Churchill, his physicists and the nuclear bomb

By Oli Usher, on 22 October 2014

Winston Churchill was not the nuclear naif he has sometimes been made out as. Rather, he was a visionary who grasped the impact of nuclear power and nuclear weapons as early as the 1930s and who lost sleep over nuclear proliferation. But his achievements in the field were as a writer in the 1930s and in his largely forgotten second term as PM in the 1950s, not as Britain’s wartime leader.

This is the argument of Graham Farmelo, who spoke on “Churchill, his nuclear physicists and the bomb” in a public lecture at UCL’s Physics department on 8 October. Farmelo, a physicist and popular science writer, is the author of Churchill’s Bomb: A Hidden History of Science, War and Politics, published last year.

Churchill’s involvement with nuclear research does not begin in May 1940, when became prime minister. Rather, Farmelo said, we need to look at Churchill in the preceding decade.

By 1930, Churchill’s political career was in the doldrums, he had retreated to the backbenches, and any return to ministerial office seemed unlikely. He occupied himself with what he had always done: writing. Churchill had a lucrative sideline in journalism, including articles in mass-market publications like the News of the World, writing on a broad range of topics, including science.

Even before his political career tanked, Churchill had shown a keen interest in science. Among the books he read while posted to India in the army was Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and a primer on physics. And in 1926, while Chancellor of the Exchequer, he had even taken time out from writing the budget to dictate an essay on particle physics to his secretary.

But the 1930s saw Churchill write a number of important contributions to popular science, aided by his friend Frederick Lindemann, the abrasive but politically ambitious director of the Cavendish Lab. Lindemann would later go on to be one of Churchill’s key advisers in government.

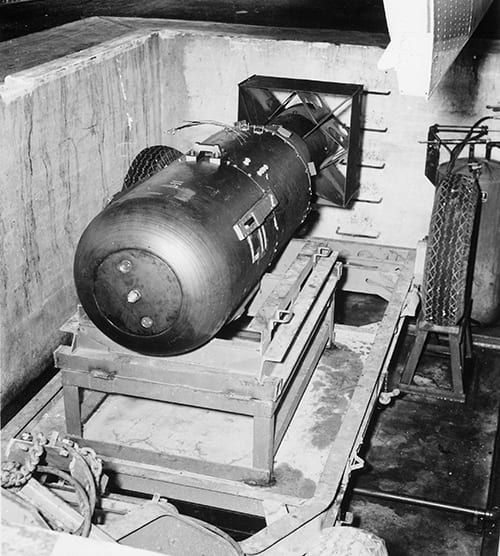

But for all these signs prior to the war that Churchill was alert to the promise of nuclear physics – and arguably even a pioneer – his behaviour during the war was less visionary, Farmelo explained: although the UK under Churchill was the first country to start a nuclear programme (in 1941), a series of poor decisions squandered the country’s lead.

First was the decision to outsource most of the work to industrial giant ICI, a choice with plenty of critics at home. Worse than criticism at home, ICI’s involvement infuriated the Americans, who did not want to cooperate with a project that might give considerable commercial benefit to a foreign private company after the war.

Later, Churchill failed to reply, for seven weeks, to a proposal from President Roosevelt to merge the US and UK projects. In that period, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the US began its own nuclear weapons project and the UK was frozen out.

Then, when Churchill finally managed to get British scientists into the Manhattan project, it was at a huge cost, and entirely on America’s terms – although, Farmelo argued, this at least got the UK its foot in the door, giving expertise to British scientists who led the UK’s post-war nuclear efforts.

Finally, Churchill was not fully alert to the geopolitical implications of the bomb, both in terms of proliferation, and the impact of the Manhattan Project on relations with the USSR. Despite warnings from Nobel laureate Niels Bohr, Churchill and Roosevelt decided to keep Stalin in the dark about the nuclear weapons, which undermined trust between the allies, and didn’t even achieve the desired secrecy, since Stalin’s spies knew about it already.

In 1945, Roosevelt died and Churchill was voted out of office. The momentous decisions in nuclear policy of the late ‘40s were taken by novices. Churchill returned to the political wilderness, still leader of his party, but leading a much-diminished band of Conservative MPs.

In 1951, he staged one last comeback, narrowly winning the general election, and returning to 10 Downing Street at the age of 76. Despite his age and frailty, Farmelo argued that post-war Churchill was in some ways more engaged than he had been during the war. Having lambasted the previous government for failing to develop a nuclear bomb, he discovered that they actually had, in secret, and were just a year away from testing a weapon. And in his final years in office, he took a keen interest in nuclear issues, including détente with the Soviets and curbing nuclear proliferation.

In conclusion, Farmelo argued, there is a case to be made that Churchill was a nuclear visionary – but more as a journalist than as a politician. Given that, it’s surprising that he didn’t take a closer interest during the war, missing out on closer cooperation with the US, and failing to predict the threat of proliferation despite the warnings of an eminent physicist.

Close

Close