“so moved by these unhappy souls” – Tommaso Pendola, Italian Teacher of the Deaf

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 6 November 2015

This article was written by our colleague Debora Marletta, with some additions.

Born in Genoa on the 22nd of June 1800, Tommaso Pendola (1800-83) joined the order of the ‘Scolopi’, the Piarists (Order of Poor Clerics Regular of the Mother of God of the Pious Schools) at the age of 16. In 1821 he began to teach at the Collegio Tolomei in Sienna. The following quotation is phrased in a way that will sound familiar to regular readers –

Having found several deaf-mutes in Sienna, his city of adoption, he was so moved by these unhappy souls, shut out from the consolation of speech, and so desirous of relieving them from their melancholy condition, that, in 1825, he went to Genoa and placed himself, for nearly a year, as a youthful scholar under Padre Ottavio Assarotti, of the Scolopian Order, who, like De l’Epée in France, was another father to the deaf in Italy. Having learned the method well, Padre Pendola spent all his means in providing a refuge for these unfortunate ones and instructing them. (Matson, p.214-5)

L’Abate Ottavio Giovan Battista Assarotti (1753-1859) had founded the first deaf school in Italy, at Genoa, in 1801.

In 1831, under the auspices of the Grand Duke Leopoldo, Pendola founded and directed in Sienna an institute dedicated to the education of poor deaf people, later known as the Istituto Tommaso Pendola and now part of Asp (Azienda Pubblica dei Servizi alla Persona) ‘Città di Siena’. In 1844 it was united with the school at Pisa.

Exulting in his heart, happy in relieving misery, he was the first among us to give a gentle and pious mother to these afflicted ones, calling to his Institution “The Daughters of Charity,” and when, in 1848, the members of this order were driven from Sienna as by a whirlwind, those of them that were with him remained peacefully under the protection of his uncontested authority. (Matson, p.215)

As Director at the Istituto, Pendola wrote a number of treatises on deafness and founded, in 1872, the quarterly journal titled L’Educazione dei Sordomuti (now L’educazione dei Sordi [The Education of the Deaf]). Pendola had been a manual teacher, using sign language, influenced by Sicard, but he modified this teaching method under the influence of his friend Assarotti.

The aim of his new journal was pedagogical, its content directed primarily at teachers of the deaf:

The aim of his new journal was pedagogical, its content directed primarily at teachers of the deaf:

‘The publication was aimed at the analysis of the didactical and pedagogical methods recommended to the teachers of the deaf’ [Esame critico dei mezzi pedagogici e didattici che vengono eventualmente raccomandati o proposti alla scuola dei sordomuti’] (L’Educazione dei Sordomuti, Anno I Serie III, vol. 26, 1903, p. 3). The journal was also aimed at the promotion of the ‘metodo orale’ [‘the oral method’] or oralism, which had been popular in the United States since the 1860s, and had become known to Pendola via the priest Serafino Balestra, who had introduced into Italy the method known as ‘lip reading’.

Oralism – which opposed the use of sign language whilst advocating the use of speech and lip reading in the teaching of the deaf – was now deemed to be the most natural, appropriate and apt method for the social regeneration of the deaf: ‘il metodo orale è, senza contrasto, il più naturale, il più conveniente e il più opportuno per la rigenerazione sociale dei sordomuti’ (Ibid. p.2).

In 1873, a year after the journal was founded, Pendola organised the Congresso internazionale sull’educazione dei sordomuti di Siena [The International Conference for the Education of the Deaf Mutes of Siena]. As with the journal, the conference provided a platform to discuss the advantages of oralism vs manualism, also setting the theoretical basis for the Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf, held in Milan in 1880. The ‘Milan Conference’, as it became known, formally established that oral education was superior to manual education, passing a resolution that banned the use of sign language in schools. As readers of this website and those familiar with sign language will know, it caused much dissent, and is now seen by many as very harmful to the deaf community. Pendola himself was not present, being old and frail, but was proclaimed honorary president (Matson, p.215). Enthused by Oralism in the 1870s, Pendola was was appointed by the government as president of a commission to draw up plans for compulsory education of deaf children (ibid, p.216).

Volume 26 of L’Educazione dei Sordomuti, offers a large number of contributions for those interested in the history of the education of the deaf, including that of a teacher, who, in his article entitled ‘Il vocabolario dei nostri allievi’ [‘the Vocabulary of Our Students’] writes that repetition is fundamental in the teaching of a language, even in the case of deaf people. It also includes a review to Dr. Bezold’s book, published in 1902, on the aetiology of deaf-muteness, and a bibliography of studies on deafness within the context of education.

Pendola would seem to have been highly thought of by those who knew him. He was a professor at the Uninersity of Sienna for thirty years, where, we are told, he fought against the influence of the “popular sensualist school of French materialism” (Matson, p.214). His funeral on the 14th of February, 1883, seemingly held with greater pomp than he might have wished, was attended by much of the populace, and as he had wished, he was buried ‘with the poor, and in the midst of the deaf and dumb, my pupils’ (ibid p.217-8).

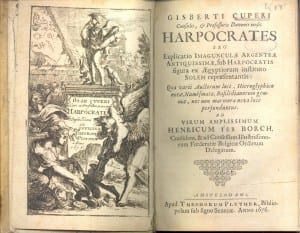

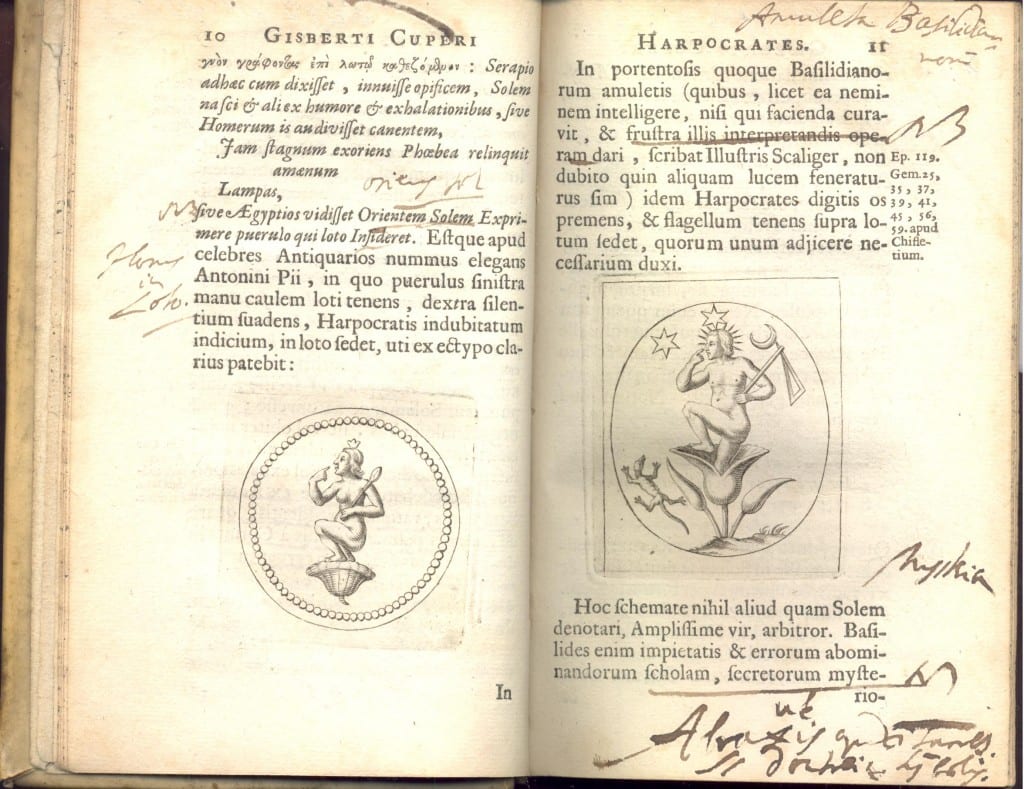

This is one of our copies of Pendola’s book, L’Educazione dei Sordo-muti in Italia, 1855. It appears to be an inscription by the author. His journal, L’Educazione dei Sordi, now available online, continues its publication of research articles, bibliographies and individual experiences in keeping with its pedagogical and didactical purposes.

This is one of our copies of Pendola’s book, L’Educazione dei Sordo-muti in Italia, 1855. It appears to be an inscription by the author. His journal, L’Educazione dei Sordi, now available online, continues its publication of research articles, bibliographies and individual experiences in keeping with its pedagogical and didactical purposes.

We have a long run in the library from the third series, from 1903 to 1925, then picking up again in 1948.

Matson, Mrs. Kate L., Padre Tommaso Pendola, American Annals of the Deaf, 1883, Vol.28 p.213-9 (Matson’s article is mainly the words of Pendola’s friend, Padre Alessandro Toti.

Close

Close