I have had for the first time the courage to say, “Monsieur, I am growing deaf” – Marie Bashkirtseff, Artist

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 16 November 2018

Maria Konstantinovna Bashkirtseva or Marie Bashkirtseff (1858-1884), was a Ukrainian Russian born artist and diarist. She led a fascinating if brief life, and kept a regular diary from the age of twelve, where she put everything of herself, her hopes, fears, sorrows and joys. Gladstone famously called it “a book without a parallell.”

Maria Konstantinovna Bashkirtseva or Marie Bashkirtseff (1858-1884), was a Ukrainian Russian born artist and diarist. She led a fascinating if brief life, and kept a regular diary from the age of twelve, where she put everything of herself, her hopes, fears, sorrows and joys. Gladstone famously called it “a book without a parallell.”

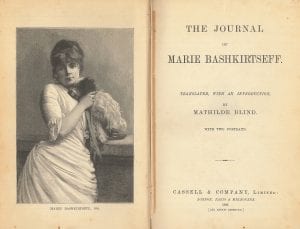

The diaries were originally published by her family in an expurgated version in 1888, which was translated into English by the German born English poet, Mathilde Blind. Marie describes her life, struggles to be accepted in art, and her illness, of which her hearing loss and deafness was a side effect. More details of her life are to be found on the web (see links below) and her portrait paintings are very fine, well worth seeking out. She attended the same Art School in Paris as the British Deaf art student George Annand Mackenzie did some years later, the Académie Julian.

Her experience of losing her hearing will, I believe, be recognized by many in a similar situation. The follow entries date from 1880. At first there is the mishearing –

Saturday, May 8th. — When people talk in a low voice I do not near. This morning when Tony asked me whether I had seen any of Pemgino’s work, I said “No,” without understanding.

And when I was told of it afterwards, I got out of it, but very badly, by saying that indeed I had not seen any of it, and that, on the whole, it was better to admit one’s ignorance. (p.406)

Then she has tinnitus, and has to endure the ignorant behaviour of others –

Thursday, May 13th. — I have such a singing in my ears that I am obliged to make great efforts in order that it may not be noticed.

Oh ! it is horrible. With S___ it is not so bad because I am sitting near him ; and besides, whenever I like, I can tell him that he bores me. The G___s talk loud. At the studio they laugh and tell me that I have become deaf; I look pensive, and I laugh at myself: but it’s horrible. (p.407)

There are times when it improves –

Wednesday, July 21st. — I have commenced my treatment. You are fetched in a closed Sedan chair. A costume of white flannel — drawers and stockings in one — and a hood and cloak ! Then follow a bath, a douche, drinking the waters, and inhaling in succession. I accept everything. This is the last time that I mean to take care of myself, and I shouldn’t do it now but for the fear of becoming deaf. My deafness is much better — nearly gone. (p.416)

Then she is told how serious her condition is –

Friday, September 10th. — … Doctor Fauvel, who sounded me a week ago and found nothing the matter, has sounded me to-day and found that my bronchial tubes are attacked ; his look became . . . grave, affected, and a little confused at not having foreseen the seriousness of the evil ; then followed some of the prescriptions for consumptive persons, cod-liver oil, painting with iodine, hot milk, flannel, &c. &c, and at last he advises going to see Dr. Sée or Dr. Potain, or else to bring them to his house for a consultation. You may imagine what my aunt’s face was like ! I am simply amused ! I have suspected something for a long time ; I have been coughing all the winter, and I cough and choke still.

Besides, the wonder would be if I had nothing the matter ; I should be satisfied to have something serious and be done with it

My aunt is dismayed, and I am triumphant Death does not frighten me; I should not dare to kill myself but I should like to be done with it . . . If you only knew ! . . . . I will not wear flannel nor stain myself with iodine; I am not anxious to get better. I shall have, without that, quite enough health and life for all I shall be able to do in it.

Friday, September 17th. — Yesterday I went again to the doctor to whom I went about my ears, and he admitted that he did not expect to see matters so serious, and that I should never hear so well as formerly. I felt as if struck dead. It is horrible! I am not deaf certainly, but I hear as one sees through a thin veil. For instance, I cannot hear the tick of my alarm-clock, and I may perhaps never hear it again without going close up to it. It is indeed a misfortune. Sometimes in conversation many things escape my hearing. . . . Well, let us thank heaven for not being blind or dumb as yet. (p.422-3)

This was two years before Robert Koch, the founder of modern microbiology, identified the causative agent of ‘consumption’ – Tuberculosis, as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It seems likely that the this was the cause of her deafness, but we cannot be sure. In that year, 1882, she was confronted by the news that her hearing was gone and would not return –

This was two years before Robert Koch, the founder of modern microbiology, identified the causative agent of ‘consumption’ – Tuberculosis, as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It seems likely that the this was the cause of her deafness, but we cannot be sure. In that year, 1882, she was confronted by the news that her hearing was gone and would not return –

Thursday, November 16th. — I have been to a great doctor — a hospital surgeon — incognito and quietly dressed, so that he might not deceive me.

Oh! he is not an amiable man. He has told me very simply I shall never be cured. But my condition may improve in a satisfactory manner, so that it will be a bearable deafness ; it is so already ; it will be more so according to all appearances. But if I do not rigorously follow the treatment he prescribes it will increase. He also directs me to a little doctor who will watch over me for two months, for he has not the time himself to see me twice a week as is necessary.

I have had for the first time the courage to say, “Monsieur, I am growing deaf.” Hitherto I have made use of, ” I do not hear well, my ears are stopped, &c.” This time I dared to say that dreadful thing, and the doctor answered me with the brutality of a surgeon.

I hope that the misfortunes announced by my dreams may be that But let us not busy ourselves in advance with the troubles which God holds in reserve for his humble servant. Just at present I am only half deaf.

However, he says that it will certainly get better. As long as I have my family to watch round me and to come to my assistance with the readiness of affection all goes well, yet …. but alone, in the midst of strangers !

And supposing I have a wicked or indelicate husband ! … If again it had been compensated by some great happiness with which I should have been crowned without deserving it ! But . . . why, then, is it said that God is good, that God is just ?

Why does God cause suffering? If it is He who has created the world, why has He created evil, suffering, and wickedness ?

So then I shall never be cured. It will be bearable ; but there will be a veil betwixt me and the rest of the world. The wind in the branches, the murmur of the water, the rain which falls on the windows . . . words uttered in a low tone … I shall hear nothing of all that ! With the K____ s I did not find myself at fault once ; nor at dinner either ; directly the conversation is just a little animated I have no reason to complain. But at the theatre I do not hear the actors completely ; and with models, in the deep silence, one does not speak loud . . . However . . . without doubt, it had been to a certain decree foreseen. I ought to have become accustomed to it during the last year … I am accustomed to it, but it is terrible all the same.

I am struck in what was the most necessary to me and the most precious. (p.565-6)

She died on October the 31st, 1884, and was buried in the Cimetiere de Passy in Paris, a few weeks before her twenty-sixth birthday.

It is certainly wrong to portray her by her illness alone. She was a dynamic and interesting person, and the tragedy is she did not have the opportunity to show what she might have achieved. I hope some of you will be interested to read her diaries and see her paintings.

Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff, Translated by Mathilde Blind, London 1890

Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff, Translated by Mathilde Blind, London 1890

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marie-Bashkirtseff

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/13916/13916-h/13916-h.htm

Marie Bashkirtseff. Part 2 her later life and diaries

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Bashkirtseff

Marie Bashkirtseff. Part 1 The portraitist and feminist

Gladstone, W. E. (1889). JOURNAL DE MARIE BASHKIRTSEFF. The Nineteenth Century: A Monthly Review, Mar.1877-Dec.1900, 26(152), 602-607. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2630378?accountid=14511

Her paintings:

https://www.ecosia.org/images?q=marie+bashkirtseff

The following looks interesting but I have not seen the article:

Close

Close