The chances are, that unless you are a collector of Victorian Christmas cards, you will never have heard of Helen Marion Burnside (1841-1923), yet in her day her words will have been widely read, for she wrote seasonal greeting verses;

The chances are, that unless you are a collector of Victorian Christmas cards, you will never have heard of Helen Marion Burnside (1841-1923), yet in her day her words will have been widely read, for she wrote seasonal greeting verses;

In honour of the happy time

These girls and boys are brisk as bees,

From peep of day to vesper chime,

Preparing for festivities.

Born on September the 14th, 1841, in Bromley-by-Bow, Middlesex (London), probably at Manor field House, near the beautiful Bromley Hall, perhaps the oldest brick building in London, Helen lost her hearing aged 13 as a result of scarlet fever. Note her birth was in 1841, as Mary Ann Helen – not 1844 as some sources say. I think she cut a few years off her stated age as she got older. She was baptized in St. Leonard’s Church in the 13th of October.

“During my girlhood days,” she once said to the writer, “my greatest desire was to become a musician, but at thirteen years of age a terrible calamity befell me. I became totally deaf as the result of an attack of scarlet fever, and never regained my hearing. Then it was I took to verse writing as another way of making music, for it was the desire to write words for music which, in the first instance, induced me to try the art of rhyming.”*

She was a talented artist, and had a picture exhibited at the Royal Academy when quite young; “before she was nineteen years of age the Royal Academy accepted one of her pictures of fruit and flowers, and, later, a couple of portraits in crayons” (The Strand).

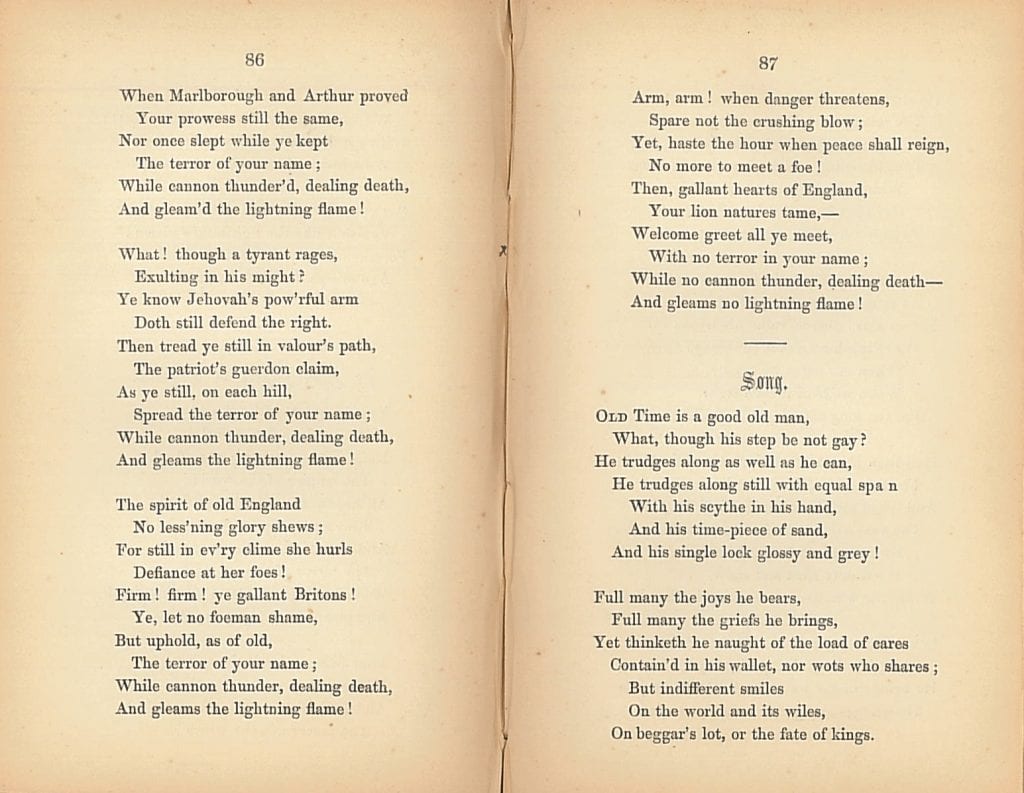

She published many lyrics and poems, and it seems that over six thousand of her verses were put into Christmas cards over the years, as well as 150 of her songs being put to music. This song, advertised in John Bull in 1871, was to music by Miss Maria Lindsay (Mrs M. Worthington Bliss);

It has seemed so long since morning tide,

And I have been left so lone,

Young smiling faces throng’d my side

When the early sunlight shone;

But they grew tired long ago, and I saw them sink to rest,

With folded hands and brows of snow, on the green earth’s mother breast.

Another lyric of hers, The Sprig of May, was put to music by Queen Victoria’s pianist, Jacques Blumenthal in 1883.

She worked as a designer for the Royal School of Art Needlework for nine years, “painting vellum bound books, having obtained a diploma in this branch of art from the World’s Columbian Exhibition.

Marion wrote many children’s books, and contributed many articles to The Girl’s Own Paper, including a story called “The Deaf Girl next door; or Marjory’s life work” which was in the March supplement in 1899, that I have not yet tracked down. I wonder whether she knew Fred Gilby in person, for in a long article in The Girl’s Own Paper for 1897, she wrote an article about the Deaf, talking about The Royal Association in Aid of the Deaf and Dumb, mentioning Ephphatha their magazine, and its editor, MacDonald Cuttell. Writing to her audience of girls, she said, “What they require is to be encouraged to mix , on as equal terms as possible, with hearing persons, not to be set apart and left out in the cold, as if debarred by reason of their affliction from the interests, sympathies, amusements, and occupations of other girls.”

In 1878 she moved in to live with the novelist Rosa Nouchette Carey (1840–1909). She was certainly staying with her a 3 Eton Road, near Chalk Farm, in 1871. It seems probable that they were life long friends as Rosa was also born in Bromley-by-Bow in 1840. Carey left her an annuity when she died.

W.R. Roe wrote of her, in Peeps into the Deaf World,

To her the pleasantest part of her work was that done for children. On leaving the Royal School of Art and Needlework she was for some years engaged in editing for Messrs. Raphael Tuck and Co., and also wrote many stories and verses for children.

She said that the great regret of her life was that she did not become proficient in lip-reading. She had become accustomed to the use of the manual alphabet on the part of her friends, and her life being a busy one, she had neither time nor opportunity to acquire an art which a few years back was regarded as of doubtful value compared to other branches of learning.

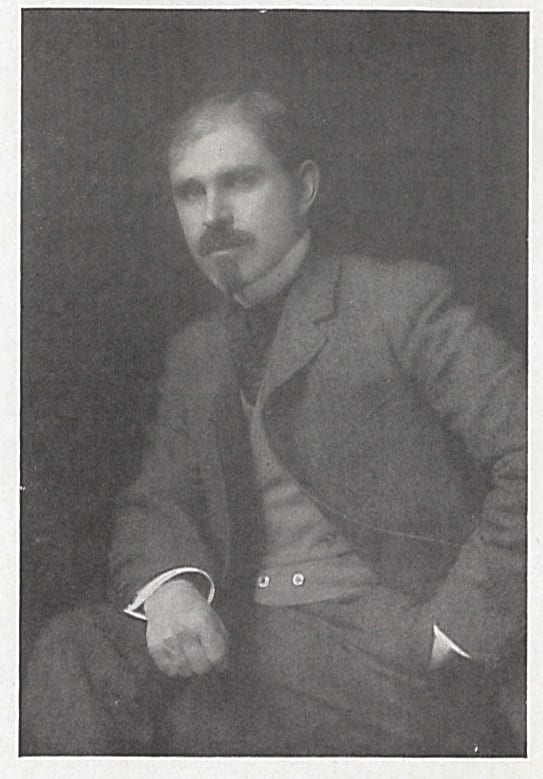

Marion Burnside carried the radiance of her very soul in her face; and she let the world have the benefit of it. (Roe, 1917, p.320)

Helen Marion Burnside died at Updown Hill House, in Windlesham, Surrey, on the 5th of December, 1923.

Exhibited at Royal Academy, 1863; Columbian Exposition (honourable mention), 1895; Society of Lady Artists, 1897; designer to Royal School of Art Needlework, 1880–89; editor to Messrs Raphael Tuck and Co., 1889–95

John Bull (London, England), Saturday, January 28, 1871; pg. 50; Issue 2,616

Burnside, Helen Marion, Help for Deaf Girls. The Girl’s Own Paper (London, England), Saturday, August 14, 1897; pg. 734; Issue 920.

*Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, Volume 4

The Girl’s Own Paper (London, England), Saturday, April 14, 1883; pg. 439; Issue 172

Roe, W.R., Peeps into the Deaf World, 1917 p.319-20

The Strand Magazine, Volume 1, Jan-June 1891 – picture from here

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/terri_klugh/christmas-of-the-past/

http://www.victorianweb.org/mt/dbscott/3.html#lindsay

http://www.ukwhoswho.com/view/article/oupww/whowaswho/U194195, accessed 6 Oct 2017

Census 1851 – Class: HO107; Piece: 1555; Folio: 472; Page: 4; GSU roll: 174787

Census 1861 – (as Mary Ann) Class: RG 9; Piece: 91; Folio: 51; Page: 8; GSU roll: 542572

Census 1871 – Class: RG10; Piece: 194; Folio: 4; Page: 1; GSU roll: 823312

Census 1881 – Class: RG11; Piece: 173; Folio: 65; Page: 22; GSU roll: 1341037

Census 1891 – Class: RG12; Piece: 452; Folio: 86; Page: 38; GSU roll: 6095562

Census 1901 – Class: RG13; Piece: 481; Folio: 170; Page: 17

Census 1911 – Class: RG14; Piece: 5146; Schedule Number: 30

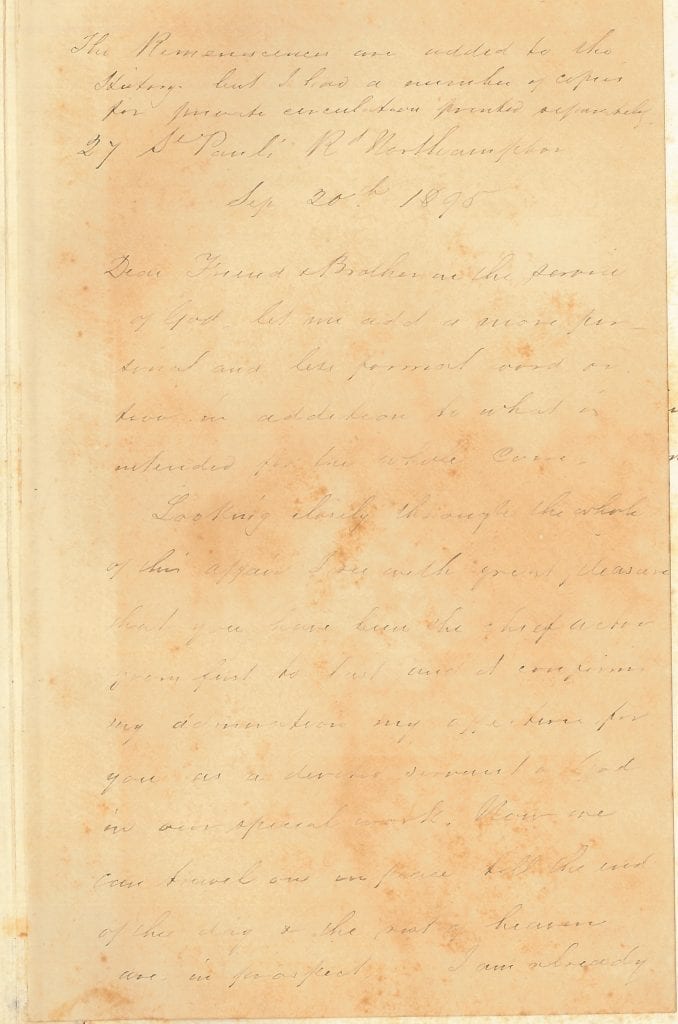

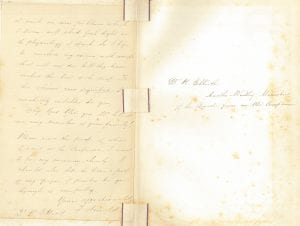

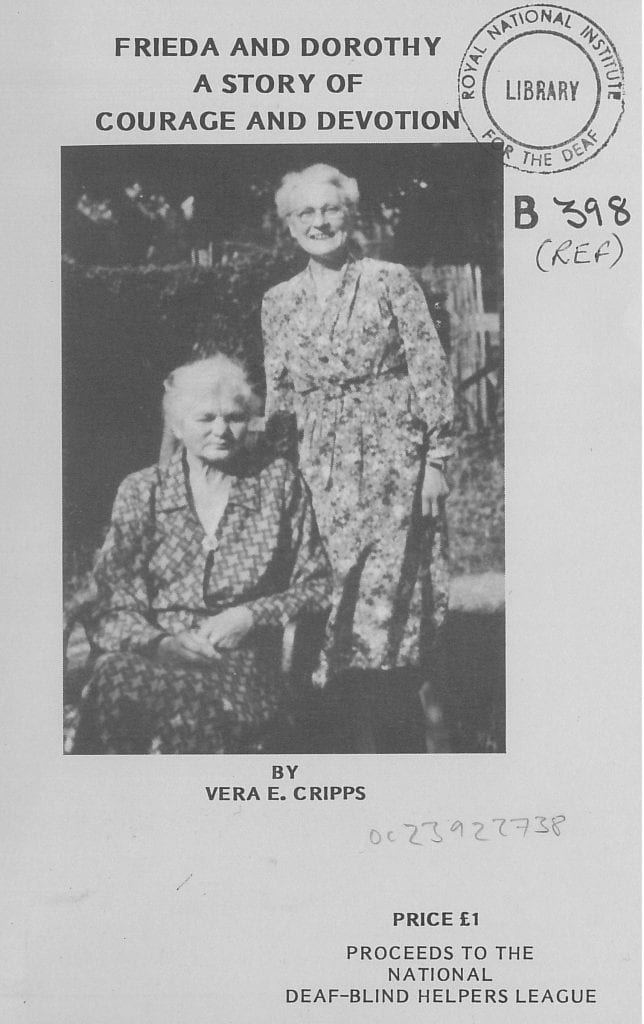

Venetia Marjorie Mabel Baring was a daughter of Francis Denzil Edward Baring, 5th Baron Ashburton. In 1930 she wrote a booklet Deafness and Happiness, our copy being the 1935 reprint. It was published by A.R. Mowbray, who produced religious and devotional books. It is on vey good quality paper. According to the short introduction by “A.F. Bishop of London” who seems to be Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram, she was “afflicted in the heyday of her youth with almost total deafness” (p.iii). Her photographic portrait is in the National Portrai Gallery collection, and a drawing of her is in the Royal Collection.

Venetia Marjorie Mabel Baring was a daughter of Francis Denzil Edward Baring, 5th Baron Ashburton. In 1930 she wrote a booklet Deafness and Happiness, our copy being the 1935 reprint. It was published by A.R. Mowbray, who produced religious and devotional books. It is on vey good quality paper. According to the short introduction by “A.F. Bishop of London” who seems to be Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram, she was “afflicted in the heyday of her youth with almost total deafness” (p.iii). Her photographic portrait is in the National Portrai Gallery collection, and a drawing of her is in the Royal Collection. It is certainly of interest to anyone who is fascinated by attitudes to deafness and how they have or have not changed over the years.

It is certainly of interest to anyone who is fascinated by attitudes to deafness and how they have or have not changed over the years. From the last line of this letter we learn that she was “not born deaf, had acute hearing up to 19, and used no “aids” to nearly 30″ (ibid).

From the last line of this letter we learn that she was “not born deaf, had acute hearing up to 19, and used no “aids” to nearly 30″ (ibid). Close

Close