Is there such a thing as ethical and safe disaster research?

By Mhari Gordon, on 29 February 2024

Disaster ethical and risk considerations have received a growing—and needed—interest in the past few years. This has led to a rise in the likes of calls for ‘Disaster-zone Code of Conduct’ (see Profs Gaillard and Peek in Nature) and disaster discipline-specific ethical standards (see Dr Traczykowski in RADIX).

The ‘Box-Ticking’ Exercise

Ethical and risk considerations have long been treated as peripheral to a research project and only reflected upon when applying for ethics and risk assessment approval from a university – with such procedures often viewed as an ‘obstacle’. Common complaints are centred around the time it takes to fill in various forms and providing documentation, as well as the length of the review process. The approval procedures have largely been derived from medical and physical sciences using quantitative methods and analysis. As such, their appropriateness to disaster studies, as well as being treated as a tick-box mentality, has been critiqued by disaster and other social science researchers. There is a need for ethical and risk considerations to be reflected and acted upon throughout the entirety of a project.

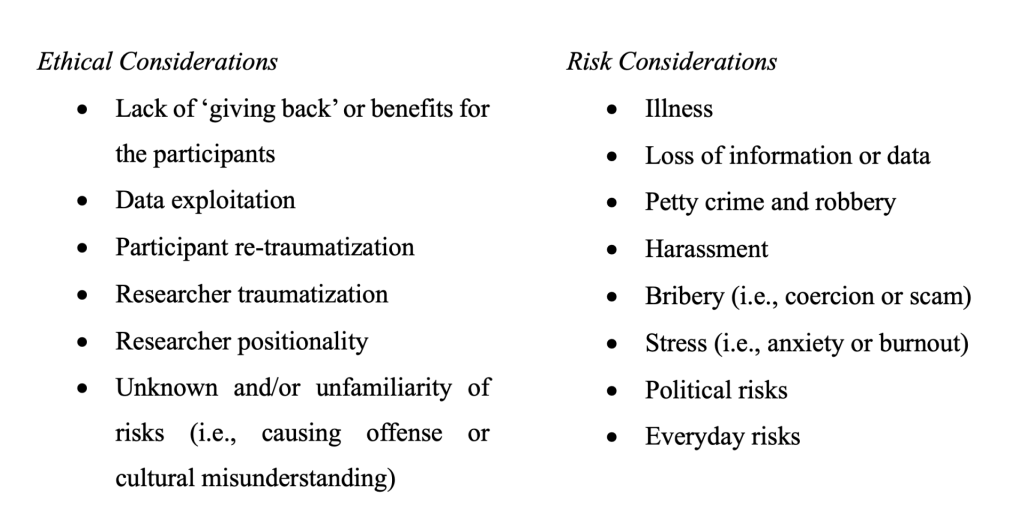

Disaster Ethical and Risk Considerations

Many of the ethical and risk considerations and procedures used in disaster studies have been drawn from lessons and practices in the humanitarian and global health sector. Such sectors tend to operate in different contexts and landscapes than disaster research. A lot of the time, disaster researchers are not working in such controlled spaces or in teams, like in humanitarian responses (see Dr Smirl’s book Spaces of Aid: How Cars, Compounds and Hotels Shape Humanitarianism). Therefore, it is important to reflect and develop ethical and risk considerations which are representative of disaster research.

‘Outsourcing’ of Ethics and Risk

A common mitigation strategy and ‘best practice’ used to overcome certain ethical and risk considerations is to collaborate with local partners or research assistants. For example, having locals conduct surveys or hiring a local person as a driver or translator. Whilst this can contribute great value and legitimacy to a project, it can also (unintentionally) create situations and conditions which may place such individuals in precarious situations (see Mena and Hilhorst’s paper on ethical considerations in disaster and conflict-affected areas or Redfield’s (2012) paper on Médecins Sans Frontières efforts to decolonize). For example, locals being asked by authorities to share information about the project(s) or non-local researchers. As such, this can potentially transfer the onus of ethics and risk from the principal researcher and their institute to their local counterparts.

To assess ethical and risk considerations effectively, research plans and actions should be reviewed and revised during the entirety of the project—with a focus on the relation with others including local people, partners, and organisations/institutions.

Future of ethical and risk considerations in disaster studies

There is a growing recognition within the disaster studies that there is a need to engage in more ethically and risk aware research practices. Some scholars are using and encouraging the use of more reflexive and creative methodologies and methods – stimulating a move away from the historically popular quantitative methods and fully-objective approaches. Multi-media use in combination with more traditional methods, such as interviews, have been increasingly used in disaster research and publications. For example, using playdough or body-mapping workshops and interviews to describe experiences of floods in South Africa (see Emily Ragus) or creating novella-based creative workshops and interviews with Puerto Rican families about their experiences of recovery from Hurricane Maria (see Dr Gemma Sou).

Whilst certain methods may not be new, per-se, the reflexive manner to which they have been applied to disaster studies can be argued to be novel and showing a shift in general approaches. Such approaches will – of course – have their set of ethical and risk considerations, however, these types of approaches have the potential to be more in-tune with such considerations for the researcher, participants, and wider populations. The growing momentum of such approaches is recognised in the likes of an increasing number of signatories to the RADIX Disaster Manifesto and Accord, as well as an upcoming special issue in the popular disaster journal, Disaster Prevention and Management, on ‘Creative, Reflexive, and Critical Methodologies in Disaster Studies’ with a focus on ethical dimensions and power imbalances.

As disasters continue to be experienced and researched globally, it is important that continued efforts are made to further integrate ethical and risk considerations in disaster research. Collaborating and sharing experiences, lessons, and reflections with other disaster researchers and practitioners will be significant in working towards keeping everyone safe in the research of preventing, experiencing, and recovering from disasters.

Mhari Gordon is a PhD student at the UCL Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction. Her research focuses on displaced populations and their experiences of risk, disasters, and warnings, which is funded by the UCL Warning Research Centre. During her PhD, she has been active in other research projects, teaching, and volunteering. Mhari would like to gratefully acknowledge UCL IRDR for funding the expenses to attend the NEEDS 2023 Conference.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author.

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLIRDR

Close

Close