On the Origin of Our Specimens: The Allchin Years

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 13 February 2014

The collection of specimens, known since 1997 as the Grant Museum of Zoology, was started in 1827 by Robert E. Grant. Grant was the first professor of zoology at UCL when it opened, then called the University of London, and he stayed in post until his death in 1874. The collections have seen a total of 13 academics in the lineage of collections care throughout the 187 year history of the Grant Museum, from Robert E. Grant himself, through to our current Curator Mark Carnall.

Both Grant and many of his successors have expanded the collections according to their own interests, which makes for a fascinating historical account of the development of the Museums’ collections. This mini-series will look at each of The Thirteen in turn, starting with Grant himself, and giving examples where possible, of specimens that can be traced back to their time at UCL. Previous editions can be found here.

Number Two: William Henry Allchin (1874-1875)

Number Two: William Henry Allchin (1874-1875)

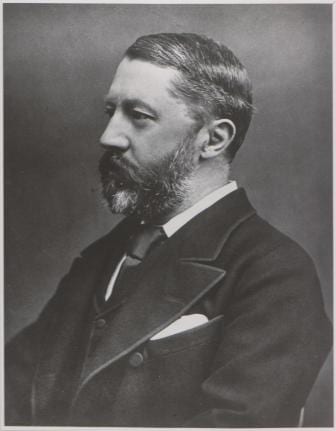

Despite the title of this edition of the mini-series, it would be more appropriate to say The Allchin Year. Sir William Henry Allchin was the first successor of Grant, but had the shortest time of The Thirteen at the reigns. He took over the collections in 1874 as Professor ad interim when Grant passed away still in post. Allchin was only at UCL for a year before E. Ray Lankester was appointed Chair of Zoology in 1875. Presumably Allchin did not remain as comparative anatomy was not his field of expertise.

Allchin was a Parisian, born in 1846. He was privately educated like Grant had been, before going on to study medicine here at UCL. He used his medical degree to join the SS Great Eastern (pictured below) as the medical officer. Allchin served in a number of medical roles before going full circle and coming back to UCL following Grant’s death. During the 1870s he worked at Westminster Hospital, first as registrar and demonstrator of practical physiology, before working his way through Assistant Physician to Physician in 1877. Allchin lectured on pathology, physiology and medicine, and held the office of Dean from 1878 to 1883, and again from 1890 to 1893.

Allchin had close ties with the Royal College of Physicians throughout his professional career and in 1883 was elected Assistant Registrar. After only two years in post however, Allchin resigned due to his opposing with the Royal College’s policy of only granting medical degrees once permission had been obtained from the Crown. Allchin has many accolades under his belt, not least of which is his position as editor at the well known journal A Manual of Medicine from 1900 to 1903. He had a distinguished career as a physician and medical administrator and was reportedly instrumental in the discussions leading to the University of London Acts 1898 and 1905. He retired from Westminster Hospital in 1905, before being knighted in 1907. In my personal opinion, second only to his one year stint as Chair of Zoology at UCL, Allchin’s most exciting moment was yet to come. After his knighthood, Allchin was appointed physician extraordinary (personal physician) to His Majesty King George V. After a long and prosperous career, Allchin passed away at his home on 8th February 1912.

Allchin had close ties with the Royal College of Physicians throughout his professional career and in 1883 was elected Assistant Registrar. After only two years in post however, Allchin resigned due to his opposing with the Royal College’s policy of only granting medical degrees once permission had been obtained from the Crown. Allchin has many accolades under his belt, not least of which is his position as editor at the well known journal A Manual of Medicine from 1900 to 1903. He had a distinguished career as a physician and medical administrator and was reportedly instrumental in the discussions leading to the University of London Acts 1898 and 1905. He retired from Westminster Hospital in 1905, before being knighted in 1907. In my personal opinion, second only to his one year stint as Chair of Zoology at UCL, Allchin’s most exciting moment was yet to come. After his knighthood, Allchin was appointed physician extraordinary (personal physician) to His Majesty King George V. After a long and prosperous career, Allchin passed away at his home on 8th February 1912.

As Allchin was only in post for a year, he did not have much of an opportunity to make additions or changes to the collections. If he did acquire new specimens, there is no trace of evidence to suggest as such. As zoology was not his area, and given the last minute nature of his assignment, it is probable that Allchin focused more on covering Grant’s lectures, than concentrating on the zootomical museum, as Grant referred to it in the 1800s.

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Curatorial Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

[UPDATE: Whilst researching this blog series, it was discovered that there had been an extra curator for a few months, following Roy Mahoney. As such, The Twelve became The Thirteen. As the aim of this series is to serve as a permanent record of our history, this and all subsequent blogs have been updated to reflect this exciting discovery.]

One Response to “On the Origin of Our Specimens: The Allchin Years”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] finally became the second successor to Grant, taking over the role of chair of zoology from Sir Henry Allchin in 1875. D.M.S. Watson, after whom our science library at UCL is named, later wrote the following […]