Launching a citizen science paper at the League of European Research Universities

By ucyow3c, on 7 December 2016

Written by Alice Sheppard – Community Manager, UCL ExCiteS

A little over a year ago, many academics and I – not, then, an academic, but a long-time citizen science volunteer – gathered in Zurich for a day of presentations and panels to discuss the idea of creating a set of standards and recommendations for citizen science across and beyond Europe.

Should citizen science have policies and guidelines, or would this be too prescriptive or restrictive? What would ensure that everyone, and science itself, benefitted?

The conference organisers spent the next several months writing a paper of guidelines for researchers and policies for universities wishing to engage in citizen science, which they launched this year’s event in Brussels. I have since started working at UCL, and I was asked to introduce citizen science as a concept, from the perspective of both a volunteer and an academic.

Katrien Maes and Daniel Wyler presented the paper, ‘Citizen science at universities’. Citizen science, an activity where a person not in an academic institution contributes their time to scientific activities, is not new.

Renaissance science was mostly practised by wealthy “gentlemen scientists” (whose wives and other nearby women were often unacknowledged contributors!), and Charles Darwin corresponded with thousands of citizens who recorded aspects of nature around them.

But in the digital age citizen science is undergoing a revival. There is huge new potential for communication between scientists and the public and for data collection and analysis.

Therefore, the paper states, it is important to do three things: citizen science practitioners should collaborate and share best practices; we should create platforms that support a wide variety of citizen science projects, so as to create more public awareness and increase opportunities; and we should not treat citizen scientists simply as agents to get the simple but lengthy tasks done, but to involve them at all stages of the research process, from beginnings to publication.

I was pleased to see advice to use open science and to plan properly for substantial community management. This means not treating citizen scientists as colleagues, taking into account adequate communication with them, tracking not only what they are doing but also their diversity and numbers, and of course properly acknowledging their work.

Citizen science must of course also use proper scientific method and be reviewed just the same as any other science. It still has a reputation among some of being unreliable, though many studies show that this is not the case.

There was also a panel discussion, in which I talked about my experience and my work at UCL. At school and university, I had loved science but been disappointed by two aspects.

“Teaching to the test” at school, where the object is to memorise facts and pass examinations, but not to actually apply these in any meaningful way or to understand how research is done, meant that as an undergraduate I was unequipped to understand research. The students who had had better luck with their education were able to see beyond lectures and to follow more deeply, and knew what to ask and how to go about accessing literature, while the rest of us were continually lost.

The second part of science education that disappointed me was that my degree subject was environmental science – but members of the public were seldom mentioned, much less treated as essential collaborators to solve environmental problems. Lecturers, professors and writers always seemed grand and distant. Of course, if you’re reading this you might well have a job in a university and know that it’s not really the case. But we need to show that it’s not the case.

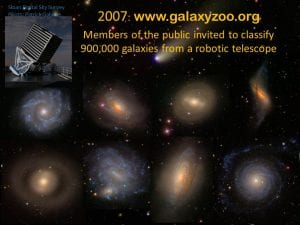

In 2007 I discovered Galaxy Zoo – a citizen science project that invited the public to help classify galaxies – almost by accident and it provided everything I had thus far lacked! I showed the audience a little about how to classify galaxies by shape and recalled the unexpected avalanche of volunteers who did an estimated 3-5 years’ work in 3 weeks.

I described my job moderating the discussion forum, including making sure that everyone had access to knowledge and materials at their own pace. For the first time, I was taking part in original science myself: we discovered new objects and a new class of galaxy.

The best part of Galaxy Zoo was that not all the projects were started by professionals. Amateurs – people whose specialities lay elsewhere, such as in computing – realised that there were areas, such as irregular galaxies, which were not being studied, and that we could do this ourselves. Give people the tools to delve into a database and a place to talk, and that’s what’s needed.

At UCL I am now helping with a project called Do It Together Science, which aims to raise awareness of and participation in citizen science across and beyond Europe, to make citizen science part of science policy, and to link together many different projects to share best. A large collaboration between many specialities – scientists, museums, NGOs and policy specialists – can, we hope, change the way we introduce science to people and get everybody far more involved.

Close

Close