, which he remained until his death.

Minchin published on a number of invertebrate groups but his research centred on Protozoa and Metazoa with particular attention paid to the anatomy, histology, development, and classification of calcareous sponges. He worked in labs throughout Europe, including Croatia, Naples and France, and was well known in his field.

In 1905, Minchin joined the Commission of the Tropical Diseases Committee of the Royal Society on a research trip to Uganda to investigate the relationship of the tsetse-fly to sleeping sickness. Aside from the main aim of the field trip, the research also concluded that the tsetse fly carries a number of other ‘wild’ trypanosomes. trypanosomes are parasites transmitted by insects, that pertain to the genus Trypanosoma. After Minchin returned to the UK, his research began to focus on trypanosomes, leading him to discover and formally describe the various stages of his Ugandan specimens, before going on to study trypanosomes in fish and then rat fleas.

Minchin wrote his last works up to deliver in an address to the meeting of the British Association held in Manchester in 1915. Sadly, a deterioration in his health prevented him from delivering the address in person, and led not four weeks thereafter, to his death.

Minchin wrote his last works up to deliver in an address to the meeting of the British Association held in Manchester in 1915. Sadly, a deterioration in his health prevented him from delivering the address in person, and led not four weeks thereafter, to his death.

It seems that it was the way of earlier Grant Museum curators to not label specimens brought in to the museum through their own research, with their name. Perhaps this was because the collections were a teaching collection only during the 1880s and early 1900s, meaning that paperwork, as mentioned in the introduction, was not so strictly required. It seems unlikely, that these eminent researchers did not acquire any of their research specimens in to the collections.

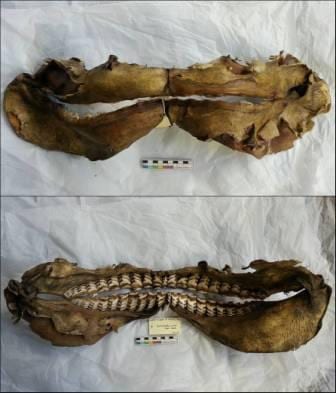

There is some evidence to suggest that a number of specimens in the collections today were, not collected by Minchin, but most likely acquired for the collections by him. One such specimen is the articulated jaws of a tiger shark (image to the left). The scan of the paperwork shown above, refers to Grant Museum acquisitions from 1891 to [unspecified]. The list contains the specimen ‘1534 Galeocerdo jaws. Stock”‘. Based on the curatorial nature of the document and the date of the section illustrated above (1900-1901), this is presumably Minchin’s own handwriting.

There is some evidence to suggest that a number of specimens in the collections today were, not collected by Minchin, but most likely acquired for the collections by him. One such specimen is the articulated jaws of a tiger shark (image to the left). The scan of the paperwork shown above, refers to Grant Museum acquisitions from 1891 to [unspecified]. The list contains the specimen ‘1534 Galeocerdo jaws. Stock”‘. Based on the curatorial nature of the document and the date of the section illustrated above (1900-1901), this is presumably Minchin’s own handwriting.

*Then called the University of London

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Curatorial Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

[UPDATE: Whilst researching this blog series, it was discovered that there had been an extra curator for a few months, following Roy Mahoney. As such, The Twelve became The Thirteen. As the aim of this series is to serve as a permanent record of our history, this and all subsequent blogs have been updated to reflect this exciting discovery.]

Close

Close