Nostalgia for a field Christmas

By Jolynna Sinanan, on 21 December 2015

Image courtesy of shanzmataz.

It’s the first time I’ve been away from Christmas in Trinidad since I started fieldwork there in 2011 (oh wait, I was home briefly in 2013). December to February is about the slowest three months of the year for working in Trinidad in the lead up to Christmas and the lead up to Carnival, but it’s the best time of the year for an anthropologist whose job it is to hang out with people and do what they do, meet all the people who are important to them and do what they enjoy.

Christmas is a more than a religious festival to many Trinidadians. It’s celebrated by most people in the town, regardless of religious background, as a time to invest in the family and the home as a project. By contrast to living in Melbourne where there a mad rush for shopping for presents and preparing elaborate meals, in addition to these in Trinidad, there’s staying up for most of the night to scrub walls with sugar soap, apply a fresh coat of paint and change curtains. Of course, all of this is done with several relatives dropping in and out between their own home projects so the accompanying food and socialising turns Christmas day into a month of festivities.

When the house is spotless and could pass for a new home with freshly painted walls, the decorations go up. The tree is only the beginning: there are table runners, wall hangings, figurines and plenty of multi-coloured twinkling lights. The many philanthropic organisations in the town collect food and clothes for hampers for older people and those who are less well-off in the community. Home is not only the immediate house that a family lives in, home is also the greater town to be just as cultivated and taken care of.

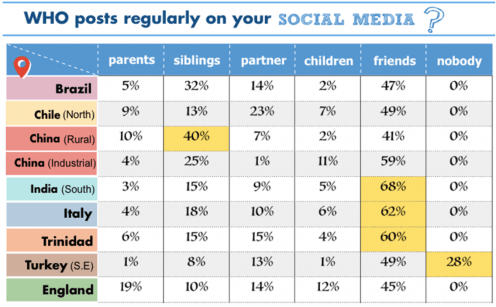

Social media profiles are adorned in the same way in December. From wearing a pair of earrings shaped like Christmas wreaths to playing Santa in the local church or primary school, several profile photos from my fieldsite are of people in Christmas-themed outfits. Prior to Facebook, the circulation of Christmas cards was a time consuming activity, but now instead of sending Hallmark cards people populate the profiles of their loved ones by sharing photo collages with candy-cane or angel embellishments or posting memes.

For those who can’t be home for Christmas, it’s becoming more common to Skype in and sit, propped up in a common space such as in the kitchen or the dining table through a tablet or smartphone over Christmas day, into the evening. I hope this year I might be the disembodied head, beamed in through webcam to enjoy Trini Christmas from afar.

Close

Close