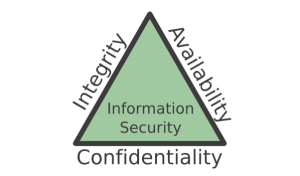

CIA Triad

By Gen Cralev, on 18 August 2017

There is a well-known model within information security called the CIA triad (a.k.a. AIC triad to avoid confusion with the Central Intelligence Agency). The letters stand for Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability. In this blog post I will briefly define each of these concepts and look at some examples of how they are incorporated into the policies, procedures and standards of an organisation.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality refers to data being accessible only by the intended individual or party. The focus of confidentiality is to ensure that data does not reach unauthorised individuals.

Measures to improve confidentiality may include:

- Training

- Sensitive data handling and disposal

- Physical access control

- Storing personal documents in locked cabinets

- Logical access control

- User IDs, passwords and two-factor authentication

- Data encryption

Integrity

Integrity is roughly equivalent to the trustworthiness of data. It involves preventing unauthorised individuals from modifying the data and ensuring the data’s consistency and accuracy over it’s entire life cycle. Specific scenarios may require data integrity but not confidentiality. For example, if you are downloading a piece of software from the Internet, you may wish to ensure that the installation package has not been tampered with by a third party to include malicious code.

Integrity can be incorporated in a number of ways:

- Use of file permissions

- Limit access to read only

- Checksums

- Cryptographic signatures

- Hashing

Availability

Availability simply refers to ensuring that data is available to authorised individuals when required. Data only has value if it is accessible at the required moment. A common form of attack on availability is a Denial of Service (DoS) which prevents authorised individuals from accessing the required data. You may be aware of the recent ransomware attack on UCL. This was a DoS attack as it prevented users from being able to access their own files and requested for a ransom in exchange for reinstating that access.

In order to ensure availability of data, the following measures may be used:

- Regular backups

- Redundancy

- Off-site data centre

- Adequate communication bandwidth

Each aspect of the triad plays an important role in increasing the overall posture of information security in an organisation. However, it can sometimes be difficult to maintain the right balance of confidentiality, integrity and availability. As such, it is important to analyse an organisation’s security requirements and implement appropriate measures accordingly. The following information classification tool has been developed for use at UCL to help classify the level of confidentiality, integrity and availability of data: https://opinio.ucl.ac.uk/s?s=45808. Have a go – the results aren’t saved.

Close

Close