Flickering, lost, forgotten: London’s silent picture palaces

By zclef78, on 10 June 2014

Will you come with me to a talkie to-day?

Will you come with me to a talkie to-day?

During my second film event of the UCL Festival of the Arts in two days, I was transported back to the origins of cinema in London’s ‘filmland’. From the bright lights of Leicester Square to the back alleys of Soho, our group of fifteen retraced the steps of early twentieth-century film-goers through Bloomsbury and the West End.

There were a few familiar faces from the previous night’s event Memories of 60s Cinema-Going, all equally curious to discover the hidden stories behind these hitherto innocuous buildings dotted around London.

Led by Dr Chris O’Rourke (UCL Centre for Humanities Interdisciplinary Research Projects) who is researching the social experience of cinema-going in the period of silent film, we began in front of the brutish façade of the Odeon on Tottenham Court Road.

The birth of cinema in London, we were told, was Newman Street, 1894, where private demonstrations of peepshow kinetoscope machines showing a mixture of everyday and spectacular theatrical subjects were captivating 19th century audiences.

From these flickering beginnings, 500 cinemas opened in the London area. Tottenham Court Road alone was home to six including The Majestic Picturedrome, Carlton Cinema and The Court (not the pub) where The Dominion now stands. Somehow they were all commercially successful, just as today’s Starbucks and Costa manage inexplicably to sell enough Americanos to reside next to each other.

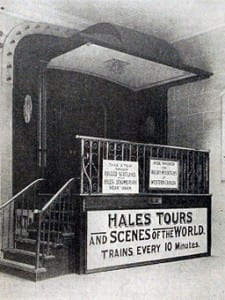

Our next stop on the cinematic circuit: Hale’s Tours of the World (161-166 Oxford Street) where for 6 pence we could travel to Italy and back, or so the postcard claimed. These phantom train rides were a cross between cinema and fairground ride as the auditorium pivoted, tilted and vibrated to vicariously transport the audience to whichever destination was screening that day.

And so it was with a tinge of disappointment that we found ourselves in Soho, not Sicily. Hate’s Cinema, later renamed The Jardin de Paris, operated out of a converted stables–the mangers somewhat undercutting its cosmopolitan aspirations. Chris recaptured the working class experience of cinema in the period in contrast to the well-heeled shoppers on Oxford street with his detailed knowledge and varied anecdotes. “In a 1909 police survey of the best and worst cinemas in London, this was named the worst”, he revealed. The crime film genre and potential for immoral behaviour in the darkened auditorium concerned those who started asking the same questions about the corrupting nature of films in the 1910s as are directed at the video game industry today.

Compare this to the expensive picture palaces on Leicester Square, and we were a world away. After its shiny new £15.3 million makeover, the square was looking pretty good in the afternoon sunshine, In the 1860s it used to be a rubbish dump. Of its variety theatres, The Empire is still going, but sadly the Alhambra’s unusual Moorish architecture was demolished in 1936 and replaced by the Odeon.

By the end of the tour, a fact we were given in the introduction became more and more exemplified in the cityscape. Two thirds of those surveyed in 1927 went to the cinema at least twice a week, whereas today’s cinema-goers only average 2.1 times per year. Even in the 1970s, 21 million tickets were sold weekly (roughly equivalent to half the population). The relative decline of cinema-going today and the changing face of London was exemplified by the gaping hole where the London Astoria used to be.

But there are still hidden cinema treasures to be found around the city. The Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park, once the ‘world’s mightiest wonder theatre’, now the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, still has a full scale model spanish village surrounding the stage: well worth a visit.

Close

Close