Interpreter in Court, 1817: The famous case of Jean Campbell, alias Bruce

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 24 January 2014

The case of Jean Campbell should be of great interest to interpreters, Deaf people and students of Scottish law. The story is to be found in Peter Jackson’s Deaf Crime Casebook (1997). Briefly, she was a deaf Glasgwegian woman who was accused of throwing her three year old child into the river Clyde from the Saltmarket Bridge on the 19th of November 1816. I will quote extensively here from the version of the story that appeared in The Dublin Penny Journal some years later (April 1832):

Some time since, in Glasgow, a woman, named Jane Campbell, alias Byrne, [sic] with an infant on her back, was observed on the bridge, leaning her shoulder against the battlements; shortly after, some person heard a heavy fall of something into the river. It was her child – it was drowned! She was apprehended, on suspicion of having thrown it over intentionally. She was deaf and dumb and was brought to trial with strong evidence against her. She had never been taught anything; no one could understand her until Mr. Kinniburgh, the master of the Edinburgh School for the Deaf and Dumb, was sent for – he understood her. She made signs that her child had been supported on her back her cloak, the ends of which she held in her hands, drawn tightly across her breast. Wishing to take some money out of her bosom, she forgot the child for a moment, and incautiously let go her hold of the cloak; the child fell out on the top of the parapet, and rolling over it into the water, was hurried away and drowned. When he made signs to her, that people thought she had done it intentionally, and had thrown the child in; she expressed the utmost abhorrence of the supposition, and the sincerest regret for the child. She had been betrayed and deserted. She expressed the greatest indignation against her betrayer, whom she considered as her husband; but he was unknown, and she could not explain by signs how he could be discovered. Mr. Kinniburgh gave it as his decided opinion, that she was not guilty of the crime imputed to her, and she was accordingly acquitted. Fortunately, this happened in a country where the laws are executed in equity, where the innocent are protected, and even the guilty given the full benefit of investigation; but had it occurred in some foreign clime, where tyranny reigns, and individual rights are unregarded, the rich protected, and the poor despised, and even involuntary ignorance and accidental crime unpitied, she might have suffered a terrific sentence, and the life of a fellow-creature, whose situation excites the most poignant feelings of sympathy, might have been offered up a bloody sacrifice, upon the detested altar of villainy. If there had not been there ‘an interpreter, one among a thousand, to show unto man her uprightness,’ she might have found that ‘none that would be gracious to her,’ and say, ‘deliver her from going down to the pit.’ You shudder at the thought, prevent then the possibility of any Irish deaf and dumb female being exposed to such deception, danger, desertion, widowhood, by promoting the power of; this Institution [Claremont] to educate all that apply.

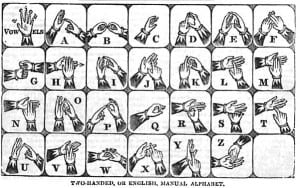

[Left – a sign alphabet from the same issue of the Penny Journal]

[Left – a sign alphabet from the same issue of the Penny Journal]

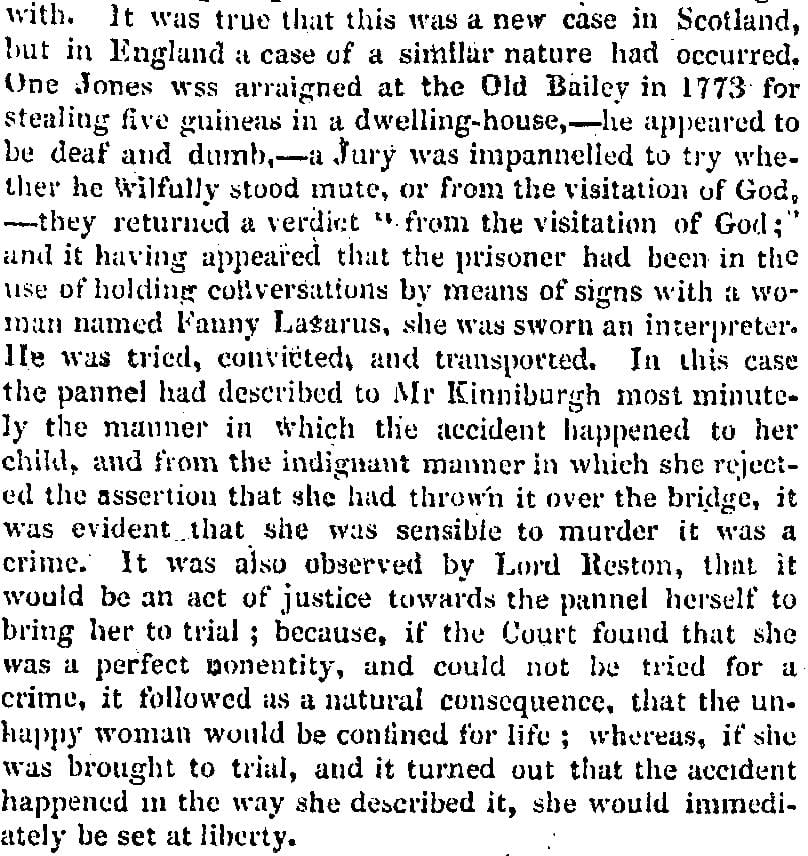

In fact, the pre-trial proceedings are equally as interesting as the trial. Kinniburgh was brought in to try to interpret for the pannel and the court. The ‘pannel’ (a Scottish legal term for the accused) was accordingg to Lord Hermand not fit for trial. Lords Justice Clerk, Gillies, Pitmilly, and Reston were of a different opinion, saying that she was doli capax that is capable of deceit, and having knowledge of right and wrong, quoting a case in England from 1773 (see below) where a jury had to decide if the accused man was wilfully mute or “mute from the visitation of God” and a woman who knew him acted as a sign interpreter. Lord Reston opined that it was in her interests that she should stand trial as if she was found a ‘nonentity’ she would be ‘cont[a]ined for life’ whereas if she were tried and innocent she would be at liberty.

It is important to note that she was not found ‘not guilty’ but ‘not proven’, a verdict in Scottish law where there is evidence against the defendant but insufficient to convict.

After the trial Kinniburgh helped her to travel back to Argyll where her family lived. It would be an interesting project to try to discover what became of her and her surviving children.

Trial of a Deaf amd Dumb Woman for the Murder of her Child – Dublin Penny Journal

Before the trial:

HIGH COURT OF JUSTICIARY.

Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh, Scotland), Thursday, July 3, 1817; Issue 14916

HIGH COURT OF JUSTICIARY.

Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh, Scotland), Saturday, July 19, 1817; Issue 14923

The Trial:

CIRCUIT INTELLIGENCE .

Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh, Scotland), Saturday, September 27, 1817; Issue 14971.

Close

Close