Subtitles, Surtitles & Supertitles

By Siobhan Pipa, on 30 May 2014

Subtitled films and programmes used to be the preserve of art house cinemas or specialist TV channels, whilst English speaking versions of popular foreign shows would be commissioned to fill prime-time slots.

And although English speaking recreations are still being commissioned, we are now much more likely to catch the original, in all its subtitled glory, right alongside it.

As a whole we seem to be more accepting of subtitles than ever before, especially if the wave of hugely popular Nordic noir dramas to hit our screens is any indication and in her UCL Festival of the Arts talk ‘Subtitles, Surtitles & Supertitles’, Dr Geraldine Brodie (UCL Translation Studies) has her own theory as to why this is.

Looking at a screenshot from Sky News of the Oscar Pistorius trial, the amount of information on screen is almost overwhelming – news ticker, sports results, date, time, telephone numbers, an option to press the red button, an option to press the green button – all on top of the actual footage and sound of the trial.

Dr Brodie believes it’s our ability to choose where to look and what to focus on when we are visually assaulted with all this information that has made the use of visible translations more mainstream.

It’s this choice of where to focus our attention which links to live performances.

When watching something live, we decide what to focus on – whether it’s the actor speaking, someone lurking in the background or a rather detailed rendition of a tree in the scenery –everything is more interactive for the audience.

At this stage I feel as though I should quickly return to the title of this talk: Subtitles, Surtitles & Supertitles. Before Dr Brodie’s talk I’d never heard of two of these – obviously I know what subtitles are: they’re written displays of dialog on screen, often used to translate foreign language programmes like Borgen or the BBC’s recent adaptation of Jamaica Inn.

It did not, however, click that it is derived from the Latin for below, as in subtitles are often displayed below an image. In contrast supertitles appear above an image and come from the Latin for above and surtitles from the French for “on”.

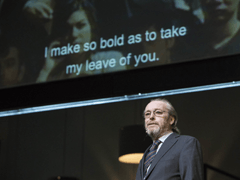

In theatre and opera it is typically “surtitles” or “supertitles” which are used. The translations are projected above the stage or sometimes on to a screen on the seatback in front, purportedly so the audience can take in everything at once.

And with it the very nature of theatre and opera brings its own complications. Unlike pre-recorded television and film each performance is live, different and open to artistic license – most productions won’t be the same two nights in a row.

Here’s a video of Judith Palmer, Surtitler for the Royal Opera House explaining the expertise needed to do this task well:

Typically a theatre will employ a trained musician to follow the performance and display the correct title at the correct time – it’s almost as if the titles themselves are being performed.

It’s here that Dr Brodie makes the interesting point that in live shows, performers are often working with and against surtitles and to combat this producers are adopting increasingly inventive techniques.

It’s difficult to go into too much detail on these techniques when you can’t physically see them in action, just a description of what is happening can’t really give justice to the overall ambience of a performance.

But, one example which is slightly easier to describe is the 2012 Globe to Globe Festival – 37 Shakespeare plays performed in 37 different languages. The plays used a conscious absence of surtitles; short summaries of each scene were projected on to screens either side of the stage.

In cases like this the surtitles almost become a reinvestigation of what is at the core of a production, only what really matters to the audience’s understanding of a scene is used.

As convenor for the Translations Studies MA course, this interaction between translation and language is clearly something close to Dr Brodie’s heart.

Visible translations can add so much to our engagement with performances, something I hadn’t really considered before this talk – the skill and thought process which goes into using them properly is phenomenal.

So next time you happen to be at the opera or watching a foreign play, spare a thought for the Surtitler and offer a round of applause.

Close

Close