Specimen of the Week: Week Forty-Five

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 20 August 2012

Whilst looking for a sponge in the coral case, I came across something far more stupendous than both irritatingly-hard-to-tell-apart-at-times-I’m-not-really-an-idiot-I-swear-groups (ok I was having a dense moment). Although a few specimens of this species grace shelf two of case six (for when you are sure to pop in for some Specimen of the Week reconnaissance), this particular specimen is especially beautiful. You’ll think you know these animals well, but this specific genus exhibits a dollop of uniqueness, within the tentacled family tree. This week’s specimen of the week is..

Whilst looking for a sponge in the coral case, I came across something far more stupendous than both irritatingly-hard-to-tell-apart-at-times-I’m-not-really-an-idiot-I-swear-groups (ok I was having a dense moment). Although a few specimens of this species grace shelf two of case six (for when you are sure to pop in for some Specimen of the Week reconnaissance), this particular specimen is especially beautiful. You’ll think you know these animals well, but this specific genus exhibits a dollop of uniqueness, within the tentacled family tree. This week’s specimen of the week is..

**!!The Argonaut!!**

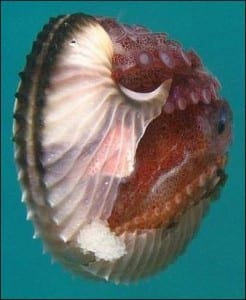

1) Is it a really thin water snail? Is it a knobbly-shelled nautilus? Is it the last known ammonite on earth in some weird mass-extinction defying twist of invertebrate good fortune? Nope. Please let me introduce you to the argonaut octopus. A cosmopolitan and euryhaline species (i.e. it lives everywhere, and anywhere), the argonaut is unlike any other octopus. If Jason’s argonauts were of this eight-tentacled variety, battling stop-motion skeletons would have gone a lot easier as they’d likely give up and sit down to marvel at the sheer wonder of Jason’s back-bone lacking crew. For argonauts, true argonauts, are really quite incredible creatures. For starters the group, Argonautidae, is defined by the ability of the females to secrete a shell, made of calcium carbonate, from distal webs present on their first pair of arms. Say what? Yep- an octopus that manufactures a shell, just like a snail.

2) The rather attractive shell is narrow and covered by two rows of large knobbly bits. The purpose of this taxonomy-terrorising shell is to protect developing eggs. As such, it is only the female that has one. She will motor around with her webs sprawled on the outside of the shell for grip, and is even also able to get inside it for protection, at times when she has no eggs to consider.

3) The eggs in each individual cluster are joined by a stalk, and attached to the shell in the order in which they were laid. Unlike most other octopuses, female argonauts survive reproduction and can thus also produce further generations. By the way, whilst the females emerge from reproducing with a) her life (unusually) and b) a lovely looking shell ornament, the male has a bit more of a rough time. After mating the tentacle that carries the sperm, basically its penis, will break off and stay in the female. Yowsers.

4) Males tend to be no longer than several centimetres whilst the frankly much cooler females can be up to two metres in length. Much to the hair pulling of marine biologists, a live male argonaut has never been observed in the wild making wild behaviour of these creatures particularly tricky to study.

5) Not content with making their own shells to play hide and seek in, argonauts in the Phillipine archipelago attach themselves to some species of jellyfish. This would be ok if the pair were good symbiotic friends but the octopus uses its arms to grip the jellyfish so tightly that many exhibit extreme damage as a result. Some jellies have even been seen with parts missing and bite marks that fit the beak of the Argonaut suspiciously well.

You get a sixth fact today because argonauts are just so fantastic…

6) To put off would-be predators, argonauts use both inking and countershading. Even if you haven’t seen Finding Nemo, inking is fairly self-explanatory. The octopus shoots out five or more dark grey blobs of viscous ink where they slowly elongate in the water. Each blob is called a pseudomorph, i.e. a physical ‘being’ that represents the octopus well enough to confuse the predator whilst the real argonaut jets off giggling at its own cunning. Counter-shading also has a fairly obvious explanation but to save you the job of thinking on a Monday morning- they ‘blend in’. Argonauts are darker on their dorsal surface to match the ocean depths to evade predators looking downwards, but reflective silver on their ventral surface for predators looking up at the bright sky (that probably only works for non-English ones). However like other octopuses, Argonauts can also change their colouring at will.

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Museum Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

One Response to “Specimen of the Week: Week Forty-Five”

- 1

Close

Close

That was a great read, I love the way you write. The argonaut sounds like a fascinating animal… although I sense some primitive examples of feminism were at play when evolution shaped this species! Thanks for the post (especially the Finding Nemo reference, nothing else cranks up the nostalgia factor quite as much), it was very inspirational to an aspiring naturalist like me, especially as I write a regular natural science column in my school paper.