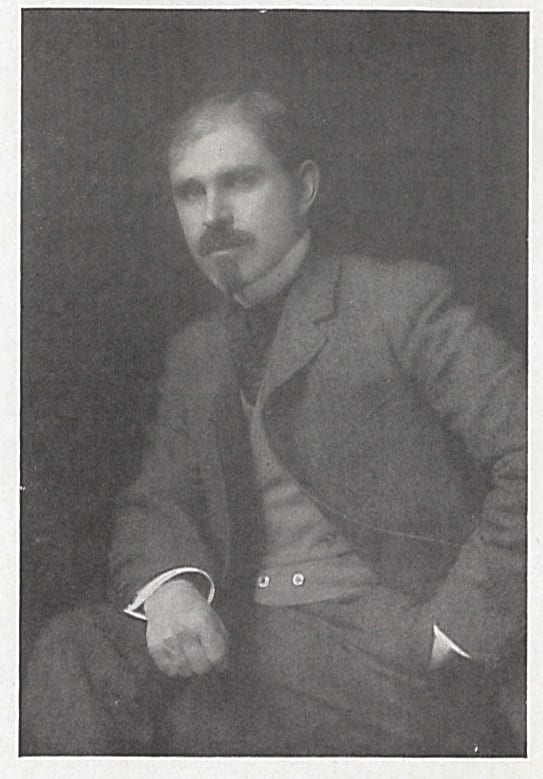

Jean-Jacques Valade-Gabel (1801-79) was a leading proponent of oral education for the deaf who was active in the middle of the nineteenth century. I first came across him through the book of moral tales he wrote, translated into English by Charles Baker of the Yorkshire Institution. His son Andre followed him into teaching the deaf. He taught at the Paris Institution before moving to Bordeaux (American Annals of the Deaf, 1860). Harlan Lane says that he was “fired from Bordeaux for mysterious reasons” (Lane, p.436, note 110). What did he do that was so disgraceful? Since I initially wrote this post I have come across some biographical information on father and son Valade-Gabel.* “Jusqu’en 1850, le nouveau directeur s’appliqua par des leçons constantes à former un personnel capable, dévoué, lorsque brusquement, le 25 juillet 1850, Valade-Gabel fut relevé des ses fonctions et replacé professeur à Paris.” – “Up until 1850, the new director applied himself by constant lectures to forming a capable staff, when suddenly, on July 25th, 1850, Valade-Gabel was relieved of his functions and returned to the position of professor in Paris.” (see Bélanger, 1900). It did not affect his later career it seems.

Jean-Jacques Valade-Gabel (1801-79) was a leading proponent of oral education for the deaf who was active in the middle of the nineteenth century. I first came across him through the book of moral tales he wrote, translated into English by Charles Baker of the Yorkshire Institution. His son Andre followed him into teaching the deaf. He taught at the Paris Institution before moving to Bordeaux (American Annals of the Deaf, 1860). Harlan Lane says that he was “fired from Bordeaux for mysterious reasons” (Lane, p.436, note 110). What did he do that was so disgraceful? Since I initially wrote this post I have come across some biographical information on father and son Valade-Gabel.* “Jusqu’en 1850, le nouveau directeur s’appliqua par des leçons constantes à former un personnel capable, dévoué, lorsque brusquement, le 25 juillet 1850, Valade-Gabel fut relevé des ses fonctions et replacé professeur à Paris.” – “Up until 1850, the new director applied himself by constant lectures to forming a capable staff, when suddenly, on July 25th, 1850, Valade-Gabel was relieved of his functions and returned to the position of professor in Paris.” (see Bélanger, 1900). It did not affect his later career it seems.

Jean-Jacques was born at Sarlat in the Dordogne on the 23rd of September, 1801. He entered the Institution Nationale de Paris on the 8th of September, 1825, as an aspiring professor, which position he attained in 1829. At that time Bébian was deputy Principal. He was a disciple of Pestalozzi (who has been mentioned before on a post).

He taught in Paris from 1826 to 1838, was director of the National Institution at Bordeaux from 1838 till 1850, and later became Government inspector of the schools for the deaf in the 1860s, which must have put him in a powerful position to get his educational views instituted across France (The Association Review, 1902, p.274). Our copy of Méthode à la portée des instituteurs primaires pour enseigner aux sourds-muets la langue française : sans l’intermédiaire du langage des signes (1857) is signed by Valade-Gabel. This was the book that set out his views in full, and in 1875 his method was officially recognised by the Ministry of the Interior (The Association Review, 1904, p.274).

He taught in Paris from 1826 to 1838, was director of the National Institution at Bordeaux from 1838 till 1850, and later became Government inspector of the schools for the deaf in the 1860s, which must have put him in a powerful position to get his educational views instituted across France (The Association Review, 1902, p.274). Our copy of Méthode à la portée des instituteurs primaires pour enseigner aux sourds-muets la langue française : sans l’intermédiaire du langage des signes (1857) is signed by Valade-Gabel. This was the book that set out his views in full, and in 1875 his method was officially recognised by the Ministry of the Interior (The Association Review, 1904, p.274).

We have two copies of the translated Picture Lessons for Boys and Girls, one with the author’s introduction, where he indicates a disdain for signing. It seems he gave emphasis to reading and writing. He says,

The reproach addressed by Jacotot to those who too much distrust the penetration of children, falls directly on such teachers as are in the habit of constantly interposing signs between the deaf and dumb and written language. They become unconsciously genuine stupefying explainers. The more graceful and appropriate are the signs, so much more do they turn the pupils from the attention which must be given to writing, in order to obtain in it a sort of power interpretive of thought. We know in a certain establishment a certain very distinguished master, who, nevertheless, has not succeeded in making a good scholar, for the sole reason that he does not know how properly to teach the deaf-mute to cope with the difficulties of reading. (p.vi)

In The Association Review, they say,

This untiring reformer introduced at the Bordeaux Institution the intuitive method in instruction in language in its written form. He attracted the attention of specialists to his method by annual courses and lectures from 1839 till 1850, and in 1857 published his famous work, “Method for the use of primary teachers for teaching the deaf the French language without the intermediary of the sign language.” This important work was favorably received by the leaders of the French education of the deaf; and in 1875 Valade-Gabel’s method was officially recognized by the Ministry of the Interior. This method which substituted the eye for the ear, employed writing, and abandoned signs as a means for learning language, was adopted either entirely or in conjunction with older methods by the majority of the French schools many years before the Milan Congress. (p.274)

They continue to explain something of his method (p.275): “Valade-Gabel’s method is based on two leading principles: the first, that language shall be taught without either methodical or natural gestures, and the second, that instead of beginning with words, developing and explaining them, each one by itself, the beginning should be made with sentences.”

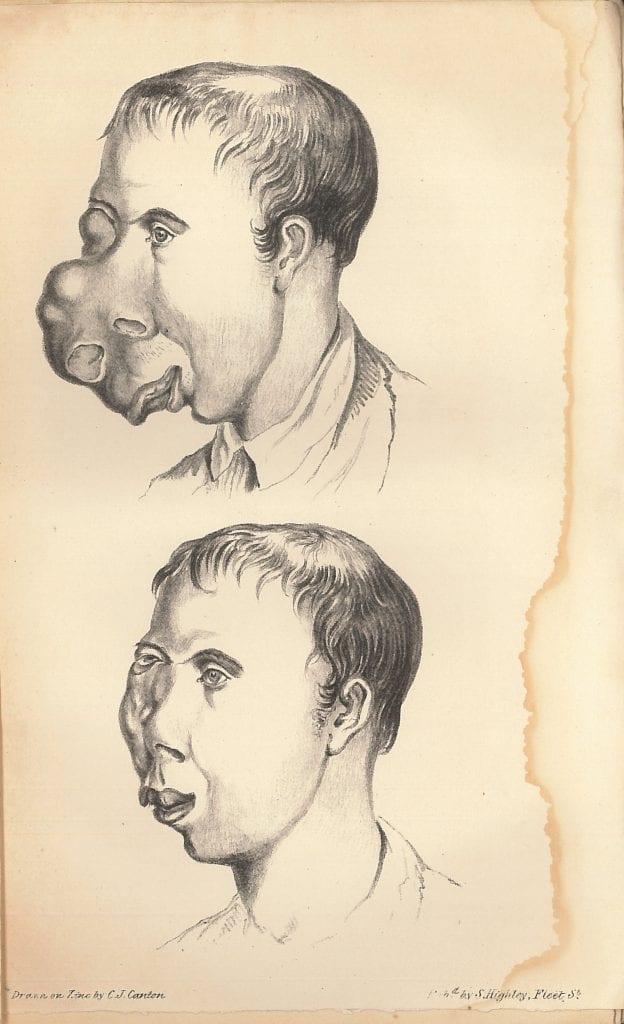

Above are two pages from the Picture Lessons. Note that this last picture below, shows a child – a ‘chatterer,’ – signing to his fellow. “They are chatters when they make any unmeaning or unnecessary signs.”

I think that the poet, Leon Valade, may have been his son, or a relative. Please add a note in the comments if you can provide any additional information about Valade-Gabel.

Arnaud, Sabine, Fashioning a Role for Medicine: Alexandre-Louis-Paul Blanchet and the Care of the Deaf in Mid-nineteenth-century France. Soc Hist Med (2015) 28 (2): 288-307

*Bélanger, Ad., Nos Gravures – J.J. Valade-Gabel, André Valade-Gabel, Revue Générale de L’Enseignement de Sourds-Muets, Vol.2, (5), Novembre 1900 & two plates facing p. 122 & p. 128

Fourth Report of the Institution for the Deaf at Venersborg, Sweden… The Association Review, 1902, Vol.4 p.272–8

Lane, Harlan, When the Mind Hears, a History of the Deaf.

Picture Lessons for Boys and Girls [review] American Annals of the Deaf, 1860 Vol 12, p.191-2

Quartararo, Anne T., The Perils of Assimilation in Modern France: The Deaf Community, Social Status, and Educational Opportunity, 1815-1870. Journal of Social History, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Autumn, 1995), pp. 5-23

Valade-Gabel, J-J., Picture Lessons for Boys and Girls, Translated and adapted by Charles Baker. 1860, London, Wertheim and Macintosh

Valade-Gabel, J-J,, The Institutions for the Deaf and Dumb in France

A picture of Valade-Gabel is on this interesting Danish website

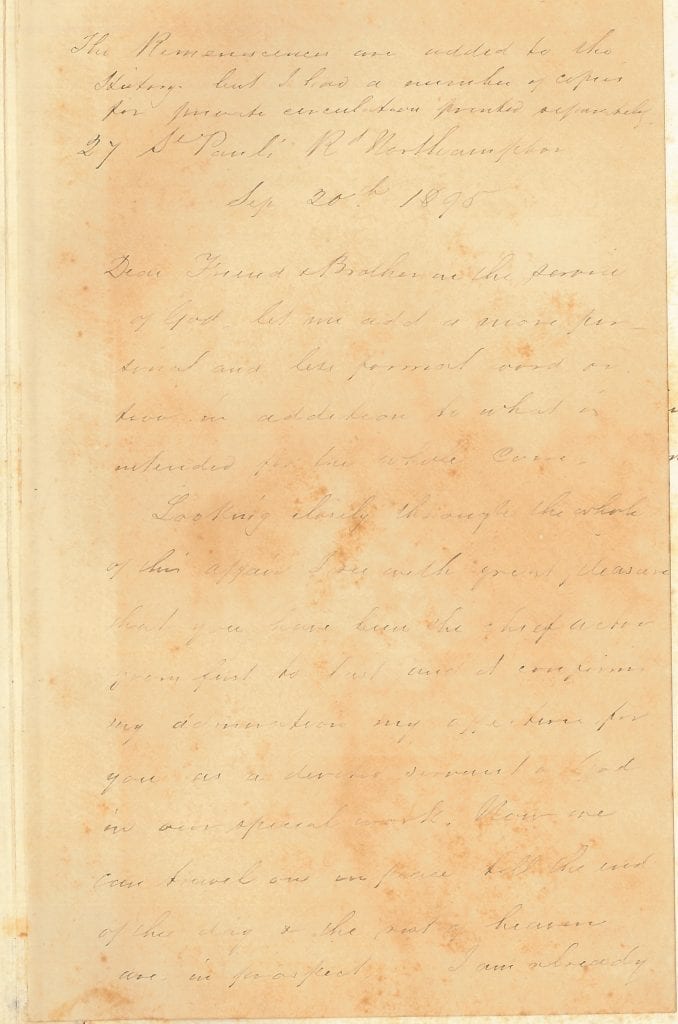

Venetia Marjorie Mabel Baring was a daughter of Francis Denzil Edward Baring, 5th Baron Ashburton. In 1930 she wrote a booklet Deafness and Happiness, our copy being the 1935 reprint. It was published by A.R. Mowbray, who produced religious and devotional books. It is on vey good quality paper. According to the short introduction by “A.F. Bishop of London” who seems to be Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram, she was “afflicted in the heyday of her youth with almost total deafness” (p.iii). Her photographic portrait is in the National Portrai Gallery collection, and a drawing of her is in the Royal Collection.

Venetia Marjorie Mabel Baring was a daughter of Francis Denzil Edward Baring, 5th Baron Ashburton. In 1930 she wrote a booklet Deafness and Happiness, our copy being the 1935 reprint. It was published by A.R. Mowbray, who produced religious and devotional books. It is on vey good quality paper. According to the short introduction by “A.F. Bishop of London” who seems to be Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram, she was “afflicted in the heyday of her youth with almost total deafness” (p.iii). Her photographic portrait is in the National Portrai Gallery collection, and a drawing of her is in the Royal Collection. It is certainly of interest to anyone who is fascinated by attitudes to deafness and how they have or have not changed over the years.

It is certainly of interest to anyone who is fascinated by attitudes to deafness and how they have or have not changed over the years. From the last line of this letter we learn that she was “not born deaf, had acute hearing up to 19, and used no “aids” to nearly 30″ (ibid).

From the last line of this letter we learn that she was “not born deaf, had acute hearing up to 19, and used no “aids” to nearly 30″ (ibid). Close

Close