The impact of impacts

By Oli Usher, on 9 February 2015

Two animations, separated by just over half a century. In Walt Disney’s Fantasia, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring is set to a history of the Earth, featuring the dinosaurs gradually dying out in a drought. In 1994, an animated segment from Blue Peter shows the story we’re all with familiar today: a huge asteroid hitting the Earth, causing widespread destruction and an ‘impact winter’ that kills off the dinosaurs’ source of food.

How did we get from the one to the other? This was the question Steve Miller (UCL’s Professor of Science Communication and Planetary Science) sought answers to in his Lunch Hour Lecture, ‘The impact of impacts’ (3 February).

The story begins with a paper in 1980 that pointed out that there was a buried layer of iridium that covered the entire world and was the same age as the last of the dinosaurs. Iridium is an extremely rare element on Earth, but much more common in meteorites.

The research argued that the impact of an asteroid about 10km across could explain both the unexpected iridium and the sudden disappearance of the dinosaurs.

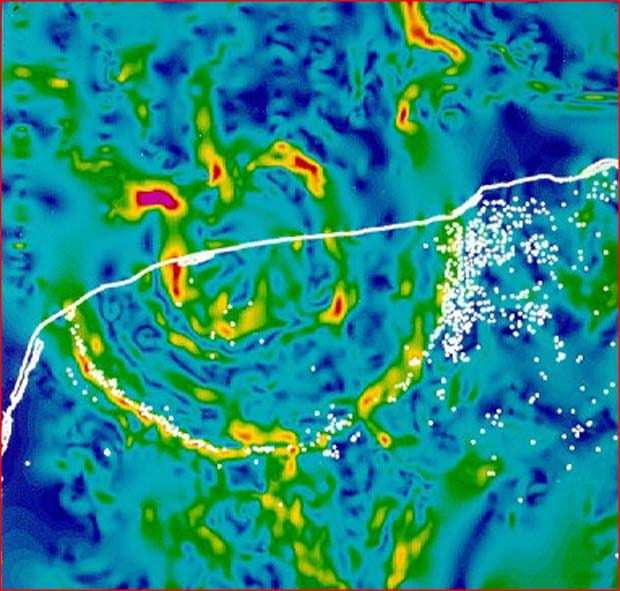

Gravitational map of the Chixculub crater on the Yucatan Peninsula. Credit: Geological Survey of Canada

Scientific debate continued for more than a decade – not least because there was no obvious sign anywhere on Earth of the crater that such an impact must have formed. That changed a decade later when mapping of Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula revealed the faint traces of a 180km-wide crater.

The crater has long since been filled in, but telltale scars remain in the region’s geology – and they point to the impact of an object about 10km across, perfectly in line with the hypothesis of 1980.

By 1991, the debate was largely over, with broad acceptance of the theory that an asteroid impact led to the dinosaurs’ extinction.

But, Miller explained, if you look back through newspaper archives, neither the initial hypothesis nor its later corroboration made much impact when they happened. The asteroid impact theory only broke through into the public consciousness a few years later, thanks to a fortuitous set of coincidences.

First, in 1993, astronomers discovered a comet on a collision course with Jupiter.

Fragments of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, seen by Hubble. Credit: NASA

Second, its predicted impact date fell during the ‘silly season’ of summer, when politicians are on holiday and journalists are desperate for stories to fill their newspapers.

Then, on July 17, 1994, the news event of the year happened.

Not the impact, of course, but the World Cup final. Brazil and Italy ground each other down to a goalless draw, with Brazil eventually prevailing in a penalty shootout. After the celebrations, the fans and the reporters returned home – and the media needed a new story to put in the headlines.

As the final was underway, the other big news event of the year was getting started: the first fragments of the comet were hitting Jupiter, and in the week following Brazil’s triumph, dozens of impacts, vast fireballs and dark Earth-sized clouds of debris animated the planet’s surface.

Grey-brown clouds of dust scar the surface of Jupiter in this Hubble image from 1994. Credit: NASA

This raised the question of whether it might happen to Earth – and in the then-obscure scientific theories about the Yucatan impact and the extinction of the dinosaurs, the media found their answer.

Over the course of 1994, Miller explained, there were more than 80 articles in the UK press about the death of the dinosaurs, and 80% of those mentioned the impact on Jupiter.

The two scientific events – one in palaeontology, and one in planetary science – which on their own might not have made a huge splash, had come together to form a single, huge story that still reverberates to this day.

Today, nobody questions that asteroids are a potential risk, and we’ve even started thinking of how they could be deflected.

So, Miller asked: now that we know what killed the dinosaurs, will we be able to avoid the same fate?

Close

Close