The ‘true meaning’ of Christmas

By Tom McDonald, on 24 December 2012

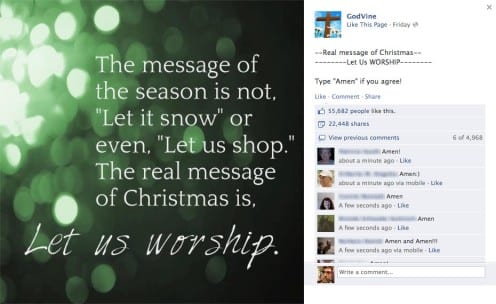

The sacred and the profane double juxtaposed in a Facebook post (Source: GodVine/Unknown)

Complaining about the excessive consumerism of Christmas seems to have become as traditional a past-time as putting up one’s christmas tree, or stuffing the turkey. Christmas and materialism have always seemed somehow opposed to each other, Christmas was supposed to be a celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ, which somehow seemed diluted by the fact that people in Western societies appeared more concerned with rounds of shopping and what appeared to be excessive consumption on gifts, crackers, and shiny sparkly things.

And yet, it cannot be ignored that this is how people actually seem to be concerned with experiencing Christmas. In his essay on the rituals of Christmas giving, James Carrier (1993: 55-74) looked at how people wrapped and gifted presents. He argues that the wrapping of the present was an act that appropriated an otherwise commercial gift, and made it something of the gift-giver’s own. This transformed the gift from a material good to something with a capacity to express love and care between human beings, and thus appropriate for a fundamental aspect of human behaviour: gift exchange (see Mauss 1967).

On the face of it, God and social networking appear to have similarly little in common. The rituals and rites associated with the former are anthropology’s bread-and-butter; whilst the latter is frequently derided as being mundane and of little consequence, inherently unsuitable for anthropological research. And yet, we similarly cannot ignore the fact that this is, for many, an important space where connections with the sacred are contemplated, enacted and observed. And in this sense I do not necessarily mean those events that gain mass-media coverage, such as Pope Benedict’s twitter feed.

Instead, I am more interested in something like religious memes, religious messages that normal people themselves encounter and share through their online networks (see the example above). These are occasions where user-generated religious themed messages might be created, posted or shared. At the moment, I have little idea what these things mean. But when we start our 15 month period of fieldwork researching the effect social networking is having in seven different countries next year, I think it would be reasonable to expect that this phenomena (either from Christianity or other forms of religious expressions) is something we might encounter and want to understand more deeply.

I think anthropology carries with it a pledge: that we take people’s opinions, expressions and beliefs seriously, regardless of what these may be, try to live inside these opinions and understand them for what they are. We do this by living closely with people, and sharing their life for a prolonged period of time. This is not just in order to execute an act of scientific analysis, but is also, first and foremost, a duty that we owe to our research participants.

Whatever your beliefs, I hope you have a very happy Christmas, New Year and holiday period.

References

Carrier, J (1993) The rituals of Christmas giving In: Miller, D (ed.) Unwrapping Christmas. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mauss, M. (1967 [1928]). The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies (I. Cunnison, Trans.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Close

Close