Three Deaf Ladies of Liverpool, “respected and loved by all who know them”

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 26 June 2018

In The British Deaf Times for January-February 1921 has this charming picture of three deaf ladies. The paper of this issue, and some from late in the war, was acidic in quality, and has deteriorated seriously in the last few years as it has been well-thumbed by users. This volume really needs restoration – that involves sandwiching those pages within some opaque material, but that makes pages less clear. An ideal solution would be proper digitisation.

All three were “deaf and dumb, and have been from birth.” The lady in the centre is Miss Mary.E.Walker (her initials were M.A.E. or perhaps M.E.A.). She was born on January the 1st 1836 in Leeds. The article tells us she was deaf from birth, but the censuses omit that information. She was a ‘lady visitor to the deaf,’ by which we must suppose she worked with local missioners, visited Deaf people in her community, and presumably prayed with them. I suppose it was a sort of community support worker role. At any rate, she did that for thirty-five years, presumably able to support herself ‘by her own means’ as the census says, having a wealthy family background.

Margaret C. Hawkins on the left, was born in 1841. She died in 1923. She was also a ‘lady visitor,’ connected to the Liverpool Society. In the 1881 census, where she is recorded as deaf and dumb, she was a teacher, living at a convalescent home for children at Black Moss Lane, Maghull, Lancashire.

On the right, Miss Mary Housman was born in Liverpool in January 1844. By 1901 she was living with Margaret in 76 Rosebery Street, Toxteth. Looking at it on Street-view now shows that it is long gone. It would once have been neat back-to-back housing, and their neighbours in 1901 were in occupations such as clerks, chemists, a police sargeant, and a stevedore, whereas most of the housing left is run-down, and the remaining terrace of once pretty houses looks as if it is condemned. Interestingly, the two ladies, both described as ‘deaf and dumb from childhood,’ had two other Deaf lodgers, Robert Fletcher Housman (1846-1921) who was her brother, and Anne (Annie) Jackson, b.1844. The Housman family was from Skerton,Lancashire, their parents, Robert Fletcher and Agnes were ‘landed proprietors.’ Robert junior was described as deaf in the 1861 census but his sister as deaf and dumb.

Anne Jackson was born in Lichfield, Staffordshire. She was a servant working for Housman and Hawkins in 1891, but by 1911 is described as living with them under her own means. In 1891 they were in 24 Jermyn Street, which is not too far from their later home in Rosebery Street. Margaret Hawkins was described as a ‘lady Visitor’ which the enumerator has misunderstood as meaning she was not head of the household, and ‘Deaf and dumb from birth.’ The other members of the household are described as ‘Deaf and dumb.’ As well as Mary Housman as a boarder and the servant Annie Jackson, there was also an Eliza Jane Hudson, b.1852 in Carnarvon, as a boarder, and Mary Rigby, b.ca.1840 in Liverpool.

In 1871 Rigby was living with her widowed mother, in Slater Street. She was ‘Deaf from Fever’ which explains why she was not marked as deaf on earlier censuses.

By 1911 the three were living together at 14 Hatherley Street, Liverpool, the next street down from Rosebery Street. A certain P.H. Morris, b.ca. 1874, in St. Helen’s, ‘Deaf from born,’ is there as a boarder. I tried looking for a female P.H. Morris to no avail, but there is a Philip Hornby Morris who was born in the right place and was the right age to fit. As the age column has been altered – the usual 1911 census error where people did not read the form before filling it in – I wonder if our deaf P.H. Morris is him… I am open to correction!

In 1921 when the article was written, they lived together at Prenton, Birkenhead, all three being, we are told, ‘staunch churchwomen.’ The were, we are assured, “respected and loved by all who know them.” They were part of a network of Deaf people, and we might assume there were other boarders and visitors from the Deaf community in the north west in the intervening years not covered by the censuses. It would make an interesting project to follow the lives of all these peoplewith some sort of social network analysis.

An Appreciation. The British Deaf Times 1921 p.8

Miss Walker

1841 Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 1346; Book: 4; Civil Parish: Leeds; County: Yorkshire; Enumeration District: 4; Folio: 26; Page: 2; Line: 10; GSU roll: 464289

1861 Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 3357; Folio: 123; Page: 31; GSU roll: 543119 – Headingly with her sister Elizabeth

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 3463; Folio: 39; Page: 2 – Poulton Bare and Torrisholme, Lancs. as a visitor in a lodging house.

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 4914; Folio: 78; Page: 21

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 22266

Miss Housman

1851 Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 2272; Folio: 106; Page: 56; GSU roll: 87299

1861 Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 3156; Folio: 62; Page: 21; GSU roll: 543088

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 2936; Folio: 54; Page: 41

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 3438; Folio: 41; Page: 21

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 22266

Miss Hawkins

1881 Census – Class: RG11; Piece: 3744; Folio: 99; Page: 10; GSU roll: 1341896

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 2936; Folio: 54; Page: 41

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 3438; Folio: 41; Page: 21

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 22266

Miss Rigby

1871 Census – Class: RG10; Piece: 3775; Folio: 46; Page: 33; GSU roll: 841888

1881 Census – Class: RG11; Piece: 3651; Folio: 39; Page: 17; GSU roll: 1341875

Close

Close

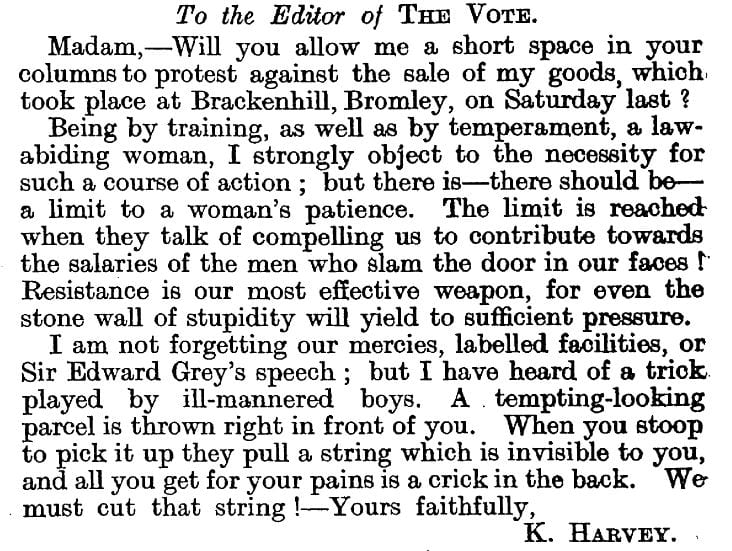

Article from The Vote, June the 17th, 1911

Article from The Vote, June the 17th, 1911