What policies do we need to deliver decarbonisation?

By ucftpdr, on 23 June 2015

Join the conversation: Tweet Paul

Another blog post in this series highlighted that whilst adaptation measures will be required to protect against climate changes that are already ‘locked-in’ due to past emissions, a ‘mitigation-first’ approach is clearly the most desirable pathway given uncertainties about the future, the risks an ‘adaptation-first’ approach may hold, and the health and other co-benefits action to mitigation of GHG emissions would bring. However, the question then arises – what policies and other enabling architecture are needed to pursue such a direction?

By the end of 2013, 66 countries had enacted 487 climate-related laws (or policies of equivalent status, covering both mitigation and adaptation)[i], with a variety of approaches. However, it has become increasingly clear that three key elements are required in any policy mix that hopes to feasibly achieve substantial decarbonisation, in a cost-effective way. The Stern Review first considered these three elements to be ‘carbon pricing’, ‘technology policy’ and the ‘removal of barriers to behaviour change’. Michael Grubb and co-authors developed this idea further in the book Planetary Economics[ii], as illustrated by the figure below.

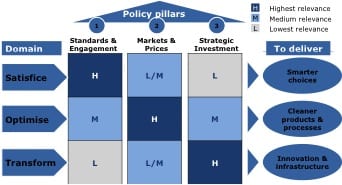

The left-hand side of the diagram illustrates three ‘domains of change’, each of which reflects three distinct spheres of economic decision-making and development – all of which must be addressed. The first is ‘Satisfice’. This domain concerns the short-term, and describes the tendency of individuals and organisations to base decisions on habit, assumptions and ‘rules of thumb’, and reflects the fields of behavioural and organisation economics. The second domain is ‘Optimise’, which describes the ‘rational’ approach to choices that reflect traditional assumptions around market behaviour and corresponding theories of neoclassical and welfare economics. This domain concerns medium-term decision-making. The third domain is ‘Transform’, for which insights from evolutionary and institutional economics describing how complex systems develop over time under the influence of strategic choices made by governments and other influential entities, are most applicable. As might be expected, this domain concerns long-term decision-making.

The three columns in the middle of the figure represent three ‘pillars of policy’: ‘Standards & Engagement’, which operates primarily in the ‘Satisfice’ domain to deliver ‘smarter choices’, ‘Markets & Pricing’, which operates in the ‘Optimise’ domain, harnessing markets to deliver ‘cleaner products and processes’, and ‘Strategic Investment’, which seeks to encourage low-carbon innovation and the deployment of appropriate infrastructure.

Markets & Pricing

Policy instruments that fall under this category – particularly carbon pricing – have received the overwhelming majority of policy-related attention so far. Accordingly, albeit potentially rather surprising to many, carbon pricing mechanisms are relatively widespread – covering around 12% of annual global GHG emissions (see Figure 17 in the Lancet Commission Report for a visualisation of the status of different instruments around the world). Another important aspect in this pillar is the removal of fossil fuel subsidies – the focus of much political attention recently. In 2013, direct subsidies to both fossil fuel producers and consumers totalled around $550 billion[iii]. Whilst this is counterproductive, it is also unfair – around 80% of these subsidies actually benefit the wealthiest 40% of the population[iv]. Taken together, the IMF estimates the ‘total’ subsidies given to fossil fuels (the $550 billion, plus the ‘externalised’ damages a carbon price aims to internalise), reached $4.9 trillion in 2013 (6.5% global GDP), with this value likely to be increasing[v].

Standards & Engagement

‘Standards’ take many forms, however all act to push a market, product or process to higher levels of efficiency (or lower levels of emission intensity), through direct regulation. Such instruments are important where markets and pricing don’t work effectively, in the presence of market failures. A prominent example in the energy efficiency field is that of the ‘landlord-tenant dilemma’. The dilemma occurs when the interests of the landlord and tenants are misaligned. For example, whilst the installation of energy efficiency measures would benefit the energy bill-paying tenant, savings do not accrue to the landlord who therefore has no incentive to bear the cost of installing such measures. Instead, standards can require their installation, or other measures to induce the same effect.

Engaging with institutions, producers and consumers can help overcome a range of issues such as basic awareness and a lack of relevant information, that prevent low-carbon behaviours and investments, even when the economic incentive is there.

Strategic Investment

In order to facilitate the deployment of low-carbon technologies, or to stimulate innovation that instruments under the other two pillars are unlikely to achieve, strategic investment is required. For example, a price on carbon is technologically agnostic, and mainly encourages the adoption of mature low-carbon technologies. To encourage deployment, improvement and cost-reduction of less mature technologies, direct investment is also required (at various stages of the ‘innovation chain’).

Each of the three domains and policy pillars, whilst presented as conceptually distinct, interact through numerous channels. As the figure above illustrates, whilst the impact of each policy pillar is strongest in one domain, each of the pillars of policy have at least some influence on all three domains. As such, all three pillars of policy have an important role in producing a low-carbon global energy system.

[i] Nachmany M, Fankhauser S, Townshend T, et al (2014) The GLOBE climate legislation study: a review of climate legislation study: a review of climate change legislation in 66 countries. London: GLOBE International and the Grantham Research Institute, London School of Economics

[ii] Grubb, M. (2014) Planetary Economics: Energy, Climate Change and the Three Domains of Sustainable Development, London, Routledge

[iii] IEA (2014) World Energy Outlook, Paris, International Energy Agency

[iv] IMF (2010) World Economic Outlook, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund

[v] IMF (2015) How Large are Global Energy Subsidies?, IMF Working Paper WP/15/105, International Monetary Fund

Close

Close