Charlotte Rolfe, dressmaker – “So fair is the earth, both by night and by day!”

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 14 February 2020

Charlotte Rolfe, or Lottie, was the youngest daughter of Charles Rolfe, a tailor, and his wife Maria Rolfe. She was born in Bury St. Edmunds on the 2nd of February, 1856. There is no suggestion on the census returns that she was deaf until the 1901 census, so we may assume she had a form of progressive hearing loss, though it rendered her almost completely deaf. At earlier stages of life she was a servant, but later worked as a dressmaker. There were a lot of Rolfes in Suffolk, so they can be confusing, but I am sure of my identification of the right Charlotte Rolfe.

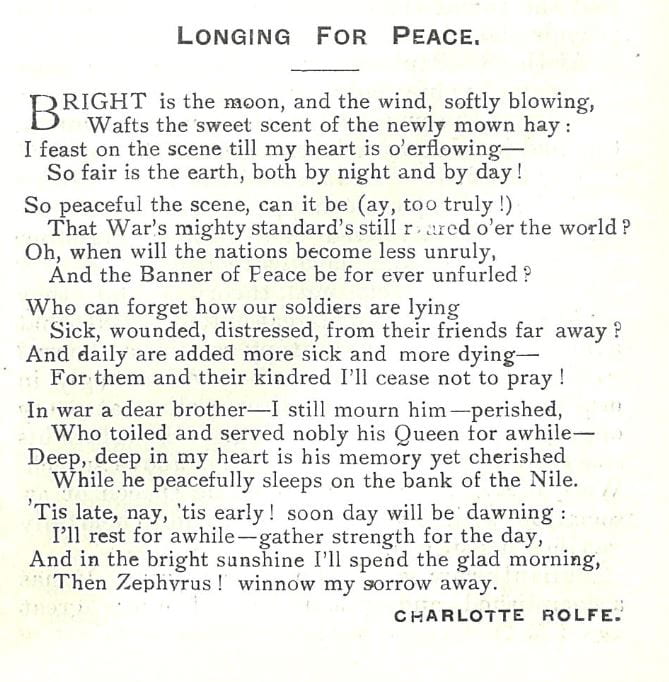

I came across her in the British Deaf Monthly (BDM), where she wrote what might be considered an anti-war poem –

LONGING FOR PEACE.

BRIGHT is the moon, and the wind, softly blowing,Wafts the sweet scent of the newly mown hay :

I feast on the scene till my heart is o’erflowing—

So fair is the earth, both by night and by day!

So peaceful the scene, can it be (ay, too truly !)

That War’s mighty standard’s still reared o’er the world ?

Oh, when will the nations become less unruly,

And the Banner of Peace be for ever unfurled ?

Who can forget how our soldiers are lying

Sick, wounded, distressed, from their friends far away ?

And daily are added more sick and more dying—

For them and their kindred I’ll cease not to pray !

In war a dear brother—I still mourn him—perished,

Who toiled and served nobly his Queen for awhile—

Deep, deep in my heart is his memory yet cherished

While he peacefully sleeps on the bank of the Nile.

‘Tis late, nay, ’tis early ! soon day will be dawning :

I’ll rest for awhile—gather strength for the day,

And in the bright sunshine I’ll spend the glad morning,

Then Zephyrus ! winnow my sorrow away.

CHARLOTTE ROLFE

I think that is a very good amateur poem. That she submitted a poem to the editors, suggests that she was familiar with the BDM, and felt herself a part of the larger deaf community.

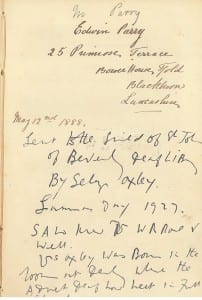

I take it her brother had died a few years before, perhaps serving under Kitchener, but I have not identified him – her parents had a lot of children and I have only a limited time to research this. I then found nothing more, until, that is, I looked in the British Newspaper Archive. That turned up another sad story, this time concerning Charlotte’s sister. I think the writer or printer added an incorrect age for her sister, who was I think 47 rather than 57. *

This story appears in the Hackney and Kingsland Gazette, for Wednesday the 9th of September, 1903 –

HOMERTON WOMAN’S SUICIDE

A SAD STORY

An inquest was held the Hackney Coroner’s Court Monday morning on the body of Mary Ann Dennison. 57, the wife of John Dennison, a silver finisher, of 31. Church-road. Homerton, who died from the effects of oxalic acid poisoning.

The husband of the deceased said his wife had no trouble of which was aware. When he left home on Friday morning she appeared all right, but returning the evening he found the room in darkness. He struck a light and then saw his wife lying dead on the sofa – dressed, with the exception of boots and stockings. On a chair near was a bottle and beside it a bill in which the bottle had evidently been wrapped by the chemist. Curiously enough, however, the name of the chemist had bean cut out. On the back of the bill the following note had been written to deceased’s sister, Miss Charlotte Rolfe, of Kentish Town : –

“Dear Lottie, – My head has been bad for years, and then I say and do foolish things. Poor old Jack is not to blame; he has been goodness itself to me! I can’t do so — l am best out of the way. God will call for my dearest of children! Don’t let them know I have taken my own life. – Tiny.” Tiny, explained the witness, was the name by which his wife was familiarly known.

The Coroner: The jury will naturally ask, “Why did she take her life?” What reason can yea give for that ?

Witness; Well, sir, I can only say I have found her come home now and again the worse for drink. And that upset her mind ?- I don’t know, sir, but I have seen her reeling now and again.

How often ? Pretty often, lately, sir.

Once a week ? -Once a day, sir, and been going for years on and off.

During that time she has threatened to take her life several times ? -Yes, sir.

What reason did she give ? -She said she was tired. I always asked her what she meant by it, and I never could get anything out of her.

Charlotte Rolfe, to whom the note was addressed, said she last saw her sister on Friday week, when she made the curious remark that a number of people had committed suicide lately. This witness was so deaf that the Coroner had write down the questions he wished her to answer.

Dr. J. C. Baggs said he found the bottle referred to contained a small quantity of oxalic acid. Deceased’s mouth was burned by some corrosive poison, and death was due to oxalic acid poisoning.

A verdict of Suicide whilst temporally insane was returned.

Mary Ann clearly had a form of depression of long standing, and was unable to articulate it, even to her family.

She was retired at the time of the 1939 register, and living at The Sycamores, Beck Row, Mildenhall. Her death was registered in Birmingham – perhaps she was visiting family or friends – noted in the Suffolk paper The Bury Free Press,

ROLFE.—On January Ist. 1945, CHARLOTTE ROLFE passed peacefully away, aged 89 years. Service at St. Marylebone Crematorium. North London, Jan. 22nd.

but she was cremated in London.

If you discover more about Charlotte, please do contribute in the comments field below.

* NOTE: Thanks as ever to Norma Mcgilp who found her in the 1939 Register, and when she died.

Also, apologies but I somehow lost the ends of two sentences in this version, now corrected.

1861 Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 1141; Folio: 142; Page: 22; GSU roll: 542762

1871 Census – Class: RG10; Piece: 14; Folio: 7; Page: 8; GSU roll: 838752

1881 Census – Class: RG11; Piece: 863; Folio: 73; Page: 42; GSU roll: 1341204

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 1451; Folio: 152; Page: 30; GSU roll: 6096561

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 204; Folio: 10; Page: 11

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 9881; Schedule Number: 76

BDM vol: 9, no. 107, September 1900 p.245

Close

Close